Two years ago, we launched a series of monthly blogs titled “Meet the Hewitts” in order to provide a social history of the Cooper Union Museum and its founders—sisters Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt—from 1859 to Sarah Hewitt’s death in 1930. We are supplementing that history with “Cooper Hewitt Short Stories,” brief observations about the Hewitt sisters. September’s short stories highlighted the prominent figures in Sarah and Eleanor’s world and how the museum developed after 1930. This short story, written by Sue Shutte, will delve into Sarah Hewitt’s passion for horses and riding.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Remarkable Features

Horses and carriages were utilized for transportation purposes throughout the nineteenth century, but during the Gilded Age riding and coaching became leisure activities for the upper classes. Only those with expendable income could afford to own and care for horses whose sole purpose was to be used for fun outings, driving around bucolic bridle paths and carriages roads. Equestrian pursuits were considered a suitable sporting activity for the daughter of a wealthy and influential family.

Sarah, known to have been very athletic, was introduced to the sport of riding at a young age and it became her lifelong passion—other than her desire to collect decorative objects. By her teenage years, she was taking advantage of the numerous riding trails and bridle paths in Central Park and then undeveloped areas north of 110th Street in New York City. Sarah’s scrapbooks from this time even have tintypes of some of her beloved horses pasted into them.

Sarah Hewitt, age 22 in 1881, riding sidesaddle in New York City. The building in the background was the Harry Bertholf Hotel, just south of what was then Harlem Lane, now present-day 145th Street, in New York City. It had horse racing stables for trotters and riding horses, and its location along Harlem Lane was noted for being a “great road for fast driving.” Image courtesy of the Cooper Union Archives.

(left) Tintype in Sarah Hewitt’s scrapbook of one of her horses. The image is labeled “Harold, the Last of the Saxons.” Image courtesy of the Cooper Union Archives. (right) An image of another one of Sarah’s horses found in her scrapbook. Image courtesy of the Cooper Union Archives.

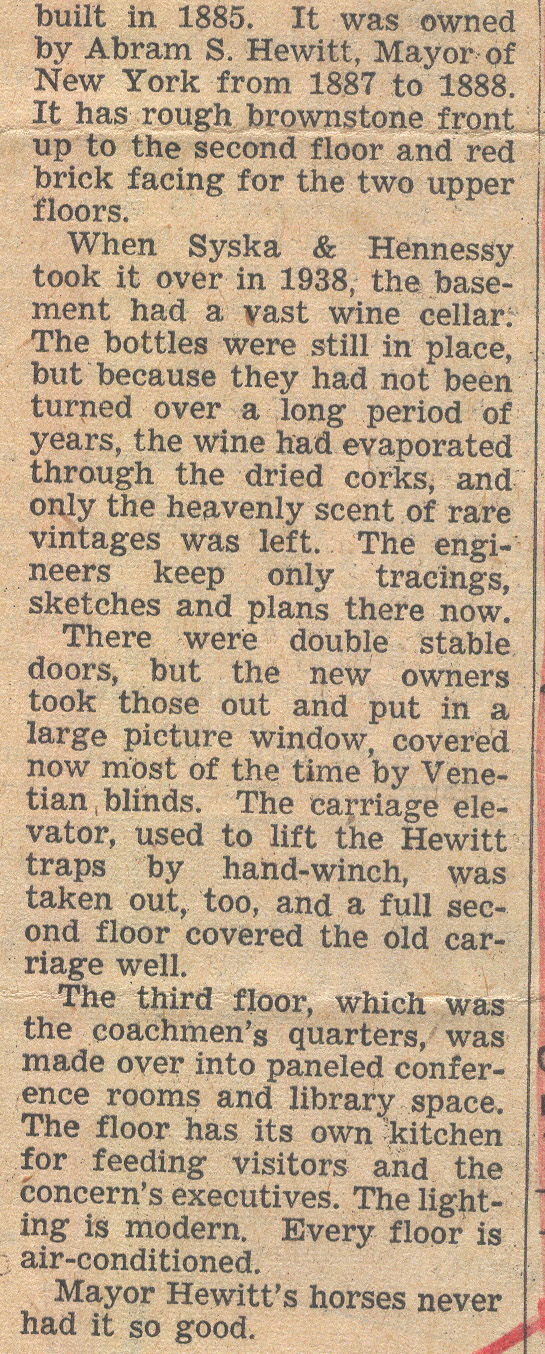

The family eventually built a stable in 1885 on East 39th Street that was three stories tall, large enough to hold a good deal of carriages and tack. An article from the New York Times described the building as having a carriage elevator that operated using a hand winch, allowing carriages to be lifted and stored on the second floor.

Image from a New York Times article dated March 25, 1957, describing the New York City carriage barn owned by the Hewitts. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

A photograph of Sarah Hewitt on horseback in the courtyard of her family’s New York City stables. Image courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

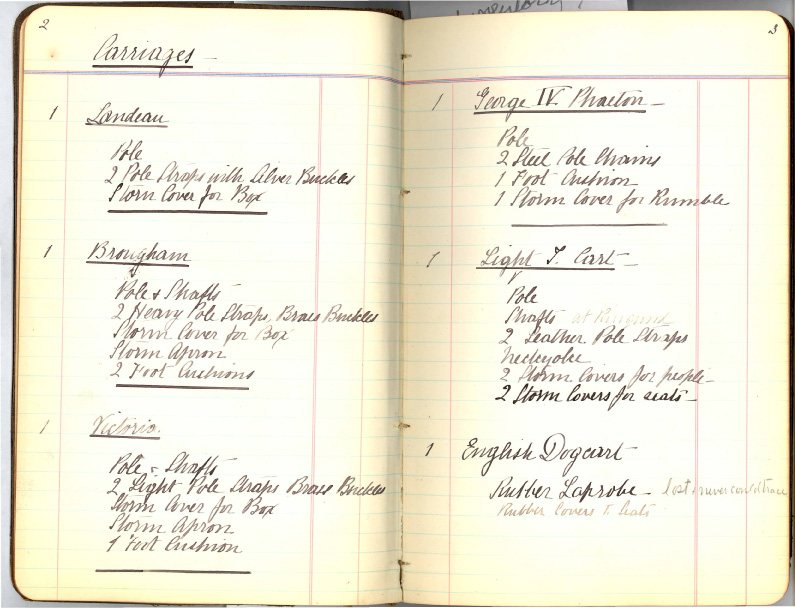

Sarah kept meticulous notes about her riding equipment, documenting the various bridles and harnesses that were purchased to go with specific carriages. An inventory notebook dated 1887–88 lists carriages, riding saddles, blankets, tack, livery outfits for the coachmen, and even the number of mounting steps she owned!

Image from Sarah Hewitt’s inventory book, dated 1887–88. Courtesy of the Cooper Union Archives.

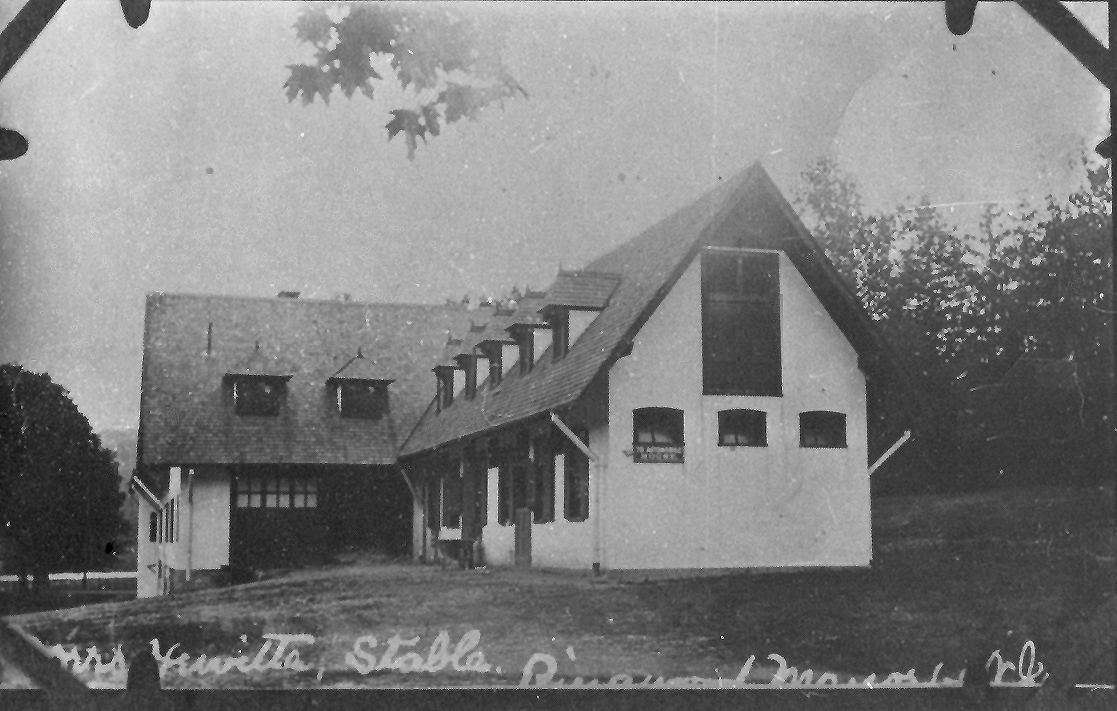

Sarah was able to expand her collection of carriage and riding equipment at the family’s summer home of Ringwood Manor. The Hewitts had purchased the country estate in the early 1800s several years before Sarah Hewitt was even born, and it had miles of scenic roads, fields, and trails perfect for horseback riding or carriage driving. According to her brother Erskine, Sarah created the carriage barn on the property by remodeling and expanding a former iron-stamping mill built around 1765. As Ringwood Manor was enlarged, so was the carriage barn, eventually reaching a length of nearly 200 feet!

The eastern end of the carriage barn at Ringwood Manor, ca. 1900. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

The carriage barn at Ringwood Manor as it appears today. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

Erskine Hewitt described the barn as having “remarkable features” that Sarah designed based on her experience with riding and caring for horses. Multiple teams of harnessed horses could drive in and out without interfering with others’ passage. The entire interior is paneled in heart-of-cypress wood. Windows were frosted to create diffuse light and only opened upwards to avoid cold drafts on the horses. The brick pavers were laid so they pitched just slightly, allowing water and waste to drain easily away from the horses.

A photograph of the interior of the carriage barn at Ringwood Manor showing the horse stalls. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

But perhaps the most innovative feature that Sarah added to the building was the gravity hay-chutes. This allowed the horses to always have fresh hay to eat, shoveled down from the hay loft above.

A photograph of the horse stalls of the carriage barn showing the hay chutes. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

Sarah continued to ride at Ringwood Manor and was noted for her ability to ride both sidesaddles and western saddles. A New York Times Society article in written in July 1887 noted that the “indefatigable horsewoman” Sarah thought “nothing of the seven mile jaunt” between Ringwood and Tuxedo Park. Where other women would have scoffed at riding such a distance through rough terrain, Sarah found it rather enjoyable! She even was documented riding the day of her sister Amy’s wedding. The New York Herald wrote:

“She [Sarah] dashed over hills, mounted on a mettlesome steed. Her appearance was striking. Picture a young girl, dressed in a loose shirt of Russian leather, wearing a corduroy skirt and Hessian boots, her wavy masses of auburn hair rolled close to the head and secured from escaping by a Tam o’ Shanter, coquettishly worn. Think of her cheeks tinged with color brought by a sharp run, still mounted, with a firm hand on the bridle and a true seat in the saddle, and one has a fair idea of Miss Sarah Hewitt.”

Detail of a saddle blanket with Sarah Cooper Hewitt’s monogram embroidered on it. Image courtesy of the Henry Ford Museum.

An English saddle once owned by Sarah Hewitt, now in the collection of The Henry Ford Museum. Image courtesy of the Henry Ford Museum.

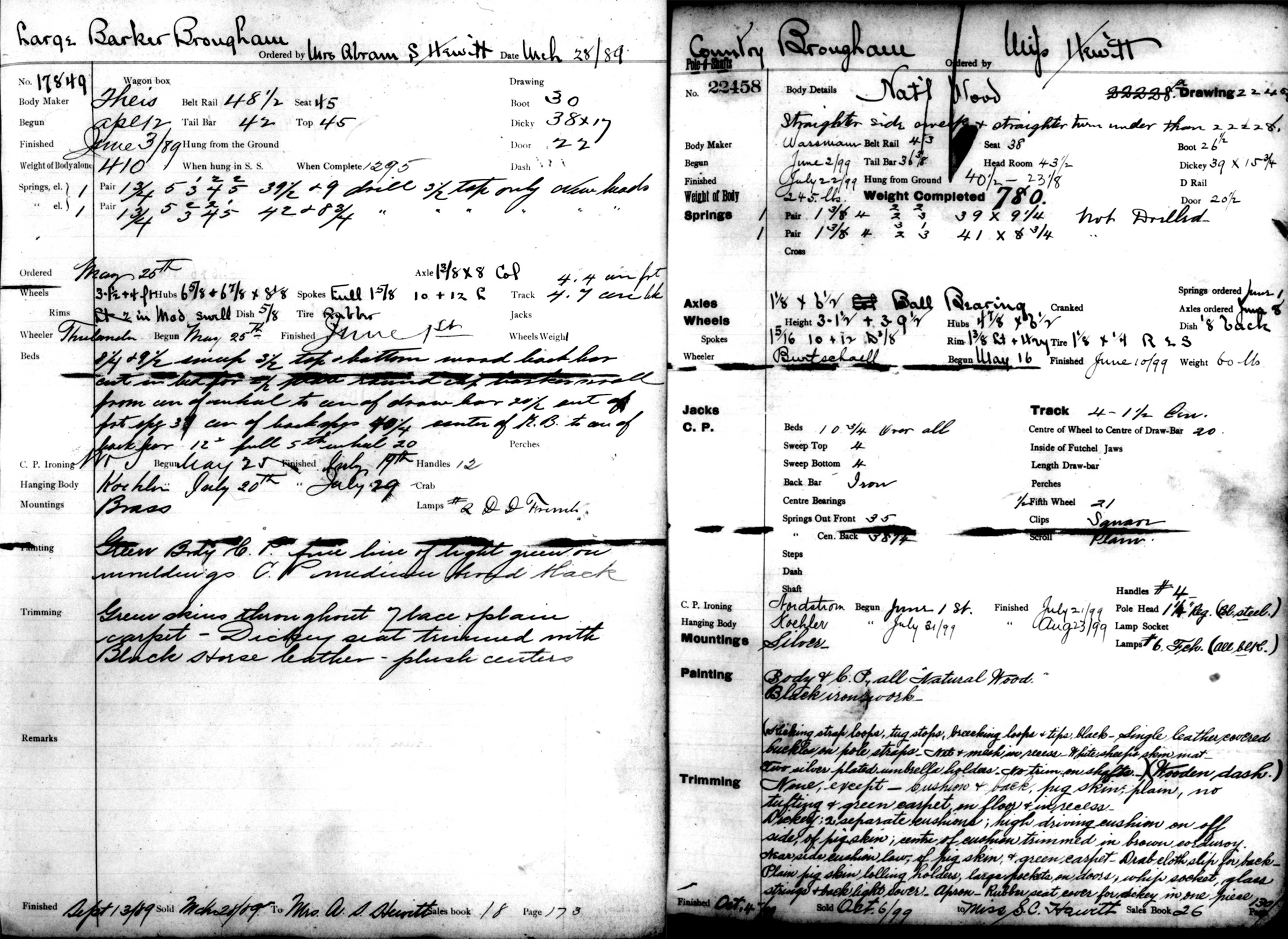

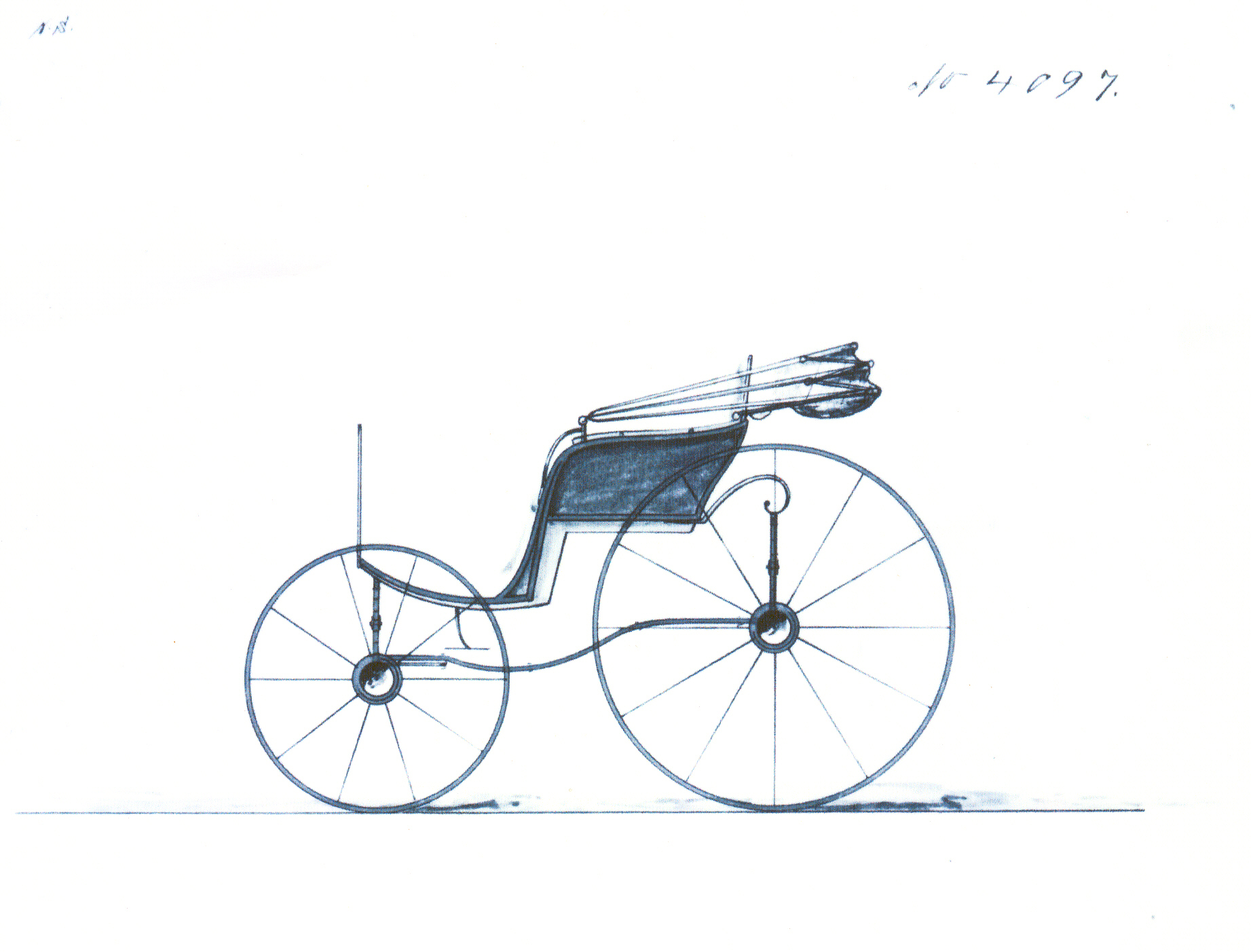

Over time, Sarah began to amass a large collection of carriages and horse tack, eventually acquiring more than forty horse-drawn vehicles in total. Many of her carriages were ordered from the Brewster Carriage Company, located at Broome Street in New York City. Brewster’s carriages were considered to be of an exceptionally high quality, and many wealthy New Yorkers placed orders for their vehicles. Sarah was no exception. Between the years 1889 and 1900, she placed no less than 11 orders for a variety of vehicles!

Brewster Carriage Company records showing orders for carriages that Sarah Hewitt purchased in 1889 and 1899. Images courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Each had customizations, from paint colors and leather upholstery to better suspension systems and larger wheels for smoother rides. Many had the Hewitt coat-of-arms painted on the sides of the carriages so passersby could easily identify the owner of the vehicle. Sarah was no slouch when it came to the sport of driving. She knew exactly what each vehicle needed in order to ensure the carriage not only looked beautiful, but also functioned at its best.

Sketch of a Brewster bell phaeton carriage that Sarah custom ordered with an upgraded suspension system allowing for a smooth ride over bumpy, unpaved carriage roads around Ringwood Manor. The drawing was a draft of the carriage that Sarah approved before any work began on building it. Courtesy of the New York City Public Library.

![The completed Brewster bell phaeton owned by Sarah Hewitt, [year?].](https://www.cooperhewitt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/18.10b.jpg)

The completed Brewster bell phaeton owned by Sarah Hewitt. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

“The Repairs of Country Roads” written by Sarah Cooper Hewitt. She notes in the introductory paragraph, “I speak from some practical experience acquired in road making in a very wild and hilly region of northern New Jersey…” Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

A sketch from the Ringwood Manor guest books showing a carriage being driven along the countryside, possibly along the bridle roads at the Ringwood estate. The sketch was drawn by Sarah’s brother-in-law, Dr. James O. Green. It’s curious to note the driver of the carriage is a woman, and perhaps a depiction of Sarah herself. Courtesy of Ringwood Manor.

As she approached her later years, Sarah began to make plans for her beloved equestrian equipment. Knowing that she had no children of her own, and also recognizing the historic value of her carriages, she searched for a location that would accept all the items as a group to be displayed and enjoyed by the public. When the Museum of the City of New York declined her potential donation due to lack of space, she approached the Henry Ford Museum, a relatively new endeavor at the time located in Deerfield, Michigan. They gladly accepted. Ever the philanthropist, Sarah had four railroad boxcars containing more than forty horse-drawn carriages, wagons, sleighs, and carts, along with saddles, blankets, clothing, and tack shipped to Michigan in August of 1930.

Brewster landau, once part of Sarah Hewitt’s collection, now owned by the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan. The carriage was used to bring Abram Hewitt and Theodore Roosevelt to Columbia University in 1899 when Roosevelt received an honorary degree, and again in 1924 when the Abram Hewitt’s granddaughter, Eleanor Margaret Green, wed Prince Viggo of Denmark. The Hewitt family coat-of-arms is painted on both sides of the body of the carriage. Courtesy of the Henry Ford Museum.

Over time, the Henry Ford Museum sold part of the collection, including several of Sarah’s carriages. Ringwood Manor has been most fortunate to be able to reacquire two of these pieces. In the spring of 2016, restoration work began on the interior of the carriage barn on the property. It is hoped that by the spring of 2017, this space will be opened to the public for the first time, showcasing these extraordinary pieces along with other equestrian-related items that once belonged to Sarah.

Visitors can get a sneak peek at the interior of the carriage barn during Ringwood Manor’s Grounds & Gardens Tours, taking place each Sunday at 2pm through the end of October. The grounds of the National Historic Landmark are open to the public every day of the year, from 8am to 8pm. Information regarding directions, tours and events at Ringwood Manor, along with history of the site, can be found by visiting ringwoodmanor.org.

Sources

Hewitt, Erskine. The Forges and Manor of Ringwood: Guide to Some of the Outdoor Items of Interest and Relics. Self-published, New York, NY. 1935.

Hewitt, Sarah. “Repair of Country Roads,” Harper’s Weekly, February 1893.

–. “About New York: Busy Season Starts for Easter Egg Jewelers- Engineering Ideas Born in A Stable,” New York Times, March 25, 1957.

–. “Society Topics of the Week,” New York Times, July 3, 1887.

–. “Ways of the World: Miss Sarah Hewitt in a Picturesque Riding Costume,” New York Herald, November 16, 1886.