Last month in Cooper Hewitt Short Stories, Dr. Gail Davidson wrote about how American drawings by Winslow Homer, Frederic Church, and Thomas Moran entered the museum’s collection.

February’s Short Story twitters romance! A passionate collector pursued beautiful homes for birds. Enamored, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt bought his birdcages for their museum. Chirp! #HewittSisters

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

(Above: Bird Brooch, ca. 1850; Gold and turquoise; Gift of Rosemary Bradley Carroon in memory of Elizabeth Lewis Murray, 1991-50-1)

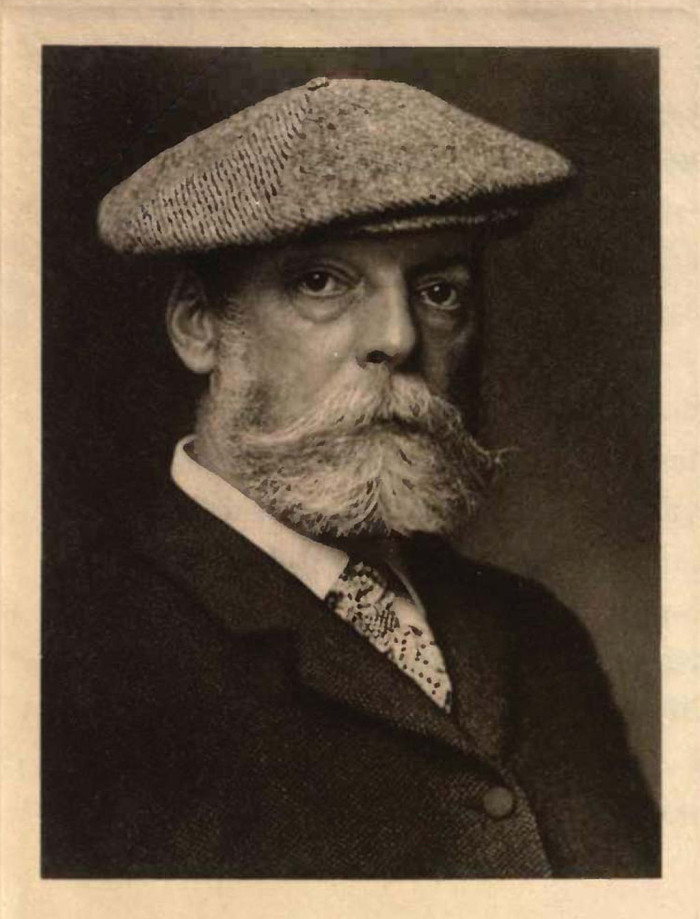

Portrait of A.W.Drake. The Century Magazine, May 1916.

A.W. Drake—Artist and Passionate Collector

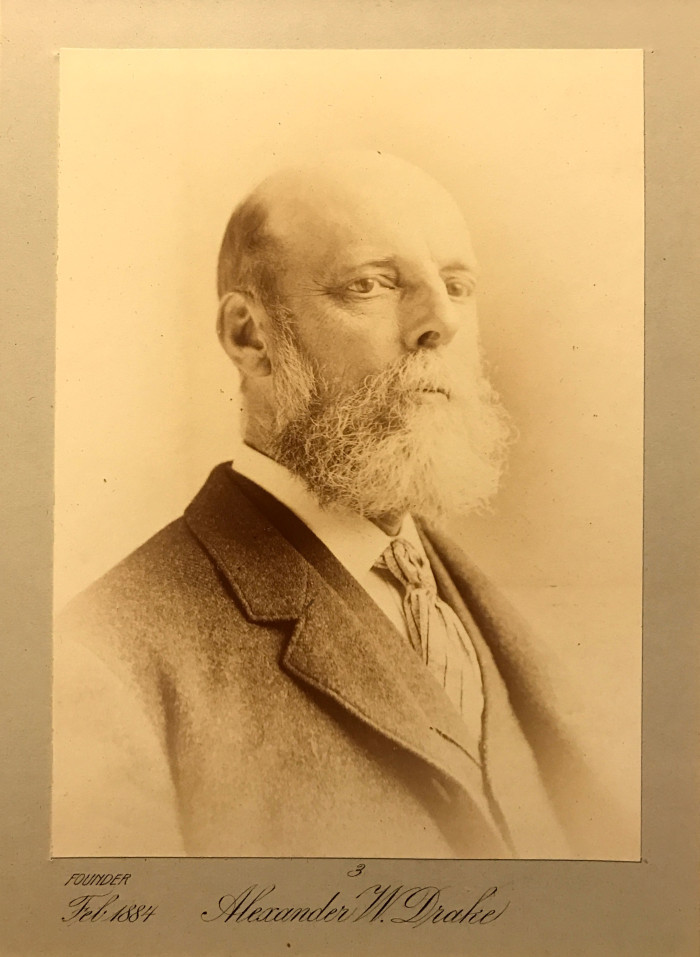

In 1913, Sarah and Eleanor purchased ninety birdcages at auction in New York City. They paid $1,300 for this collection acquired over many years by artist and collector Alexander Wilson Drake (1843–1916). Born in New Jersey, Drake was a wood engraver who studied and taught at Cooper Union. He was the esteemed art editor of The Century Magazine for forty-three years and a founding member of both the Grolier Club and the Aldine Club.

A.W. Drake, 1884. Courtesy of the Grolier Club.

Drake was noted as a zealous collector of “everything but money.” His home on East 8th Street in New York City overflowed with pewter, brass, and copper, as well as rings, bottles, silver boxes, prints, samplers, ship models, birdcages, and decorated bandboxes. There were occasions when he was forced to sell collections in order to start anew with other collections.

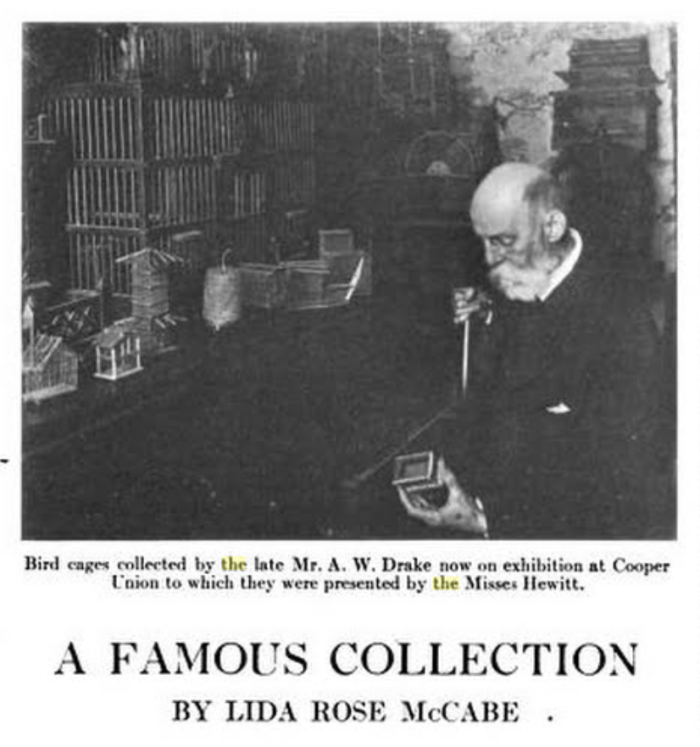

“COLLECT — if you would be happy — collect anything, everything!” begins a 1916 article in The House Beautiful by Lida Rose McCabe, who interviewed Drake about his cages before he died. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, bird cages were in vogue, prized as decorative accessories for the home. Through his love of birds, Drake began, as a boy, to collect homes designed for them.

A.W. Drake with his collection. The House Beautiful, July 1916.

“I have always been a great prowler” . . . “primitive art always appealed to me,” Drake revealed in the article. In his travels for business and pleasure, he found unique treasures skillfully made in many countries and by designers of many walks of life. Commenting on the architectural ancestry of the cages, “It is the stuffy little bird shops along city wharves, to which sailors from far off ports bring birds of every feather carrying them in their native cages, that the collector has his happy hunting ground.” The dealer buys the bird and discards the cage. “Herein steps the shrewd collector.”

Drake sought ornamental and practical birdcages for breeding and traveling, compartmented cages for several birds, and cages for singing insects and fighting crickets. The cages were made by artisans in Europe, Asia, and North and South America, and were constructed in a variety of materials, reflecting their origin, purpose, and skill of the maker.

(upper left) Multi-story cage reminiscent of a Swiss chalet, France, mid-19th century; Metal wire, painted sheet metal; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-28-a/d. (lower left) Delftware cage, decorated with scenes of Dutch domestic life, Netherlands, 1750–1800; Tin-glazed earthenware, metal wire, metal; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-60-a,b. (lower middle) Insect (grasshopper) cage, Asia, 19th century; Woven reed, gilded paper (dome), lacquered wood (base), paper, wire, and feather (insect); Gift of Eleanor and Sara Hewitt, 1916-40-1-a/d. (right) Storied (comparmented) cage for families of birds; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-30-a/d

Drake told McCabe about rummaging in unexpected, out of the way places for treasures. Each of his ninety cages had a story. Especially interesting was the discovery of the masterpiece created in wire and wood by an Italian peasant boy who skillfully reproduced the Rialto Bridge as a cage for his birds. “I was about to leave Venice when the cage caught my eye in the window of a bird dealer. I rushed into the shop and there was barely time to close the deal before the train started. . . .” A tag was tied to the cage door, and the Rialto arrived safely in America.

Rialto Bridge Birdcage, Venice, Italy, late 19th–early 20th century; Painted wood, bent metal wire, metal; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-14

“With birdcages as with all collecting,” said Drake, “the joy of the quest is not to be estimated in dollars or cents. To make collecting worth while, one must collect in large numbers.” Drake also found joy in designing table decorations, furnishing his birdcages with tiny plants and lanterns for the Aldine Club. His arrangements for a dinner honoring Mark Twain in 1900 were described as “remarkable.”

(left) Drake claimed this iridescent glass cage was made for the Queen of Italy. Birdcage, 19th century; Glass, silver-plated metal, metal, gilt wood; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-92-a/g. (middle) Church cage, “wooden gothic” style, Long Island, NY, mid-19th century; Turned, cut, and stained mahogany, cherry, pine, cut brass, wire, enamel-painted metal; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-83-a,b. (right) Miniature silver bird cage, England, ca. 1800; Silver; Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, 1916-19-104.

In 1913, ill health forced Drake to retire from The Century Magazine and to sell many of his collections. The American Art Galleries created a special catalog of his work. A friend of the Hewitt sisters, Drake made his cages available to Sarah and Eleanor, who were thrilled to purchase the collection for their museum. It was exhibited privately at their home at 9 Lexington Avenue to much acclaim, and then installed at the Cooper Union Museum where it enchanted students and visitors.

Birdcages on exhibit above the Decloux collection, Cooper Union Museum, ca. 1926.

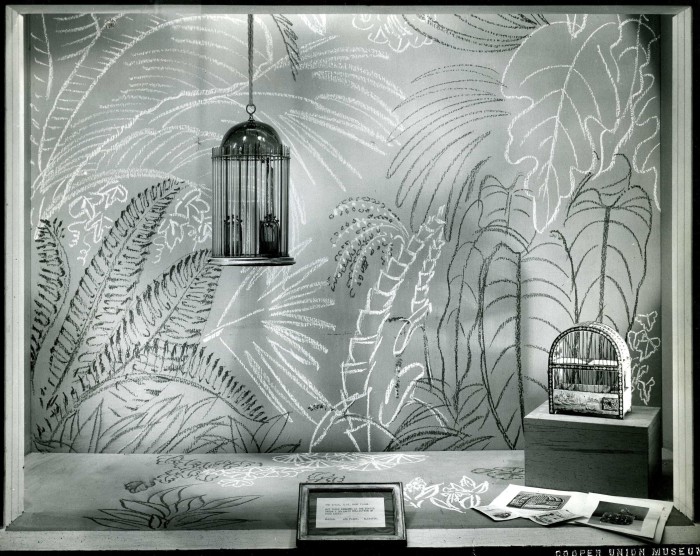

“The Birds, Alas, Have Flown Away” exhibition of birdcages from the museum in Cooper Union street windows, August 1944.

Alice Baldwin Beer, Cooper Union Curator of Textiles from 1948–70, recalled that “one of the museum’s most popular summer exhibitions in the late 1940s was of birdcages. Young ladies from fashion magazines were found sitting on the floor . . . the better to sketch some of the items.” In 1951, the Cooper Union Museum summer exhibition focused on the birdcage as a vehicle for creativity and design in cultures around the world.

Over the years, many of the cages decayed and were deaccessioned. In 1943, a large group were sold at auction by Parke-Bernet. Fourteen cages from the Drake Collection remain at Cooper Hewitt, and can be viewed on Cooper Hewitt’s website as collection higlights. In 2014, the newly renovated Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum re-opened with a special exhibition titled The Hewitt Sisters Collect. Five cages from the Drake Collection were featured—elegant, whimsical, and popular homes. ![]()

“Hewitt Sisters Collect” installation, on view at Cooper Hewitt.

Sources

“Alexander Wilson Drake,” by Clarence Clough Buel, and “An Appreciation,” by William Fayal Clarke,” The Century Magazine, May 1916.

“Alexander Wilson Drake,” obituary, American Art News, June 1916.

Beer, Alice Baldwin. “Cooper Union Museum to Cooper-Hewitt Museum: Draft of the Continuation of ‘The Making of a Modern Museum,’” 1977. Smithsonian Institution Archive, Record Unit 547.

Cooper Hewitt Design Library. Appreciation to Elizabeth Broman , a Reference Librarian at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library for her research and assistance.

Garisto, Leslie, Birdcage Book. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

McCabe, Lida Rose, “A Famous Collection,” The House Beautiful, July 1916.

Webster, Walter F. “Bird Cages” [Drake Collection], American Homes and Gardens, August 1913.