“The tops of mountains are among the unfinished parts of the globe, whither it is a slight insult to the gods to climb and pry into their secrets, and try their effect on our humanity. Only daring and insolent men, perchance, go there.” – Henry David Thoreau, “The Maine Woods”

Praised by his mentor Thomas Cole (1801-1848) for possessing “the finest eye for drawing in the world,” Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) went on to secure a reputation as one of the greatest American landscape painters. Although he is one of the best known artists associated with the style of the so-called Hudson River School, Church’s wanderlust led him to travel to the far corners of the globe to source scenery for his iconic, large-scale landscape paintings, including a trip to the Andes in the late 1840s (which resulted in a 10-foot long canvas, The Heart of the Andes), the icy waters of Labrador in 1859, and the wilderness of Maine in the latter decades of the 19th century.[i]

The grand compositions that resulted from these voyages, often measuring over 6 feet in length and packed with naturalistic scenery and minute detail, were born from the hundreds of oil sketches that Church produced while traveling. These sketches, often created en plein air in pencil and crayon and notable for their loose, impressionistic quality, are a marked contrast to the highly polished final paintings for which Church is revered.

Cooper Hewitt owns the largest collection of Church’s preparatory sketches in the world. In 1917, after a year of correspondence and several visits with landscape painter and art critic Eliot Clark, who often acted as an agent for the Hewitt sisters (the founders of the museum), Louis P. Church donated 2,035 of his father’s works to the museum, including 514 oil sketches and 1,521 drawings. Clark, who had boldly made contact with Church after hearing rumors from friends in the region of a trove of sketches still held at Olana, the Church family estate, believed that the value of the collection lay not in the aesthetic value of the studies, but in the insights they provided into the Church’s method of study and the creative process by which he arrived at a finished work.[ii]

Church made his first visit to Maine’s famed Mount Katahdin in the early 1850s, tempted by the description of a “stern and savage wilderness” in an essay published by Henry David Thoreau in 1848, which would later become the excursion novel “The Maine Woods.”[iii] Set in north-central Maine, Katahdin, one of the highest peaks in New England, marks the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. With few competing foothills, the mountain, born of glacial and volcanic activity, rises dramatically in isolation from the surrounding landscape, a tempting view for any landscape painter. Church returned to sketch the mountain several times throughout the 1870s and 1880s, even bringing along his colleagues Lockwood de Forest III, Sanford Gifford, Horace W. Robbins and A.L. Holley in 1876.[iv]

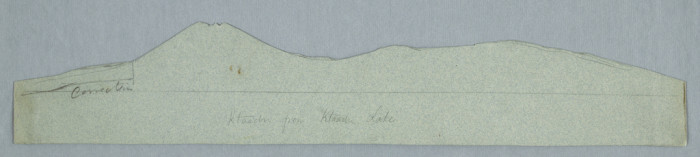

Drawing, Cut-out of Mount Katahdin Ridge, Maine, ca. 1856–60; Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900); USA; graphite on gray paper; 8 x 44 cm (3 1/8 x 17 5/16 in.); Gift of Louis P. Church; 1917-4-1527

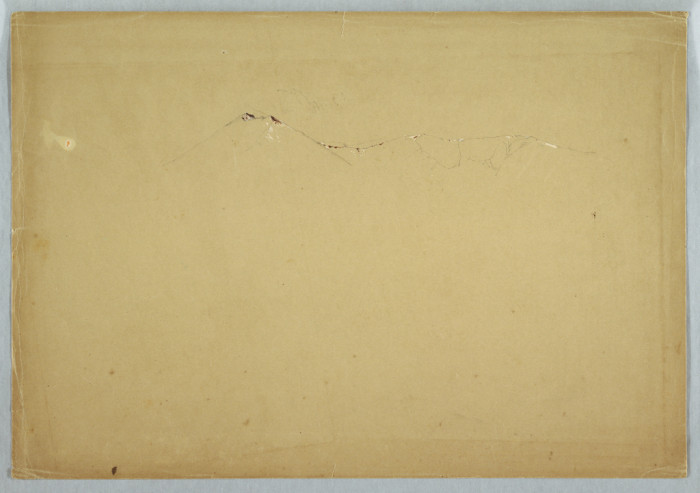

Corresponding exactly in size and shape to the mountain in each of the two sketches shown here, this large paper cutout of Katahdin ridge, measuring over 17 inches in length, was clearly used as a sort of stencil to aid Church in planning out his compositions. Cooper Hewitt’s Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design department holds over 50 sketches of Katahdin alone from the multiple excursions Church took to the region. They include scenes of the mountain from differing vantage points and at different times of day, in addition to studies of the vegetation, the texture of the ridges, and the area where the foot of the mountain meets Katahdin lake. These more detailed sketches, which record Church’s impressions of the scenery, often include notations about color and light effects. Upon returning to his studio, Church would study these sketches and, with the help of his trusty stencil, would weave these preparatory designs into a more finished composition.

These three pieces from the collection provide the deeper insight into Church’s design process that Eliot Clark and the Hewitt sisters had hoped for when building the museum’s collection of drawings. In conjunction with over one hundred preparatory sketches by Thomas Moran and several hundred more by Winslow Homer, these holdings are an invaluable resource for scholars and artists alike into the methods used by some of the most famous of American painters at the end of the 19th century.

Drawing, Outline of Mount Katahdin, Maine, ca. 1856–60; Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900); USA; graphite, brush and oxidized white gouache on cream-colored paper; 31 x 44.7 cm (12 3/16 x 17 5/8 in.); Gift of Louis P. Church; 1917-4-1526

[i] Kevin J. Avery. “Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chur/hd_chur.htm (August 2009)

[ii] Gail S Davidson. “Eliot Clark and the American Drawings Collection at Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.” Archives of American Art Journal 34, no. 4 (1994): 2. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557541.

[iii] John Wilmerding. Maine Sublime: Frederic Edwin Church’s Landscapes of Mount Desert and Mount Katahdin. (Ithaca, N.Y.: The Cornell University Press, 2012), 23.

[iv] A.L. Holley, “Camps and Tramps about Ktaadn,” Scribner’s Monthly, vol. 16 (May 1878), 33-47.

Ria Murray is a graduate student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered jointly by the Parsons School of Design and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a Fellow in the museum’s Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department.