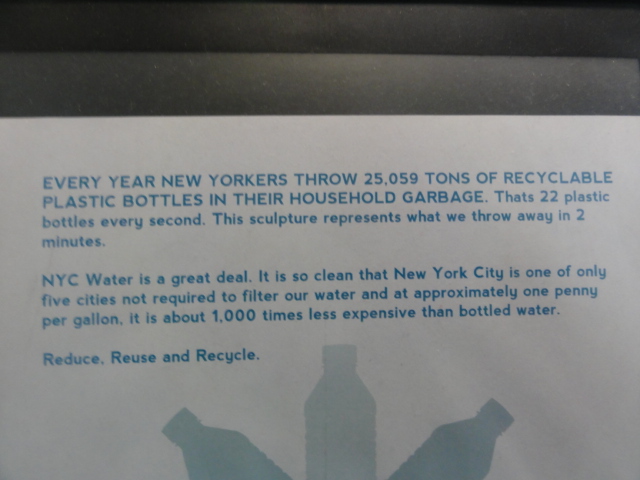

According to Jim Pynn, Superintendent of Newtown Creek’s 52-acre water waste treatment plant, the plant’s star architectural feature is eight futuristic, stainless steel–clad “digester eggs.” Tours of the facility began less than a year ago. Our tour started early in the morning in the new Visitor Center. Once inside, it was hard to hear over the noisy water cascade walkway – a playful, meandering path mimicking a water slide – designed by Brooklyn local Vito Acconci. A sculpture of discarded plastic water bottles hung over the walkway, highlighting the virtues of New York City tap water over bottled water.

Elsewhere in the lobby, signage and models opportunistically taught visitors about water usage and processing – in short, all you’d want to know about your water. By the time we reached the top of the stairs, we’d learned about the history of New York City’s aqueduct system. The two main aqueducts, built in 1842 and 1929, are still in use; water from the Catskills is fed into the city mostly by gravity. A third aqueduct, in construction, is prosaically titled Water Tunnel No. 3. It is the largest construction project in New York’s history. While I give kudos to the city and to Pynn’s entrepreneurial spirit in bringing visibility to a vastly misunderstood yet vital topic, it was disappointing to note that one of the faucets in the women’s bathroom didn’t turn off and was dripping water. A group of over 100 people convened on the second floor to be alternately entertained and informed by Pynn’s hour-long narration of the incredibly technical process of taking waste water — what we flush down our drains and toilets every day in addition to what is carried by the city’s sewers, all 310 million gallons of it — and making it into a relatively benign liquid that is emptied into the Hudson. First, the large debris is gleaned and set aside for dumping into a landfill. Next, smaller particles are strained, squished, cooked, and drained into what they call “sludge,” which is sold as fertilizer. Cooking oil is apparently so common that they have developed a special way of siphoning it off. Pynn pleaded with visitors to relegate cooking oil to the garbage, for solid-waste disposal. The digester eggs mimic the function and temperature of a human stomach, as black, bubbly ooze is fermented by bacteria to create the sludge for further processing. This process stabilizes the sludge by converting most of the organic material into water, carbon dioxide, and methane gas (the gas is then used to power the plant). Visitors got to peer down into the digesters through portholes and see the black stuff percolate.

Bacteria aside, the view from atop the towers was fantastic.

In the end, I felt relieved to learn that my sludge is in such good hands. Pynn has been managing this plant, one of fourteen in NYC alone, for thirty years.

I know that NYC tap water is so clean it is exempt from some of the most stringent filtering requirements. We enjoy nearly 2,000 square miles of pristine watershed in the Catskills and Croton. These lands are even available to the public for exploration and recreation. New Yorkers have reason to be proud of their tap water, and hopefully that will translate into a sense of responsibility to sustain the lands that provide us with so much. What is on the horizon? Pay attention to hydrofracking. The scoop: The Visitor Center at Newtown Creek (not the Newtown Wastewater Treatment Plant) is located at 329 Greenpoint Avenue, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY, 11222 (at the intersection of Greenpoint Avenue and Humboldt Street), and is open to the public from 12–4 p.m. on Fridays only. Tours occur once a month, and reservations are required. Check the Visitor Center calendar for the next scheduled tour. Due to the popularity of these tours and the limited space, they highly recommend reserving a spot in advance. School groups need to fill out an Education Outreach Request Form before requesting a tour of the digester eggs.