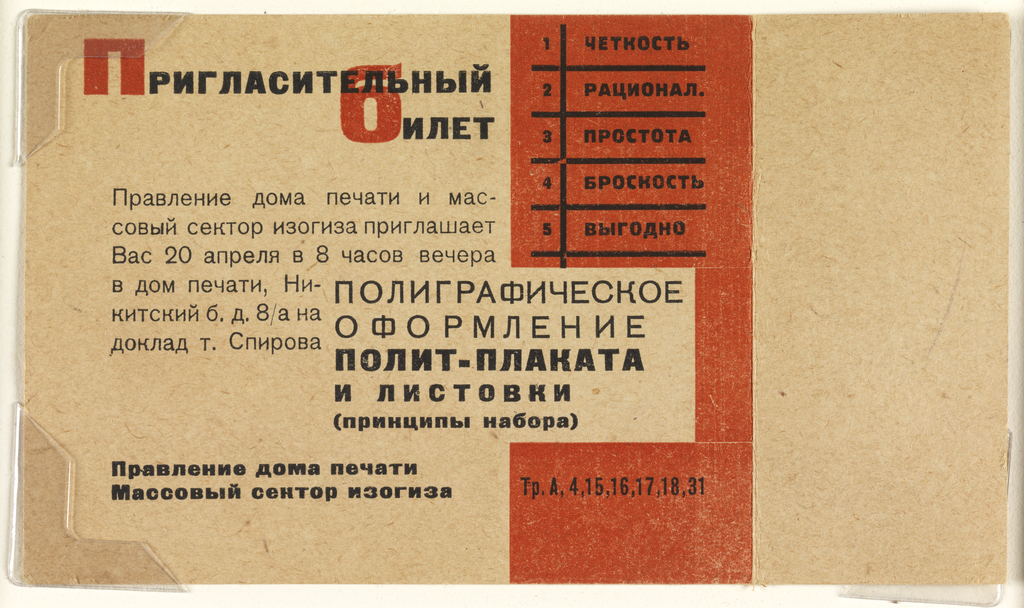

Arresting typography and geometric precision distinguish these Soviet-era tickets, and illustrate the permeation of fine art into daily life in the USSR. The tickets reflect the influence of constructivism, an avant-garde movement characterized by the same angular abstraction evident in these designs. Here, bold blocks of color are poised in asymmetrical balance. As in a constructivist painting, shapes intersect and overlap in a careful composition. This attention to form and balance seems remarkable in a ticket—an object more likely to be crumpled in a pocket or tossed in the trash than exhibited in a museum.

The designers who made these tickets weren’t expecting them to last. In fact, the choice of such a transitory, mundane medium was deliberate; Constructivists were intent on reintegrating art and life. Whereas previous generations of artists studied in exclusive academies and showed their work in elite museums, members of the Russian avant-garde wanted to engage the public with their art. Like the candy wrappers, cigarette packs, and price tags they also created, tickets delivered constructivist design right into the hands of the proletariat.

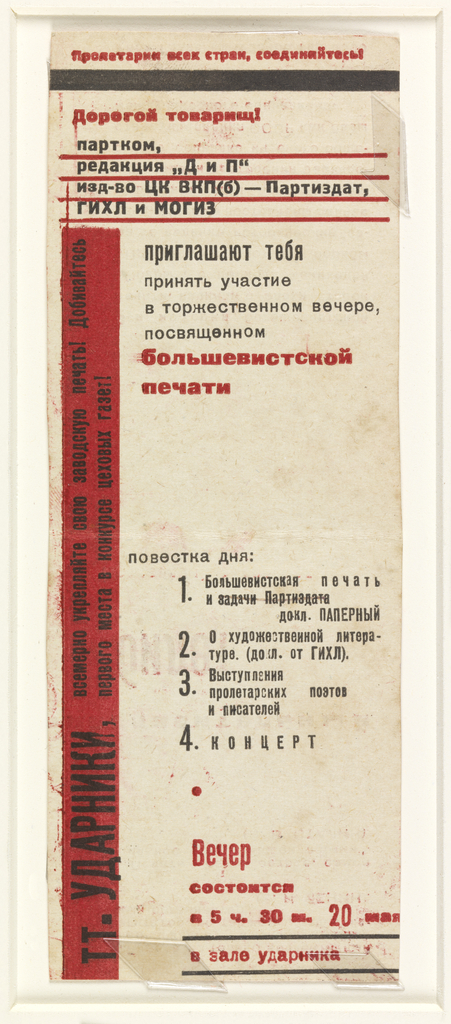

“Dear Comrades!” the ticket below addresses its holders. The tone is friendly and accessible. Just as a gala invitation might be embossed on heavy cardstock to denote exclusivity, these inexpensively printed tickets announce that all are welcome. Like most of the others in this grouping, this is an “invitational ticket” to a symposium on the Bolshevik Press. Sponsored by different divisions of the state publishing house, these events showcased the very printing and design techniques exemplified by the ticket itself.

Constructivists worked closely with the state, using their work to endorse Party initiatives. Like the artists, the Soviet government sought to bring the graphic arts to a largely uneducated population of workers and peasants, to foster shared cultural and political ideologies. Exposure to new strategies of publishing and graphic design was one way of accomplishing this.

Print, Invitation, Moscow Stalin Automobile Plant, Russian, 1930; Letterpress, typography on paper; 9.2 x 6.5 cm (3 5/8 x 2 9/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of Lucy Work Hewitt; 1992-167-10

This ticket lists an agenda for one such event, featuring a statement of publishing objectives, speeches by different proletarian poets and writers, and an evening concert. Incorporating art, education, and entertainment, the events were designed to create well-rounded Soviet citizens.

Despite this shared objective, Constructivist artists had an increasingly strained relationship with the state. By the time these tickets were printed, around 1930, Party officials had grown skeptical of Constructivism’s political efficacy. They were concerned that the style was too abstract and ambiguous to convey a clear civic message, and risked alienating the masses. By 1931, graphic design was being subjected to intensified censorship. Constructivism was banned outright three years later, when Stalin declared Socialist Realism the official state style. A list printed on the ticket seen above outlines the elements of successful graphic design: Balance, Rationality, Simplicity, Catchiness, and Profitability. Though printed in a Constructivist composition, this rubric heralds the formulaic style of Socialist Realism to come.

Virginia McBride is a Peter Krueger curatorial intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She studies art history at Kenyon College.