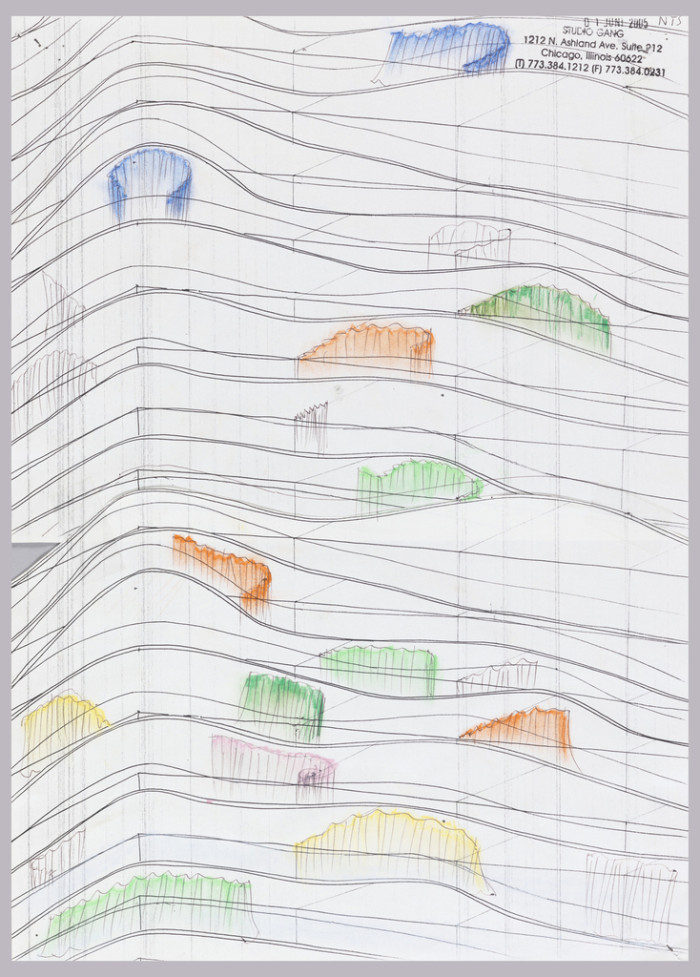

Though it is frequently lauded as the tallest skyscraper designed by a woman in the world, Chicago’s Aqua Tower is worthy of praise beyond the gender of its architect, Jeanne Gang, a MacArthur fellow and winner of the 2013 National Design Award in Architecture. The key aspects of Gang’s LEED certified design, which explores the dialogue between nature, architecture and social space and goes far beyond the obviously pleasing aesthetics of a rippling concrete and glass façade, were born in preparatory sketches like this early pencil-on-graph-paper study of the site’s topography. Cooper Hewitt owns a number of early drawings by Gang and her team for the building.

Studio Gang reinterpreted the concept of topographic levels when designing Aqua; the tower was imagined as a vertical landscape of hills, valleys and pools[i] realized in cost-effective materials: concrete and glass. Aqua’s underlying form, a straight-sided rectangle, is a relatively simple counterpoint to its complex exterior. Clad in a series of thin, concrete balconies, each of which was individually cast in a slightly varied curve using a reusable, flexible metal edge,[ii] the enlivened surface of the building toys with light, shadow and reflection, all the while belying its multiple functions: to facilitate social interaction between neighbors, to allow sunlight to reach different parts of the building while shading others, and to provide each balcony with a different view of the surrounding landmarks, including the Bean, Millennium Park and Lake Michigan, as noted in Gang’s early sketch.

Drawing, Aqua Tower, Chicago, Illinois, USA: Early Concept for Mobile Privacy Screens on Terraces, September 2007; Architect: Studio Gang (United States); pen and black ink, graphite, color pencil over photocopy, two joined sheets of white paper; Gift of Studio Gang Architects; 2014-4-11

Described by Gang as “topography on the outside of a building,”[iii] the balconies serve yet another important function: to protect the tower from the force of the wind, one of the most difficult aspects of skyscraper engineering and an especial challenge in the Windy City of Chicago. The rippled surface of Aqua breaks up the wind so much that the building did not require a tuned mass damper — a device weighing hundreds of tons that engineers typically place at the top of tall buildings to stabilize them against the vibrations and sway caused by wind.[iv] The dissipation of the winds even allowed Gang to put balconies all the way up to the 82nd floor (the top of her building), while most residential towers do not have outdoor spaces above sixty or seventy floors.

Gang’s commitment to sustainable architecture and her sensitivity to the specific challenges and advantages of the site resulted in a skyscraper that is both an inspiring and understated approach to environmentally aware design and a striking addition to the Chicago skyline. This makes Aqua appealing to both to real-estate developers and architectural critics like Paul Goldberger, who notes that “not many buildings like that get made at any height, or by architects of either gender.”[v]

[i] http://studiogang.com/project/aqua-tower

[ii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDPb7Fhd1OE

[iii] https://vimeo.com/175563995

[iv] Paul Goldberger, “Wave Effect,” The New Yorker (New York, NY), Feb. 1 2010.

Ria Murray is a graduate student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered jointly by the Parsons School of Design and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a Fellow in the museum’s Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department.