The image of the painter in his studio is a popular and common visual theme from the early modern period to the present. This particular cartouche, designed by Jacques de Lajoüe, shows a painter with the tools of his trade arranged in the form of a cartouche (a type of an ornamental frame). With the rise of the rococo style in eighteenth century France, cartouches were increasingly used as central ornamental motifs.

Jacques de Lajoüe was painter of architectural fantasies and a prolific designer of ornament prints. He is often referred to as one of the inventors of the rococo style. However, this cartouche presents a composition far removed from the typical rococo iconography of unfurling foliages, shells, flowers, garlands and corals. In the center is a painter, clad in his smock, sitting at an oval canvas with his brush poised against the surface. The oval canvas here stands in for the usual blank center of a cartouche. In his other hand he holds several brushes and a palette. His shadow is reflected on the canvas, reminiscent of Pliny’s tale that Butades, a daughter of a sculptor, drew the outline of her lover’s shadow and thus invented the art of drawing and subsequently the arts.

The painter holds a comically long fire poker in his lap and with it, stokes the fire in the coal oven behind his easel. Near the oven is a child, likely his apprentice, who grinds up pigment in order to make paint. Also depicted in the small rustic studio space are bottles, containers, and materials for frames and mounts. On top of the shed is an owl, likely a reference to Minerva, the patron goddess of the arts. Behind, the rays of the sun shine onto the canvas, imbuing it with metaphorical genius. While the overgrown leaves, the leaping flames from the oven, and the awning of the shed together form an outline of a cartouche; the composition within is closer to François Boucher’s depiction of a painter in his studio, as seen below.

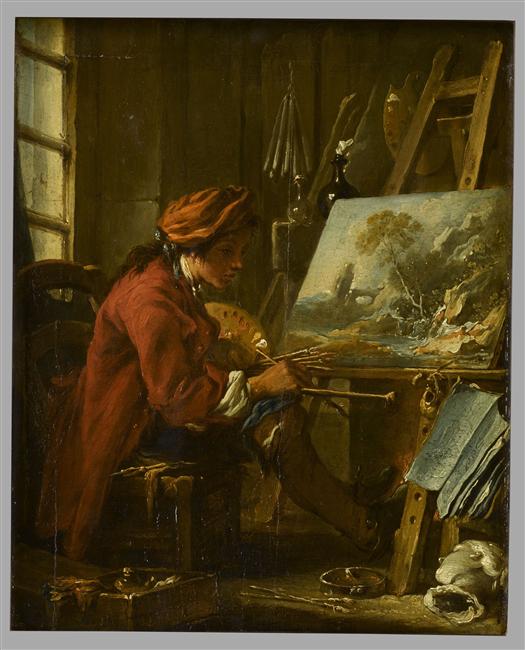

Painting, Painter in his Studio, 18th century, Painted by Francois Boucher (1703-1770); Oil on Panel; Musée du Louvre, Réunion des musées nationaux, Inv. No. MI1024

In this design, then, Lajoüe unites his two professions: an academic painter and a designer of ornament prints. Yet unlike his other designs, this particular print is not intended to be functional. Rather, the design follows the tradition of the emblematic handbook of allegories for decorators and history painters. Lajoüe may be seen to make a visual joke with this design: normally, a painting would be at the center of an ornamental cartouche but here, Lajoüe’s own allegory of painting is transformed into the cartouche itself. Designs such as these reflect an interesting moment in eighteenth century art history when the roles of designers, artisans and academic painters began to collide.

Lajoüe published several designs for cartouches, many of them in the Cooper Hewitt collection. Another example of a fantastical cartouche design is the following one for shipwreck:

Print, Naufrage (Shipwreck), in Livre Nouveau de Douze Morceaux de Fantaisie (New Book of Twelve Works of Fantasy), 18th century; Engraved by Pierre-Alexandre Aveline, Designed by Jacques de Lajoüe; Engraving on laid paper; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, Inv. no. 1921-6-327-24.

Cabelle Ahn is a graduate intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She received her MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art and is currently studying eighteenth century French works on paper at the Bard Graduate Center.