Meet the Hewitts: Part Eleven revealed new discoveries that recently surfaced to enrich our story about the Hewitts. We think June is a perfect time to return to the Hewitt summer estate, Ringwood Manor, to discuss various architects and designers who influenced the gardens and landscape surrounding the property.

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

“A Mysterious Charm”

Meet the Hewitts: Part Five mentioned how Sarah Amelia Hewitt and her daughters participated in the design and care of the gardens and grounds surrounding Ringwood Manor. They were inspired by European gardens they visited, artwork in museums, and information from magazines and pattern books. But others also assisted in creating what House and Garden in 1902 called “the mysterious charm” of the Ringwood Manor gardens.

When the Hewitts first arrived on the property, the surrounding hillsides had been stripped bare of their trees due to more than 100 years of iron mining and charcoal production. Sarah Amelia’s first goal was to recreate the original forests by planting thousands of seedlings. Gifford Pinchot, a visitor to Ringwood and the first Chief of the United States Forest Service, was a leader in promoting conservation of forests. Pinchot married the Hewitt’s great niece, Cornelia Edith Bryce, and visited Ringwood Manor on several occasions. Mrs. Hewitt was so proud of the expanses of trees at Ringwood, she placed deed restrictions on them in 1906, which protect them from any future development that would create the “appearance of an unbroken forest.”

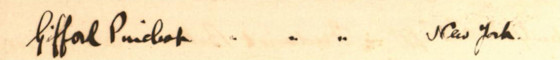

In addition to purchasing seedlings to replant the hillsides, Sarah Amelia ordered numerous flowering fruit and ornamental trees, planting them in rows in an orchard located to the east of the Manor house.

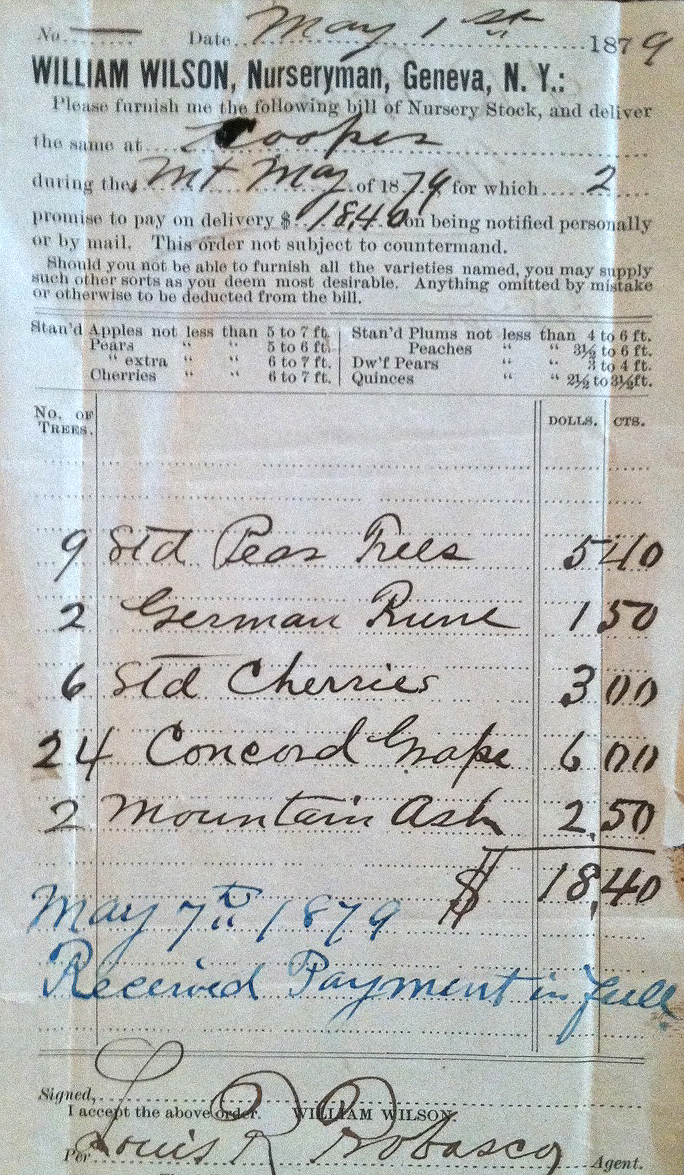

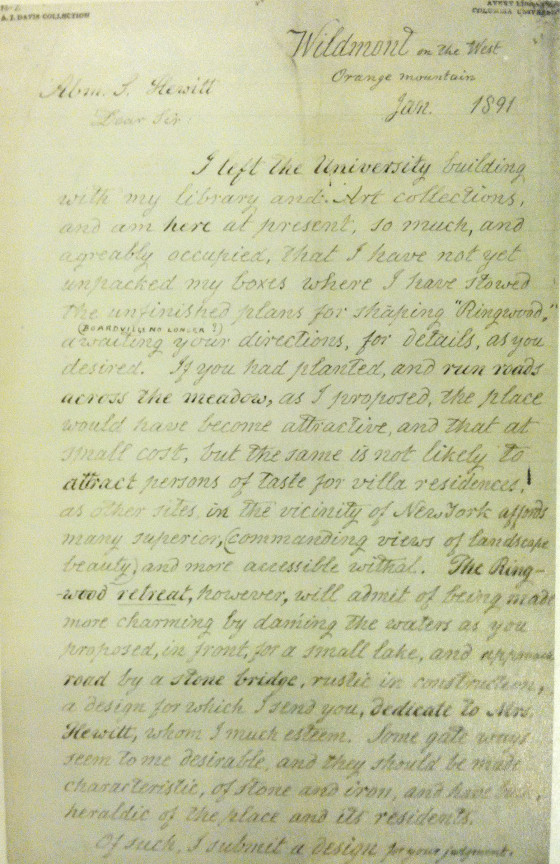

The Hewitt women next focused on the property immediately surrounding the Manor house. During the nineteenth century, it was thought that the garden surrounding a home was as important a feature as the home itself, and, as such, should be complementary in style. Andrew Jackson Davis—America’s leading architect of many varieties of country houses, and a designer of the picturesque landscape—was a proponent of this theory. The letter pictured below, dated 1891, indicates that Davis had previously made recommendations to the Hewitts about the Ringwood property design.

Letter from Andrew Jackson Davis to Abram Hewitt regarding the Ringwood Manor property, ca. 1891. Courtesy of the Avery Architectural Library, Columbia University.

Davis proposed that the “Hewitt retreat” would be made more “charming” by flooding the valley in front of the Manor house to create a water feature, which is now known as “Sally’s Pond.”

An early photograph of the valley in front of Ringwood Manor prior to creating Sally’s Pond, showing the Ringwood River snaking through the field.

Finally, the letter indicates that he designed of one of the stone bridges on the property along with various gated entrances. These landscape “follies” dotted the Ringwood Estate.

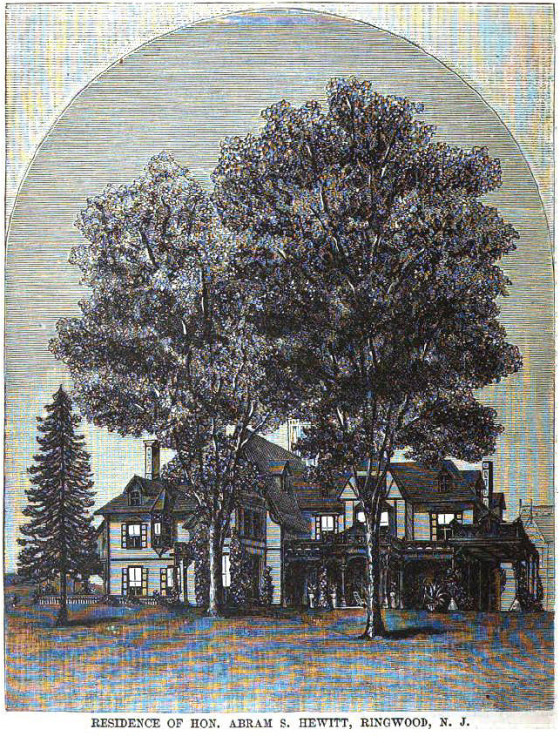

When Davis wrote this letter, Ringwood Manor would have looked similar to the fashionable Victorian country homes that were his signature. The immediate landscape was planted with varieties of trees that were harmonious with the Manor. A written description of the property published in “The Journal of the American Agricultural Association” described the structure and property:

The narrow valley in which [Ringwood Manor] lies is fertile and beautiful. The mansion occupied by Mr. Hewitt stands on an elevation in the midst of a beautiful park of elms and maples, and is further adorned by fine shrubbery, and by a number of acres in a well kept lawn. Here are also a valuable grapery and hot-house, and a large number of fruit trees and choice plants; the verandas, which are very spacious, being filled with rare plants and flowers.

Davis wasn’t the only architect to have an influence on the grounds at Ringwood Manor. Stanford White, of McKim, Mead, and White, designed alterations to the Hewitt residence in New York City and at Ringwood Manor. There is no doubt his neo-classical revival renovation, along with their travels to Europe, influenced the design of the complementary Italian sunken garden to the immediate rear of the Manor.

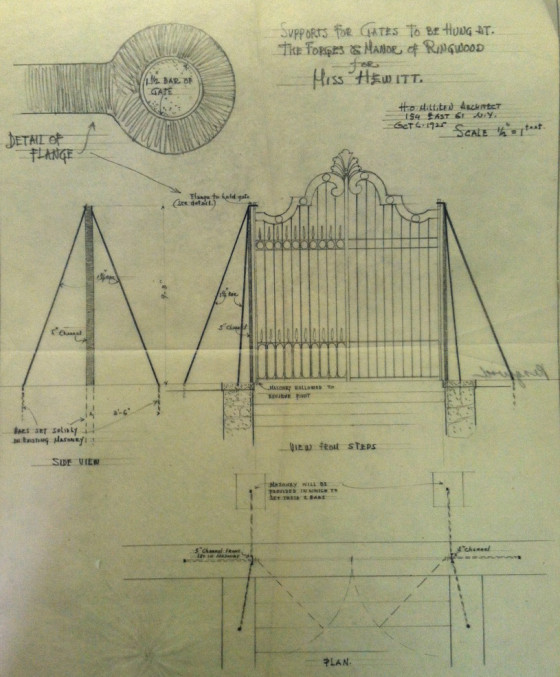

Henry Oothout Milliken—an architect who studied in Paris—was the principal of the New York City architecture firm Milliken and Bevin. He too, specialized in designing town and country homes. Milliken drew the plan below for a gated entrance to one of the Hewitt gardens, but for some reason, the gate was never installed. It now resides in storage in the stables on the property.

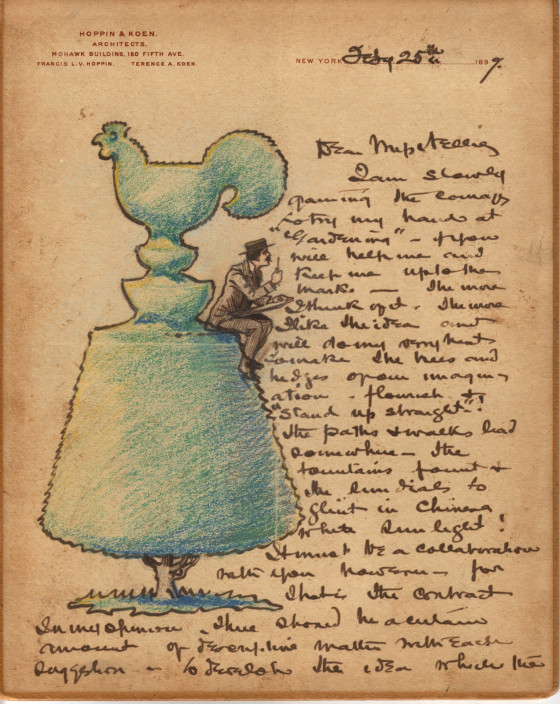

Francis Hoppin—a former employee of McKim, Mead and White before starting his own architectural firm—collaborated with Eleanor Hewitt on a proposed book of landscape design. His fondness for sculpted topiaries can be seen in the various conical, spherical, and “lollipop”-shaped bushes that dotted the Italian sunken garden.

A letter from Francis Hoppin to Miss Nellie Hewitt, discussing a landscape book, with a doodle of a topiary and a self-portrait of Hoppin sitting on top.

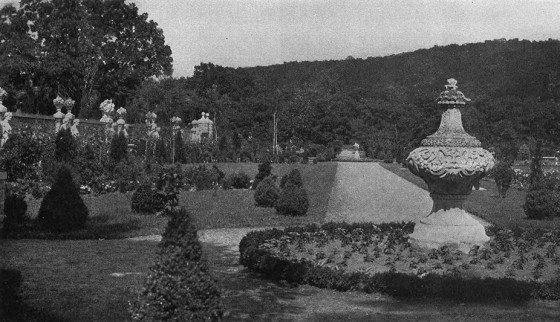

Detailed photograph of the Italian sunken garden showing various shrubs and topiaries sculpted into spheres, cones, and “lollipops.”

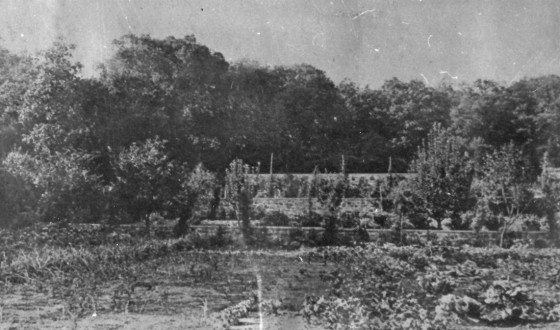

One of the first professional woman landscape architects, Beatrix Jones Farrand, was a niece of Edith Wharton and a friend of the Hewitts. Her name first appears in the Ringwood Manor guest books in 1887 and reappears several times throughout the 1890s. Her influence on the Ringwood gardens can be seen in the distinct separation of garden spaces, creating outdoor “rooms” with terraces that held less formal plantings, inspired by Italian Renaissance gardens. This is very apparent in the tiered vegetable garden, which was full of flowering vegetables, trees, and native roses and flowers. The vegetables from this garden were not only used in the kitchens at Ringwood Manor, but also sent to New York City for use in a small grocery the Hewitt family-owned near Cooper Union.

All of these gardens needed a large quantity of flora to fill their beds with the blooms that visitors would admire. The gardeners at Ringwood Manor would propagate these items in the three greenhouses on the property. While only one of the three greenhouses still stands today, it continues to supply the gardens with flowers.

Sculptures, gates, and various iron objects all were brought to Ringwood Manor to enhance the gardens. Numerous items were brought back with them from their European travels, but many were salvaged architectural features from New York City.

A 15th-century red Verona marble well with Venetian iron was that the Hewitts had installed in their Italian sunken garden.

There are many more objects to be seen in the gardens of Ringwood Manor. The grounds of the National Historic Landmark are open to the public every day of the year, from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Additionally, on Sundays at 2 p.m. from June through October, free guided walking tours of the grounds and gardens are available that highlight the various historic features. Information regarding directions, tours, and events at Ringwood Manor, along with history of the site, can be found by visiting www.ringwoodmanor.org.

Sources:

Duer, Elizabeth. “Ringwood Manor and Its Gardens.” House & Garden Magazine, September, 1902, Vol. II, No. 9: 398–409.

Moulton, Francis D. “The Dairy Stock and Farm of Theo. A. Havemeyer, and its Surroundings.” Journal of the American Agricultural Association, Summer, 1881, Vol. I, Issue 2: 27–36.