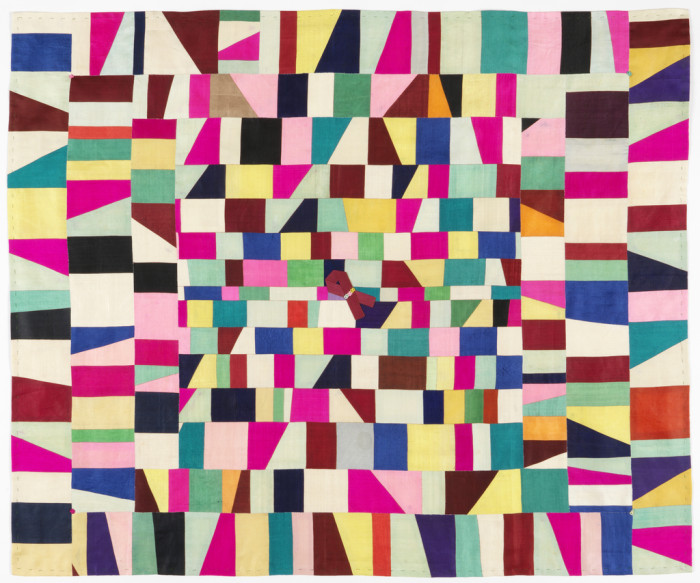

Wrapping Cloth (bojagi) (Korea), ca. 1900; silk; 82.2 x 90.2 cm (32 3/8 x 35 1/2 in.); Museum purchase from Roy and Niuta Titus Foundation Fund; 1994-22-1

Bojagi cloths were essential elements of Korean households since the very beginning of the Joseon Dynasty in the late fourteenth century up until the 1950s. Equally used and valued by Korean peasants, working classes, and royalty, these multipurpose textiles combined functionality, aesthetic, and craftsmanship. They served a variety of functions including wrapping gifts, covering cooked food from insects and rodents, and textile carrier. Bojagi were usually made of a large square-shaped fabric in cotton, ramie, hemp, and silk. These textiles featured a variety of styles and were split in two main groups: kung-bo for the royal court and min-bo for the ordinary people.

Wrapping Cloth (bojagi) (Korea), ca. 1900; silk; 85.1 x 101.6 cm (33 1/2 x 40 in.); Museum purchase from Roy and Niuta Titus Foundation Fund; 1994-22-2

Patchwork was the most frequent technique. Called jogak-bo, or chogak-po, which means “small segments” in Korean, this type of folk textiles was made by women and it required the use of scraps. The traditional craft of Korean patchwork offers a joyful array of colors masterfully pieced together, striking designs that could easily be hung on the wall like abstract paintings. By the early sixteenth century, Chinese Neo-confucian doctrine had widespread and radically impacted Korean society, women social status in particular. In this patriarchal system, women lost their economic independence and were reduced to their role of wives. [1] Essentially leading lives isolated from men, they spent most of their time taking care of their home, and dealing with their household belongings with care and thrift. Women made clothes for their family and retained all the off-cuts. They sorted these textile leftovers by weight, material, and color. Then they cut them into geometric pieces such as squares, rectangles, triangles, and trapezoids, and skillfully patched them together into colorful, free-hand compositions.[2] Reclaiming garments’ off-cuts into new cloths was considered an auspicious practice in Korea. The makers explored their own creativity and expressed their good wishes in their artworks, bringing happiness, luck, and longevity to the future owner. [3] Since the 1990s, there is a strong bojagi revival, especially patchworks, in Korea, within the diaspora, and beyond. Contemporary Korean artists and designers such as Youngmin Lee, Chunghie-Lee, and EunSook Lee praise jogak-bo for its infinity of designs and its playful and vibrant colors.These modern interpretations redefine an ancestral technique and explore its potential as a versatile three-dimensional surface, beyond bojagi’s utilitarian primary function. [4]

[1] Dorothy Ko, JaHyun Kim Haboush, Joan R. Pigott, eds., Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern China, Korea, and Japan, Berkeley: California University Press, 2003, 143.

[2] Kumja Paik Kim, “A Celebration of Life: Patchwork and Embroidered Pojagi by Unknown Korean Women” in Creative Women of Korea: The Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries, Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2003, 167, accessed February 12, 2016, https://books.google.com/books?id=-aywPkc1CEUC&dq=The+wonder+cloth+huh&hl=fr

[3] Chung Ah-young, “Bojagi workshop offered at LACMA” in Korea Times US, March 27, 2014, accessed February 12, 2016, http://www.koreatimesus.com/bojagi-workshop-offered-at-lacma/

[4] Maria, Tulokas, “The Evolution of Bojagi” in Surface Design Journal, Summer 2014, 2014, 16-21, accessed February 12, 2016. http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=0b1ea4c4-07ca-4348-80ac-d46c721d547a%40sessionmgr115&vid=1&hid=109

About the Author

Magali An Berthon is a textile researcher and designer, focusing in particular on world textile crafts and sustainable fashion. After an MFA in textile design in Paris, she studied textile history at the Fashion Institute of Technology NY on a Fulbright fellowship in 2014. Since June 2015, she is a curatorial fellow at the Textile Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Scraps Stories

This post is part of the blog series Scraps Stories dedicated to exploring sustainable textiles and fashion, in relation to the exhibition Scraps: Fashion, Textiles, and Creative Reuse.