Liberty and immigration: here are values so intimately tied with the history of the United States and New York in particular, that they seem to permeate one another. The year 1974 was a strenuous one for the US. The recent end of the Vietnam War left open wounds still seething in the minds of millions, as all reeled from the psychological consequences. New York was on the brink of bankruptcy. In the midst of John Lennon’s “Lost Weekend”, Yoko Ono recorded I’m a Witch and Winter Friend as part of her album “A Story,” unreleased until 1992. In the heat of summer, the Watergate Scandal culminated in the Supreme Court’s rejection of President Nixon’s claims of executive privilege, leading to his resignation on August 9th. Only two years earlier, he had personally inaugurated the American Museum of Immigration on Liberty Island. The new museum was housed in the base of the Statue of Liberty.

The same year, Chermayeff and Geismar Associates created this poster for the museum. The design uses the ubiquitous impact of the statue to draw the attention of the viewer. Plastic souvenirs of the famous lady are loosely arranged in three ranks – all different colors, huddled together. Like the generations upon generations of immigrants arriving in New York harbor, anxious for a new future, the clustered visual effect expresses the vocation of the museum: telling the story of those thousands. Turned in every direction, the statuettes exemplify a universal symbol of hope in a new American life for all. The vivid blue background produces a bold, optimistic vision, where sky and ocean seem to mix as one. Detached, white words deliver the message of the poster in a series of small slanted lines, above the upraised torches; almost like flags, fluttering in the wind of Hudson Bay. A white border framing the endless blue ensures the bright colors of the poster aren’t muted if placed on a darker wall or surface.

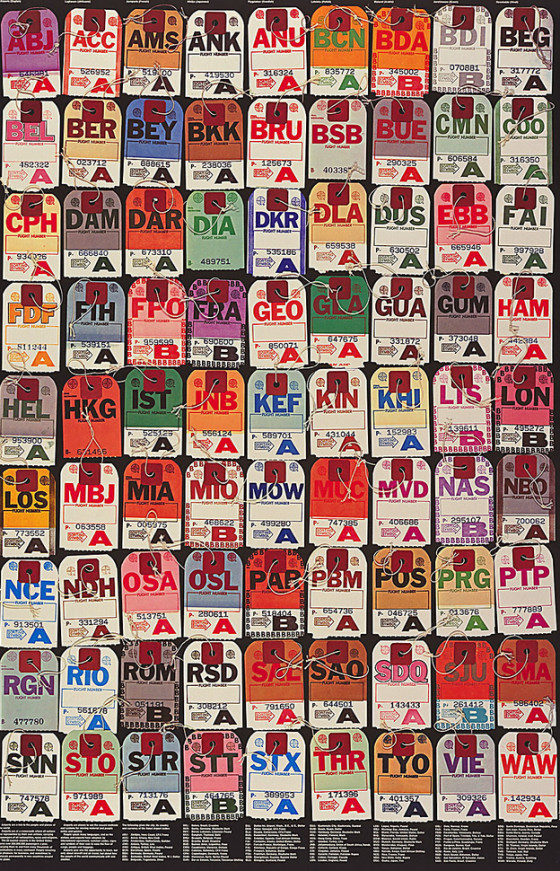

This is not the only poster by Chermayeff and Geismar where repetition and clustering are used to great effect. The design duo named this “the supermarket principle”, whereby the accumulation of a given object – however bland or banal – achieves a greater visual impact. They used this technique in a number of their designs around the same period, famously in 1972 for the Invisible City poster produced for the Aspen Design Conference, also in the Cooper Hewitt collection (see below) [1]. Seemingly simple airport tags are used repeatedly to represent the international scope of the conference, in comparable fashion to the Immigration Museum poster.

Figure 1. Chermayeff and Geismar Associates, The Invisible City, 1972. Created for the International Design Conference in Aspen.

In 1992 the American Museum of Immigration closed its doors after a similar museum opened on Ellis Island, still in operation today. Recently, new galleries have been added to the latter as part of the permanent exhibition [2]. This poster remains as a testament to its defunct predecessor – a bright beacon of hope, created in a time of struggle. Much like the emblematic monument it represents.

Geoffrey Ripert is a graduate curatorial intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Studying at the Ecole du Louvre in Paris, he is currently writing his thesis in Digital Humanities on the Jean Léon Decloux Collection.

[1] See the Object of the Day post on that poster by Ellen Lupton here and the biography of Ivan Chermayeff and Thomas Geismar on the AIGA website here.

[2] See the article by David W. Dunlap in the New York Times via this link.

2 thoughts on “Come, All Ye Weary”

Michael Leddy on August 12, 2015 at 2:33 pm

I love reading Object of the Day posts. But for accuracy: it was really John Lennon’s lost weekend. See, for instance,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/12/arts/12iht-12pang.10978303.html

Geoffrey Ripert on August 12, 2015 at 4:18 pm

Thanks for your input. The wording was equivocal – Hopefully the change rectifies the problem.