This drawing by Giuseppe Barberi is a design for a church. But almost nothing about the structure is typical of 18th-century European churches. The briskly sketched cross that tops the dome announces the Christian nature of the building, but nearly everything below it is of pre-Christian design. The squat, round dome supported by a colonnade is quintessentially classical, and the stepped middle layer of the church resembles the dome of the Roman Pantheon (as well as the dome in Donato Bramante’s early 16th-century plans for St. Peter’s).[1] The overall shape and arrangement of the structure is reminiscent of the 1st century BCE Mausoleum of Augustus. At the center of the church is a triangular pediment on a supporting portico of columns, a hallmark of Greek and Roman temples. The large inscription above the pediment indicates that the church is dedicated to St. George, but the use of “DIVI,” from the Latin for deity, is another strong link with the architecture’s Roman heritage. The four altars in the foreground of the drawing suggest an atmosphere of pagan worship.[2] The overall space takes its cue from imperial fora, which typically featured a large temple and lower walls that enclosed the approach to it.

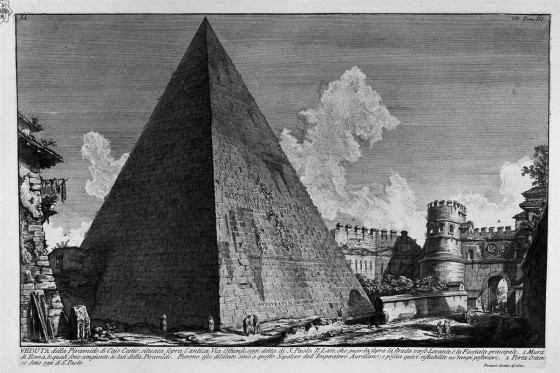

View of the Pyramid of Caius Cestius. The Roman antiquities, t. 3, Plate XL. Etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Public domain, taken from WikiArt Visual Art Encyclopedia.

Even further from standard church design, though not from the architectural landscape of late 18th-century Europe, are the pyramids that flank the passage to the church. Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt launched Europe into full-scale Egyptomania, but interest in ancient Egypt was already high earlier in the century, and architects eagerly incorporated pyramids and other Egyptian elements into their work.[3] Like many 18th-century European representations of pyramids, Barberi may have relied on the 1st-century BCE Roman pyramid of Caius Cestius rather than the pyramids at Giza.[4] The pyramids in this drawing replicate the steeper slope and slimmer shape of the Caius Cestius pyramid in comparison to those in Egypt. There is evidence of Barberi’s design process in the pyramid to the left of the church, which Barberi originally drew closer to the central part of the church.

[1] Crosscurrents: French and Italian Neoclassical Drawings and Prints (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978), 28.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 28-29; Mary E. McKercher, “Egyptomania: Sphinxes, Obelisks, and Scarabs.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/topic/Egyptomania-Sphinxes-Obelisks-and-Scarabs-1688349

[4] Jean-Marcel Humbert, “The Egyptianizing Pyramid from the 18th to the 20th Century,” in Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing Architecture, ed. Jean-Marcel Humbert and C. A. Price (London, U.K.: UCL Press, Institute of Archaeology, 2003), 26.

Vianna Newman is a Peter A. Krueger Intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design. She has a B.A. in Rome and the Renaissance and Italian from Indiana University.