The Aldape family in front of their newly constructed home in Mercedes, Texas. The core portion of the home can be seen on the left.

CS: Juanita, as the director of LUPE, you have worked to improve conditions in the colonias since bringing this organizing model to the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) in 2003. What is a colonia, and what issues do families face living in these rural, unincorporated developments? How does LUPE work with families to prioritize and address problems?

JV: Colonias are unregulated subdivisions created by predatory developers on worthless land along the US–Mexico border. Lots are sold to low-income immigrants with only a small down payment and high interest rates (up to 21 percent). They don’t receive a title until completely paid. Residents build houses in phases as they are able to afford materials. There are close to 3,000 colonias in Texas. The majority of residents are US-born Latino, and an estimated 60 percent live below the poverty line, with unemployment rates as high as 50 percent. They are characterized by substandard housing, fouled water supplies, rampant chronic diseases, with little or no infrastructure such as electricity, plumbing, paved streets, mail service, and streetlights. Families face drainage issues, lack of affordable housing, and lack of recreational areas for the children like parks, bike and walking trails, transportation issues. I am happy to say that after many years of work we have won the issue of streetlights. It is now the law that colonias in Hidalgo County will be lit after residents go through the application process.

CS: Brent, you founded bcWORKSHOP (bcW)—a nonprofit community design resource seeking to improve the livability and viability of communities—in 2005. What communities does bcW generally work with? How did you begin to work in the Rio Grande Valley?

Brent Brown (BB): We began in Dallas working with neighborhoods and community organizations mostly in South Dallas. Today, we work across many geographies in Texas, with staff offices in Dallas, Houston, and Brownsville. Our work in the Rio Grande Valley started with a response to an invitation by the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville (CDCB) to work with them on a new multifamily affordable- housing project. We were awarded that project because of our community-centered approach, and our willingness to push the alternative-development approach CDCB was proposing.

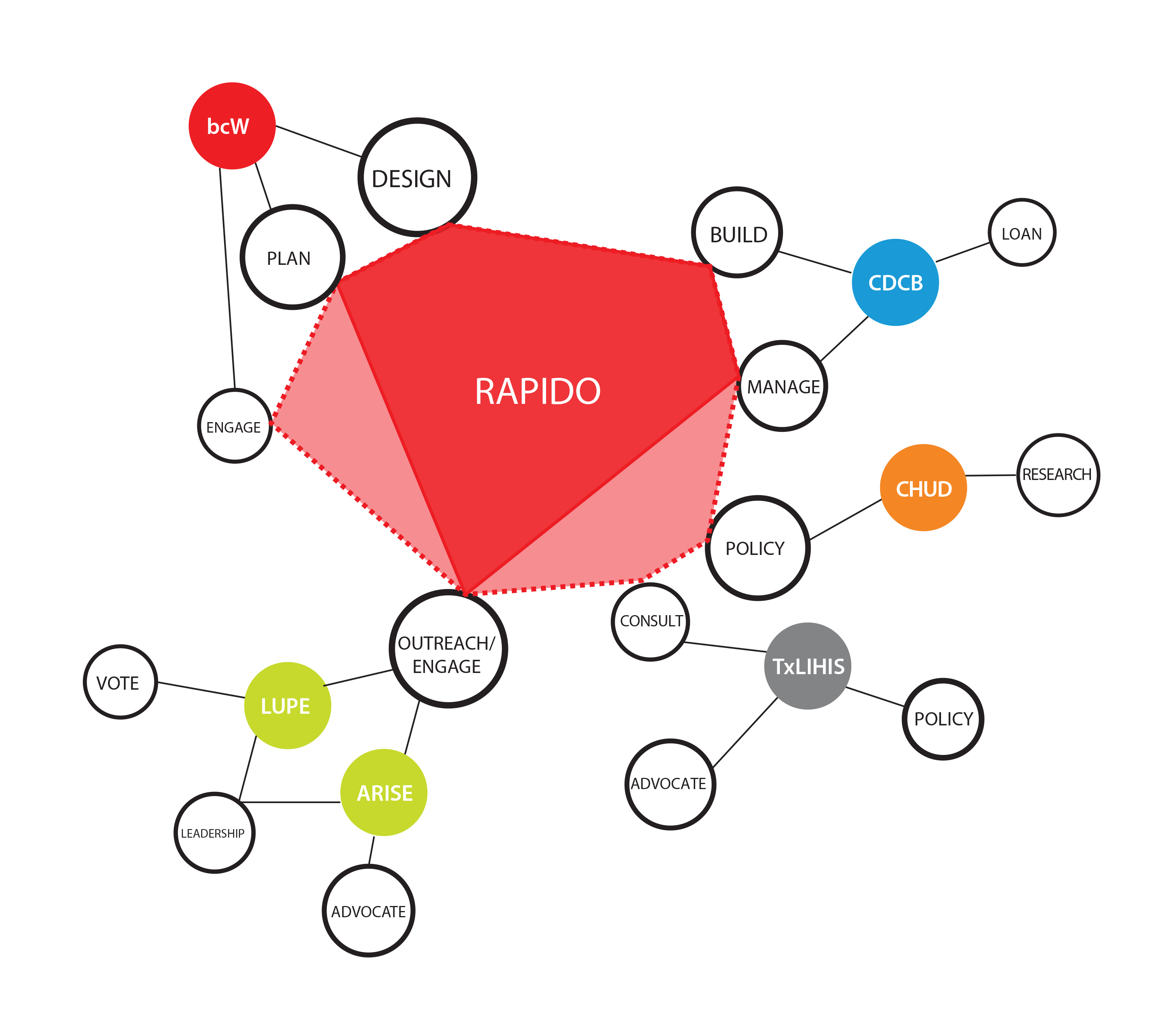

Diagram illustrates the multidisciplinary RAPIDO team’s process to deliver low-cost postdisaster housing prototypes.

The Gurley Place Senior Apartments designed by bcWORKSHOP, in Dallas, Texas, face the Jubilee Park Community Center recreation space. The housing’s “eyes on the street” design supports a safer neighborhood for all residents.

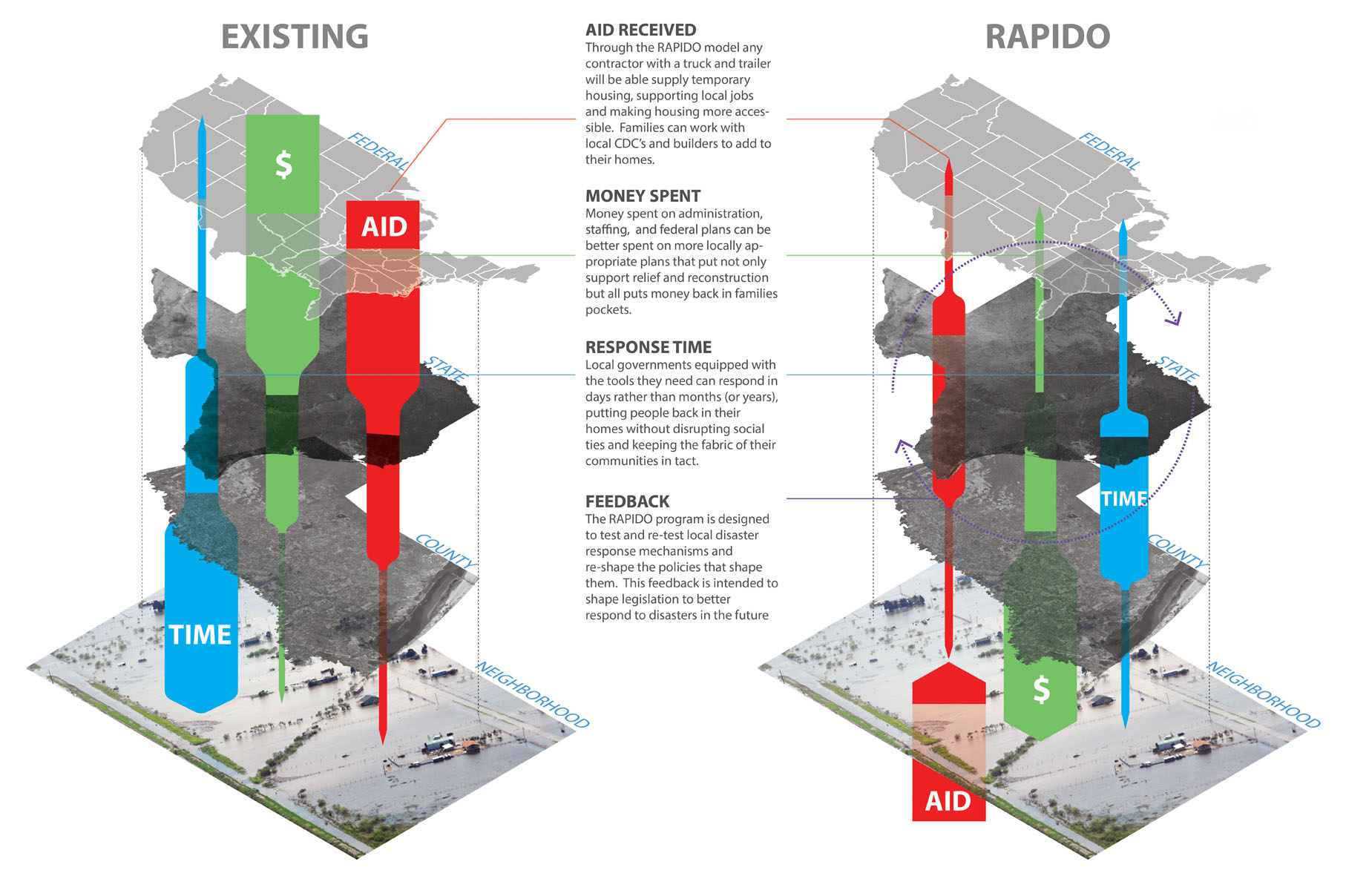

The RAPIDO model reworks the entire system, from the federal policies that shape disaster response, to the residents who are affected by a storm. By shifting the components of disaster response, the team hopes to support local economies, provide more appropriate response solutions to local communities, and reduce the time needed get people back in their homes after a disaster.

Congo Street, which had experienced flooding, was redesigned in 2012 by bcWORKSHOP. The first green street in Dallas, the design utilizes permeable pavers and bioswales.

CS: Brent, what critical steps does your design team use in a community-engaged design practice? Why are these steps important?

BB: We engage. We listen. We work to confirm that what we hear is what was meant. And, then we ensure the design advances the community’s interest, even if we have to build it. In order to practice in a public-interest way, trust must be present. If it’s not—and often times there is plenty of skepticism—there must be the hope or opportunity for it to exist; by engaging, listening, confirming, and acting, trust can be built.

Brent Brown with residents at an early design meeting on Congo Street with the Garrett family in Dallas, Texas.

LUPE (La Unión Del Pueblo Entero) and ARISE (A Resource in Serving Equality) hold a community outreach meeting at LUPE headquarters in San Juan, Texas, to discuss the details of the RAPIDO process and gain feedback from community members.

LUPE and ARISE hold an informal gathering in San Juan, Texas, to discuss the severe gap in planning resources delivered to south Texas’s modest neighborhoods.

CS: RAPIDO is unique in that it provides immediate housing after a natural disaster. Why is this important? How were the twenty RAPIDO families selected to receive replacement houses—by need, location, or other reasons? How long was it before they could move from the CORE housing into the expanded custom home? Could they remain in the house during the expansion?

BB: While family and community fabrics are resilient, they can degrade and lose the strength that is most needed after a disaster. Families, friends, support networks being geographically displaced over time degrades and disrupts the fabrics. It is important to keep that geographical displacement as short as possible. With RAPIDO, we took it a step further, and tried to make the system of rebuilding actually support the community fabric by aligning with local economies, and an open-source system of construction, allowing families to add and modify as needed. The families selected were all within the highest- damage zones associated with the storm. From there, we allocated a certain number of units per county based on need and population. This was a pilot effort, and we did not ask the families to live in the cores that we built while we built the house around it. In an ideal scenario, poststorm, families would be able to move in the expansion after four to six months, but this depends on a number of factors, including the ability to secure environmental clearances and a host of other process-related requirements. We included in our policy and technical recommendations many very specific actions needed to streamline this process, saving time and improving reliability for the family. The families can remain in the house during its expansion.

CS: Juanita, LUPE has been collaborating with new partners. How has that worked?

JV: We have been able to collaborate in a way that we had not been able to. In all my years at the union we had never worked with architects or planners and the allies that we now have. And what we’ve found is that by everybody taking a piece of the problem that we’ve made a lot more progress, and it’s been a better- founded progress in a way that is longer lasting. When we were organizing the colonias and it was flooding, what we saw was the water and flooding and the homes being damaged. We really couldn’t get to the root of the problem like the architects and the planners were able to. It brought a longer-lasting solution to the problem. Working with the architects and planners from bcWORKSHOP has brought more credibility to the work plans that colonia residents develop. Elected officials take colonia residents more seriously when presenting their work plan because they have been developed with the assistance of experts.

The Salas family’s home in Edinburg, Texas, before construction began. The majority of families seeking disaster- reconstruction funding were denied because they had not been able to keep up maintenance on their homes. Given the state of extreme poverty in the region, this left many without any alternatives.

This interview is excerpted from the book By the People: Designing a Better America.