If anyone has come to know seminal avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson, they will have witnessed the autodidact hard at work sketching. Whether backstage at a major European opera house or cramped into an economy-class plane seat—flying over the Alps to simulate the intensity of a Wagner aria—he always garners silence when drawing. When at Watermill, his Long Island-based performance laboratory and summer residence, Wilson can be found surrounded by a swarm of dramaturgs, set designers, choreographers and students eager to watch the grandmaster drafting new concepts. With stacks of blank paper and mechanical pencils, his loose freehand sketches shapes and figures, but also moods and light voids through cross-hatching, smudging, and eraser marks. Visitors are invited to stand on chairs and watch him at work, almost as if staged in one of his productions.

Wilson’s use of drawing as a preliminary tool is conditioned by his mobility—in a given week, he travels on as many as twelve planes to work on simultaneous projects around the world.[1] “Philip Glass always says that I think by drawing,” he explained in a 2014 interview with Frame magazine. “Very often when I’m thinking of something, I take a pencil and start drawing to see what that ‘something’ could be. Whether it’s the direction of a light or an angle, drawing is the only way I can understand space.”[2] Wilson’s method derives from his architectural and painting training.[3] Productions like his acclaimed Einstein on the Beach were mounted on structures notated like number diagrams. This approach is also evident in five decades of set design drawings, which Wilson created in lieu of traditional script formats.[4] A series of sketches from Cooper Hewitt’s collection, created for a May 1990 production of Shakespeare’s King Lear at the Schauspiel Frankfurt, showcase the director’s process.[5]

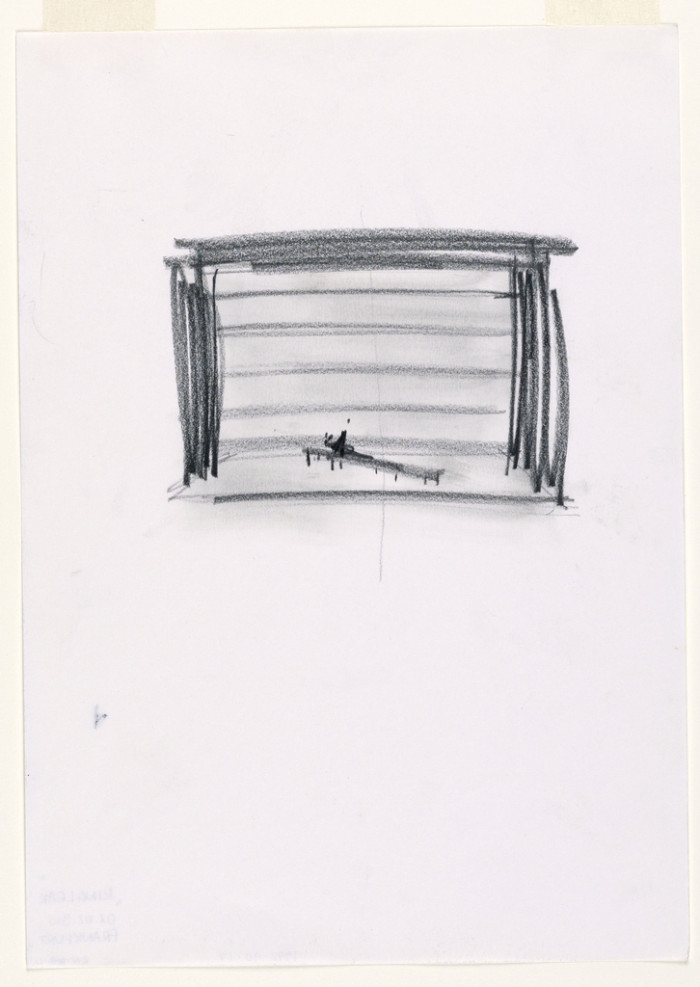

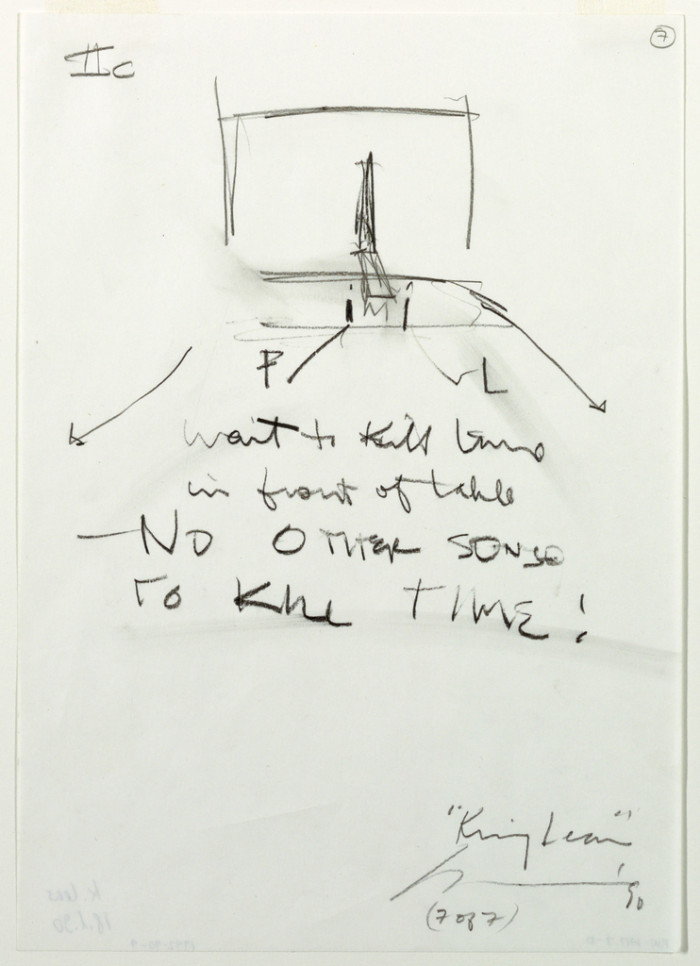

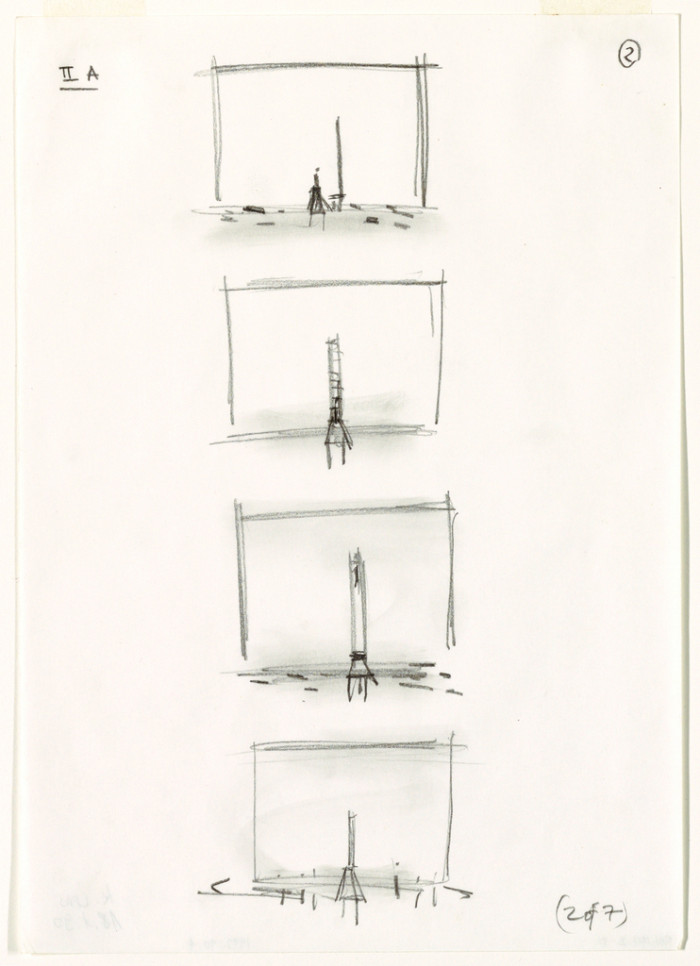

In a 1988 Parkett expose, Hans-Thies Lehmann determined that the director’s scenography might allude to surrealist paintings, with their depictions of slow moving dream-states. “The settings are unnatural and at the same time imbued with a trivial beauty, their components display a highly stylized awkwardness suggestive of a child’s drawing.”[6] Though off-kilter compositions of symbols—with little connection to traditional narrative—appear in many of Wilson’s works, this particular drawing for King Lear is far sparer. It offers a preliminary interior setting for Scene II of the play. The proscenium stage is indicated by a thick frame and slight perspective. The backdrop suggests an almost geometric void of light—Wilson’s signature touch, expressed here in contrasting eraser marks. A bed runs sharp across from the theatre’s apron to crossover (foreground to background) while a high-backed chair is positioned to the side. The two props show Wilson’s architectural ability to juxtapose vertical and horizontal planes. Both forms are also articulated in thin eraser marks, as if carving their contours in the space. Further drawings indicate how the exaggerated chair moves and functions in other scenes. Far from being technical, these detailed supplementary sketches suggest materials, form, and even interactions between objects and performers.

Drawing, King Lear, Scene XIII: Preliminary Study, 1990; Robert Wilson (American, b. 1941); graphite support: paper; 29.7 x 21 cm (11 11/16 x 8 1/4 in.); Museum purchase through gift of the Advisory Council and bequest of Mary Hearn Greims and from Sarah Cooper-Hewitt Fund; 1992-90-17

Sketch, Design for King Lear, Scene II: Study with Tall Chair, Low Bed, and Notes, 1990; Robert Wilson (American, b. 1941); graphite on white paper; Sheet: 29.6 x 20.9 cm (11 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.); Museum purchase through gift of the Advisory Council and bequest of Mary Hearn Greims and from Sarah Cooper-Hewitt Fund; 1992-90-9

Drawing, King Lear, Scene II: Study in four small sketches with tall chair, 1990; Robert Wilson (American, b. 1941); graphite on white paper; Sheet: 29.6 x 10.9 cm (11 5/8 x 4 5/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of the Advisory Council and bequest of Mary Hearn Greims and from Sarah Cooper-Hewitt Fund; 1992-90-4

In her 1985 catalogue New Works on Paper 3, the Museum of Modern Art’s then Senior Drawings Curator Bernice Rose describes Wilson’s drawing process as a form of rehearsal. His black and white drawings test the possibilities of light and shadow before they’re translated into the actual space.[7] Over the past few years, the director has evolved his practice, working more spontaneously and drawing on site—as means to counteract any unforeseen conditions—rather than making preliminary plans.[8]

[1] Adrian Madlener, “‘The Stage Is a Canvas I Paint with Light’ Grandmaster Robert Wilson Still Leads the Field in Theatre Design,” Frame 98 (May-June 2014): 177.

[2]Madlener, 176.

[3] Bernice Rose, “Introduction,” in New Works on Paper 3 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985), 14.

[4] Holmberg, Arthur. “‘Lear’ Girds for a Remarkable Episode.” New York Times, May 20, 1990.

[5] “Robert Wilson Inszeniert von William Shakespeare,” Schauspiel Frankfurt, May 1990.

[6] Hans-Thies Lehmann, “Robert Wilson, Scenography,” Parkett 16 (1988): 45.

[7] Rose, 15.

[8] Madlener, 177.

Adrian Madlener is an MA Fellow in the Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. He is enrolled in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program at Parsons / Cooper Hewitt.