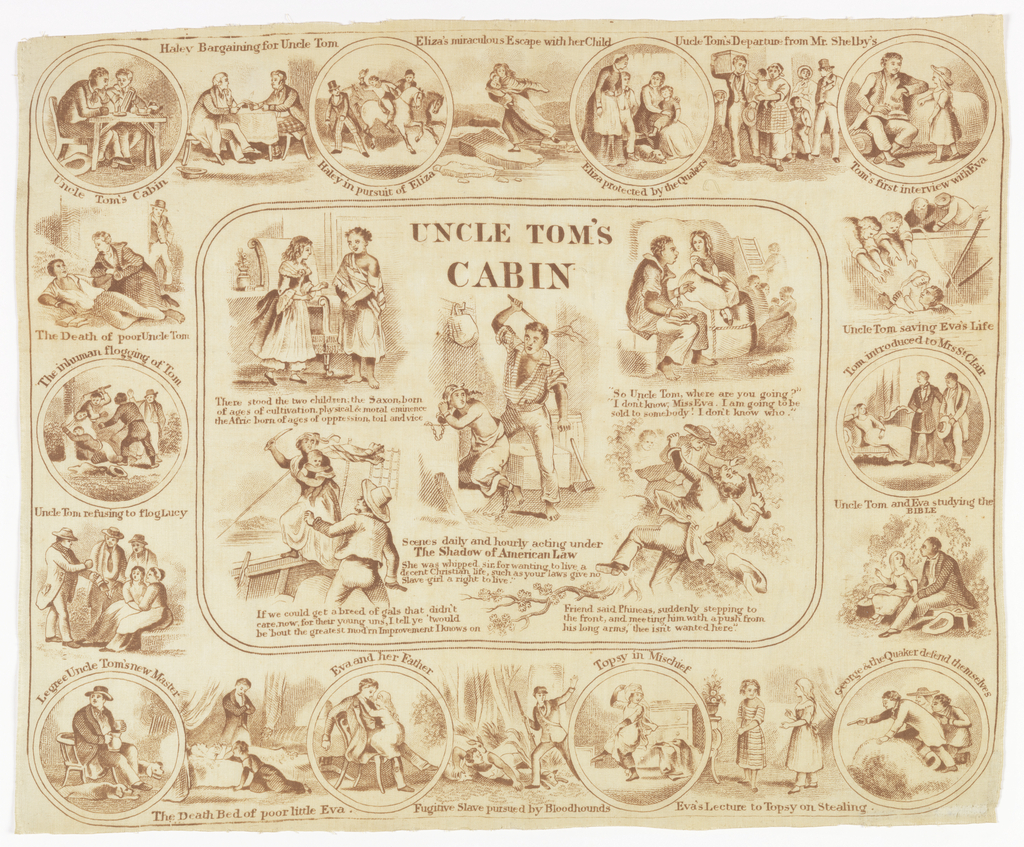

As a graduate student at the Cooper-Hewitt, I experienced a textile collection containing some of the most beautiful and valuable fabrics in the world. But the object I found most intriguing was a mass-produced cotton handkerchief (c.1853) printed with scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Known in its day as a “Tomitude”, the kerchief is a spin-off product from what is considered history’s first blockbuster. Published in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, struck a profound emotional chord with its readers, becoming the bestselling book of the nineteen century after the Bible.

Capitalizing on the deep feelings and unprecedented sales generated by Uncle Tom’s Cabin, marketers created and sold objects for a profit that evoked the emotional experience of the book. These “Tomitudes” were commodities that transformed the drama of the novel into goods that could be part of the reader’s daily lives. ln an era when spin-off products were unheard of, Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a massive cultural industry, spawning a dizzying explosion of Tom-themed merchandise in every imaginable form.

The machine-printed handkerchief provided a fashionable and affordable talisman through which readers could publically demonstrate their sympathy for the cruel plight of Southern slaves. The images on the textile, drawn directly from illustrator Hammatt Billing’s original designs for the novel’s lavishly bound Christmas edition of 1853, can be read as reenacting the sentiment at the heart of Stowe’s storyline.

In this simple object of nineteenth-century material culture, we can see the genesis of today’s mass-market society in which spin-off products from popular narrative works, such as books, movies and video games, spur the production of myriad secondary commodities.

The relationship between the kerchief and the novel reveals the interdependence between texts, images and objects that became the basis for modern consumer culture.

Tomitudes