Lux in Tenebris, Latin for "Light in Darkness," is a line from Dylan Thomas’s “One Warm Saturday," the last story in “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog.”

“The barman switched on the light. ‘A bit of lux in tenebris.’”

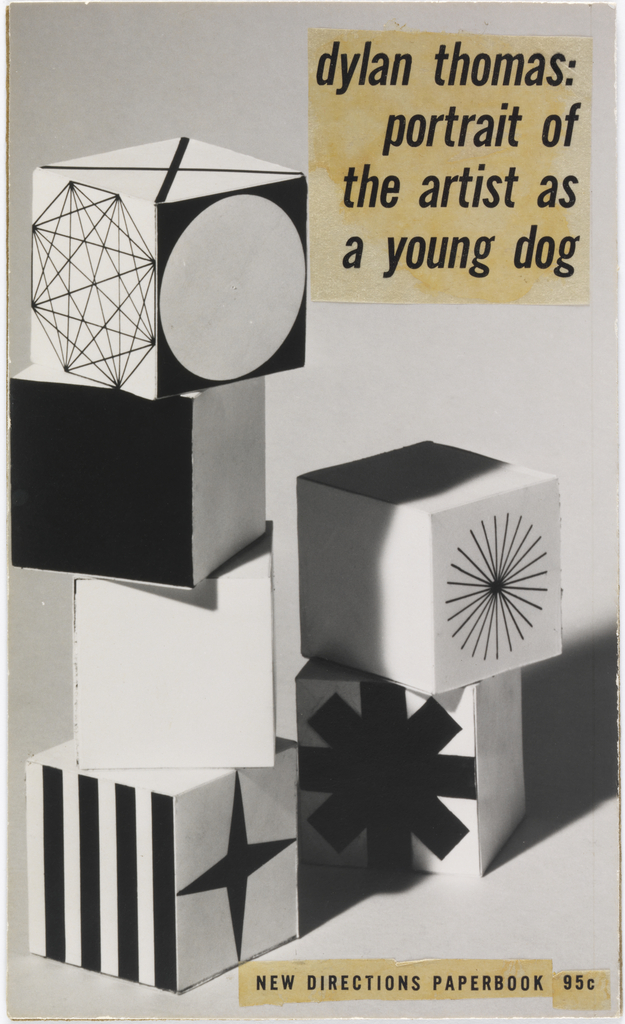

A Latin-quoting barman, a high remark in a lowly setting, light and dark; such correlative contrasts come out in two very different book jacket designs by Alvin Lustig, one selected and one rejected. This book cover maquette is the rejected cover. The image below is part of the accepted cover:

Maquette, Book cover, Dylan Thomas, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, ca. 1953. Alvin Lustig for New Directions Press. Gift of Susan Lustig Peck, 2001-29-2

Lustig writes about his own process when designing a book cover: “Sometimes the symbols are quite obvious and taken from the subject itself. Others are more evasive and attempt to characterize the emotional content of the book.” The two versions portray both ends of this spectrum.

By tracing the fate of an image, much can be learned about taste, marketing strategies of the time, and factors that may forever remain mysterious.

The selected cover, with a photograph of Thomas smoking on the top and a dog smoking on the bottom, is often reproduced, highly visible all over the internet. I grew up seeing it on my parents’ bookshelf.

The other cover, cryptic, Modern, and abstract, has fallen into obscurity.

All because, on a particular day, one highly influential individual (James Laughlin, editor of New Directions) rejected a poetic image in favor of a more direct one. The latter image is so concrete it becomes a witty parody of itself. Why select this one? Certainly, New Directions had published plenty of other abstract book jacket covers.

Was the intention to match Thomas’s shocking title? “Thomas claimed in a letter to Vernon Watkins that he ‘kept the flippant title for—as the publishers advise—money-making reasons.’"

The selected cover design seems far from the prevailing abstract aesthetic of the mid-twentieth century. Characterizing the time is a quote by Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, who, in their letter to the New York Times in 1943, state: “The world of the imagination…is violently opposed to common sense”.

Thomas and Lustig, great artists and thinkers of the earlier half of the twentieth century, might gravitate more towards imagination and abstraction. Abstraction was a mode of expression Lustig was keen on and influenced by, a fan of Miro, Klee, and others whose influence can be gleaned here.

In the rejected cover, Lustig constructed a series of universal yet private symbols in response to Thomas’s stories. These range from stars with varied points, with their accompanying elusive symbolic meanings, to typographic symbols, enlarged and aesthetically pleasing on their own terms.

The other, selected cover is an absurdly concrete illustration of words taken to a comedic extreme, more in keeping with the eventual rejection of Modernism’s subtle mysteries towards a Postmodern, ironic perspective. A smoking dog, humorous and obvious, is a tongue-in-cheek nod to a provocative title with immediate impact.

As a museum educator and artist, one comment frequently asked of me is, “Why is THIS artwork in this museum?” Luckily, Cooper-Hewitt has both in their collection!