Rusticated masonry was first used in the classical world. It is characterized by stones cut with a deliberately rough surface, and wide sunken joints between blocks. The Ancient Romans typically employed coarse stone in public structures such as city walls and aqueducts. However, during the reign of Emperor Claudius (41 – 54 C.E.), rusticated stonework rose in status and was included in more significant architectural elements, such as archways. Among Claudius’ many commissions, the Porta Praenestina best demonstrates the magnificent potential of rusticated stone (fig. 1). The ancient portal initially provided decorative support for two aqueducts, but was repurposed into one of Rome’s city gates. The drums of the columns are very roughly shaped and flare upwards, suggesting an Egyptian influence. The Cooper Hewitt drawing displays a strikingly similar visual rhythm. The Porta Praenestina’s roughly hewn stones remained visible throughout the centuries and eventually captured the interest of Renaissance .

Figure. 1: Porta Maggiore, Rome. 52 A.C.E. Photograph by Alfonso Acocella.

The fifteenth century saw a building boom of patrician residences in Florence. Italian architects studied the classical ruins surrounding them and applied lessons from the ancients to modern structures. Palazzos with partially rusticated stone façades were built for prominent families such as the Medici, Rucellai and Strozzi. These palaces both raised the material’s prestige and established a model for urban residences throughout Europe. While degrees of rustication varied, the stones were typically applied to the lower levels of buildings. These conveyed strength, impregnability, and implied a high economic status worthy of defense. In many cases, however, the rustication was merely a stone cladding economically applied over an existing structure by means of iron rods. Deep grooves between stones cast dark shadows that enhanced the illusion of depth. The sandstone commonly called pietra forte, or “strong stone,” was ideal for this purpose and was readily available in quarries near Florence.

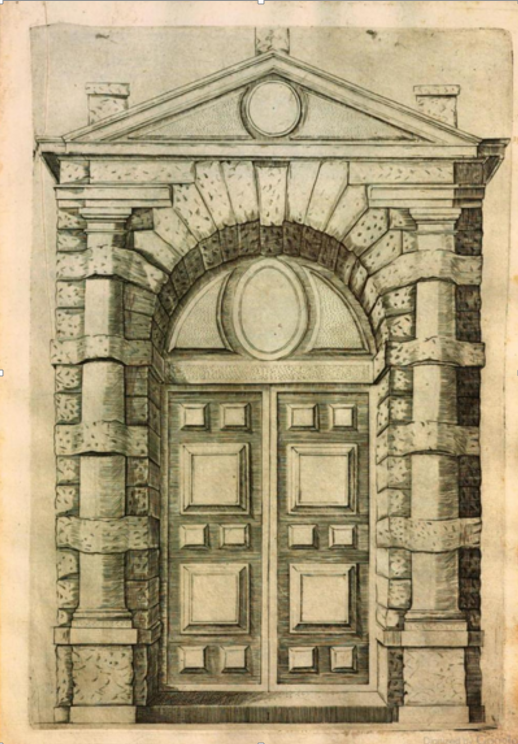

The Cooper Hewitt’s design for a portal includes both a rusticated façade and the Tuscan order of architecture, a combination relatively rare among architectural drawings produced in Italy during the sixteenth century. Rustication was particularly associated with the simple Doric and Tuscan orders, a view first established by the first century C.E. architect Vitruvius. Visible in the in the Cooper Hewitt drawing is the undecorated Tuscan entablature, smooth capital, and rounded base. A focused interest in the Tuscan style arose in the mid-sixteenth century, with several publications and building programs seeking to establish the nature of the order, which had previously been largely omitted from study. Most significant among these was Sebastiano Serlio’s Regole Generali Di Architetura Sopra Le Cinque Maniere De Gli Edifici (Fourth Book of Architecture), published in Venice in 1537. Serlio developed a theory of architectural decorum, in which each order was associated with a particular type of building or patron. . Like rustication, they symbolized strength and protection, and were considered suitable for important buildings, such as a consul’s palace.

Fourteen years later, while working for King Francis I in France, Serlio published a series of fantastic designs for gates. Two of these combine the Tuscan order with rustication (fig. 2). It is clear that the unknown designer of the Cooper Hewitt drawing was familiar with Serlio’s publication; the projecting ashlars (cut stones) partway up the arch, and the three blocks rising above the pediment closely resemble Serlio’s designs. The publication was circulated in France and Italy, and was later republished in the Netherlands, helping to promote Serlio’s theories. In the following century, rusticated stonework rose in popularity, and could be found in palace design throughout Europe.

Fig. 2. Serlio, Sebastiano. Extraordinario Libro Di Architettura Di Sebastiano Serlio: Nel Quale Si Dimostrano Trenta Porte Di Opera Rustica Mista Con Diuersi Ordini: Et Venti Di Opera Dilicata Di Diuerse Specie Con La Scrittura Dauanti, Che Narra Il Tutto. In Lione: Per Giovan di Tournes, 1551.

Rebekah Pollock is a design historian specializing in eighteenth-century print culture and European ceramics. She has a Masters in the History of Decorative Arts and Design from Parsons The New School for Design / Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.