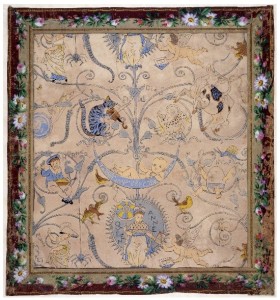

As one of the best-known British decorative artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Walter Crane’s design touched upon the fields of books, textiles, wallpaper, stained glass, and ceramics. Children’s education played a considerably important part in the subject matter of Crane’s book illustration and wallpaper designs. In 1875, Crane (1845-1915) was commissioned by Jeffrey & Co. to design a series of nursery wallpaper designs based upon his children’s book illustrations. After his first wallpaper, The Queen of Hearts, comprising Bo Peep and Little Boy Blue, issued in 1875, his second nursery wallpaper (above) was created in the following year. It features naturalistic and pictorial themes, which are typical characteristics of Crane’s style in the 1870s.

Nursery Wallpaper, Color Machine Print on Paper, 1876, British, Walter Crane. Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Wallcoverings department of the Cooper Hewitt museum holds a fragment of this design, while a complete piece found at the Victoria and Albert Museum portrays more details, which contain more classic plots of popular English nursery rhymes. The characters of nursery rhymes from Little Miss Muffet, Queen Anne, Hey Diddle Diddle, Little Jack Horner, Hush-A-Bye, Humpty Dumpty, and Frog Went A Courtin were selected and designed to correspond with the symmetrical form of the vine leaf scroll. Looking at the Cooper Hewitt’s wallpaper, in the upper left, Little Miss Muffet is frightened away by a hanging spider beside her; in the center, Queen Anne holds a sun-shaped parasol and receives letters of the alphabet from cupid; in the upper right side, a frog is handing over a plate inscribed “Miss Mouse” to a mouse. In the lower half, the dish ties the white dinner napkin to the spoon, both of which are running away, and the cat stands on the left branch of leaves playing the fiddle, while the cow jumps over a crescent-shaped moon.

As Christine Woods argues, Crane’s nursery papers were produced by machine printing owing to the fact that hand-printed wallpaper for general use was exceedingly pricey. Even so, machine-made production of nursery paper was still high-priced at 2 shillings 6 pence per roll, thus working class consumers, who pursued their aesthetic taste in the homes, still could not afford the price of nursery wallpaper.

This wallpaper was previously on display in 2007 as a part of the exhibition Wall Stories: Children’s Wallpaper and Books.

Weixin Jin is a graduate student in the Design History and Curatorial Studies program at Parsons / Cooper Hewitt and works in the Smithsonian Design Library. Jin is a researcher in the fields of Decorative Design and Museum Studies, and a lead author of Design Museum that was published in 2014.

1) Christine Woods, “Wallpapers,” in Walter Crane as Artist Designer and Socialist, ed. Greg Smith and Sarah Hyde. (London: Lund Humphries in association with the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester, 1989), 130.

2) Aymer Vallance and Walter Crane, “A Designer of Paper Hangings. An Interview with Mr. Walter Crane,” The Decorator and Furnisher 25 (1895): 223.

3) Christine Woods, “ ‘A Marriage of Convenience’: Walter Crane and the Wallpaper Industry,” in Walter Crane as Artist Designer and Socialist, ed. Greg Smith and Sarah Hyde. (London: Lund Humphries in association with the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester, 1989), 60-62.

4) Ibid., 63.