In 1977, in honor of the bicentennial celebrations of a year previous, Cooper Hewitt mounted an exhibition entitled 200 Years of American Architectural Drawing (see more on the exhibition in a special feature on the Architectural League’s website). Curated by David Gebhard and Deborah Nevins, the show and its accompanying publication featured a range of architectural renderings from institutions across America, including those of the Drawings and Prints Department at Cooper Hewitt. Projects designed by the likes of Thomas Jefferson, Calvert Vaux, Julia Morgan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Bernard Maybeck, Mies van der Rohe, Eero Saarinen, and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were all included. Featured drawings ranged from never realized structures to fully completed projects, as curator Gebhard details in the introductory essay of the exhibition catalog. Whether realized or imagined, he suggested, architectural drawings are experienced “through the selective eye of the architect…This is the reorganized world as it should be.” [1]

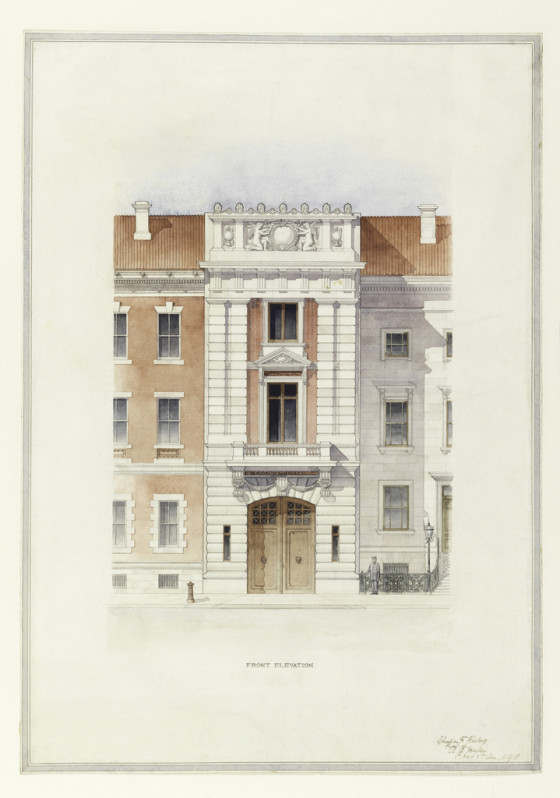

Though many of the architects in the exhibition and publication are well-known to modern-day scholars, little is known about Christian Francis Rosborg, who prepared this drawing for the John David commercial building that dates to April 1, 1940. His career roughly mirrored the extraordinary influence of the Beaux-Arts school’s neoclassical forms early in the 20th century and the eventual rise of International Modernism a few decades later, as evidenced by his drawings. Rosborg (1875-1953) trained under the Beaux-Arts architect Ernest Flagg (1857-1947), who was made famous for designing the Singer building, one of New York’s earliest skyscrapers (which, incidentally, also has the distinction as one of the tallest skyscrapers ever to be dismantled). [2] Rosborg’s design for a fire house, dated to 1905, shows Flagg’s early influence on the young architect’s designs, including the decorative balustrade with an accompanying ornamental relief of characteristic Beaux-Arts figures that marks the roofline.

Drawing, Design for a Fire House: Front Elevation, ca. 1905. Designed by Christian Francis Rosborg. Pen and ink, brush and watercolor on paper. Gift of the Estate of Christian Francis Rosborg,1953-26-3.

A 1912 drawing for an unrealized construction of a new State Department building in Washington, D.C., and a later drawing from 1922 for the entrance to the Banker’s Trust Company in New York are both indicative of Rosborg’s continued interest in the decorative motifs of Neoclassicism.

Drawing, Design for building for the Department of State, 1912. Designed by Christian Francis Rosborg. Pen and black ink, brush and grey wash, graphite on paper. Gift of the Estate of Christian Francis Rosborg. 1953-26-4.

Drawing, Design for Main Entrance Door for the Bankers’ Trust Company, New York, NY, 1922. Designed by Christian Francis Rosborg. Graphite, brush and watercolor, gold tempera on illustration board. Gift of the Estate of Christian Francis Rosborg, 1953-26-11.

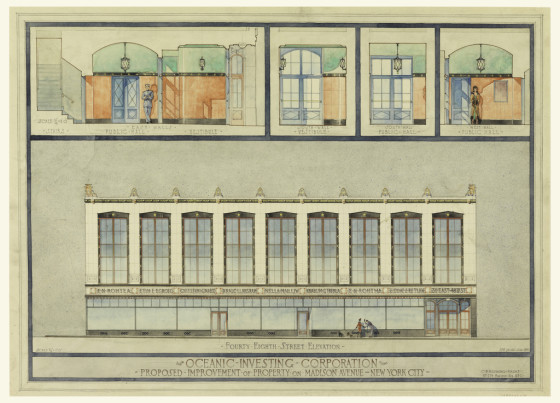

It is surprising, then, to consider the ways that Rosborg’s style evolved over the latter half of his career. A series of drawings from 1933 for the Oceanic Investing Corporation are a direct response to the growing popularity of the Art Moderne style, with its strong emphasis on long horizontal lines, subtle curves, geometric forms and occasional references to nautical motifs.

Drawing, Proposed Improvement of Property on Madison Avenue, New York City: Oceanic Investing Corporation, 1933. Designed by Christian Francis Rosborg. Graphite, brush and watercolor on tracing paper. Gift of the Estate of Christian Francis Rosborg. 1953-26-13

By 1940, the growing influence of both Art Moderne and International Modernism in Rosborg’s work was quite evident. His perspective drawing for the John David department store at 189-191 Broadway illustrates the way the existing architecture was used to emphasize the low-lying angular profile of the new structure. Like any good architect, Rosborg was, as Gebhard writes, drawing “our attention to the symbols and spaces that he feels are significant.” [3] In this case, the long horizontal lines of the minimally decorated facade with large, open street-facing windows offer a dramatic counterpoint to the existing architecture of the area, suggesting Rosborg’s desire to make his modernist creation stand out in a city defined by decorative ironwork and neoclassical ornament. But the drawing is also a significant opportunity to understand the architect’s varied career. The design for the John David building is a dramatic departure from Rosborg’s earliest work as a pupil of Flagg and suggests the international influence of the work of the both American and European modernist architects, among them Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.

The John David department store, which specialized in menswear, was eventually built. But, by 1964, the company fell on hard times and company assets were liquidated. What remains of Rosborg’s building today is a subway entrance and a Payless shoe store, seen below. It is a telling reminder of the ebbs and flows of New York City real estate and the ways that architecture’s original purpose is inevitably modified over time. For the historians among us, it’s a reminder that these drawings are often the only such record that can fix architecture spatially and temporally. “The constructed project exists in time; as a physical object it immediately begins to be modified by nature and by our use of it,” Gebhard writes in the introduction to 200 Years of American Architectural Drawing. “More importantly, our reaction to it continually undergoes a metamorphosis: it cannot, nor does it, remain static.” [4] [5]

Andrew Gardner is a Curatorial Assistant at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

[1] David Gebhard, “Drawings and Intent in American Architecture,” in David Gebhard and Deborah Nevins, 200 Years of American Architectural Drawing, (New York: Whitney Library of Design for the Architectural League of New York and the American Federation of Arts: 1977), 25.

[2] Deborah Nevins, “Christian Francis Rosborg,” in Gebhard and Nevins, 200 Years of American Architectural Drawing, 220.

[3] Ibid, 25.

[4] Ibid.

[5] For further reading on the exhibition entitled 200 Years of American Architectural Drawing, click here.