Excerpt from Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Molly Rose Kaufman, and Aubrey Murdock’s essay “The Aesthetics of Equity: A Magic Strategy for the Healthy City” from the By the People: Designing a Better America exhibition publication.

Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD HON AIA, is a research psychiatrist at New York State Psychiatric Institute and a professor of clinical psychiatry and public health at Columbia University. Molly Rose Kaufman is a community planner, journalist, and youth worker who cofounded the University of Orange, a free people’s university, worked with residents and planners to write the Heart of Orange plan, and developed ORNG Ink, a youth-led, user-driven arts collective. Aubrey Murdock is Head of School for the University of Orange, which operates on the principle that everyone has something to teach and everyone has something to learn. She focuses on the role of media and design within civic education and involvement.

Heart of Orange Map made by Michel Cantal-Dupart to illustrate “City Island.”

In public health, we like to tell the story of the man who noticed someone drowning in a river. He jumped in and pulled the man to safety. No sooner had he done that, he then saw a second man drowning. He saved that man, and then the scenario repeated itself several more times. Suddenly, the man turned and started to run. One of the people he’d saved called out, “Hey, where are you going? There are more drowning people to save!” The man shouted over his shoulder, “I’m going upstream to see who’s throwing all these people in the river!”

This is the story of how the Cities Research Group moved upstream and what we learned.

Drowning in Epidemics

Crack vials littered the sidewalk, and the door of 513 W. 166th Street sported a new bullet hole. It was 1990 and Mindy and Robert Fullilove had arrived in New York City from San Francisco to begin work at Columbia University. Their new office was located in Washington Heights, a neighborhood leading New York City in homicides related to the crack epidemic. Here, Mindy and Robert founded our organization, the Cities Research Group, where we sought to understand the myriad health epidemics ravaging low-income communities of color across the country. These epidemics included AIDS, crack cocaine addiction, violence, trauma related to violence, and multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis.

It became painfully clear that this terrible series of epidemics was concentrated in neighborhoods that had been devastated by disinvestment, their housing stock shredded, social organization in a shambles, and morale at an all-time low. The environmental destruction and the throng of epidemics were obviously connected, but how? And what was to be done?

Perhaps the most important lesson we learned was this: if there is a problem in a neighborhood, there’s a problem in the city.

We first heard this at a 1993 Paris conference on AIDS, substance abuse, and homelessness. French architect and urbanist Michel Cantal-Dupart delivered the opening address. Using the metaphor of the body, he pointed out that illness in one part of the body had to be treated with the whole body in mind. “The same is true of the city,” he said. “What is the problem we must solve? The fracture between the wealthy neighborhoods and the poor ones.”

Running Upstream

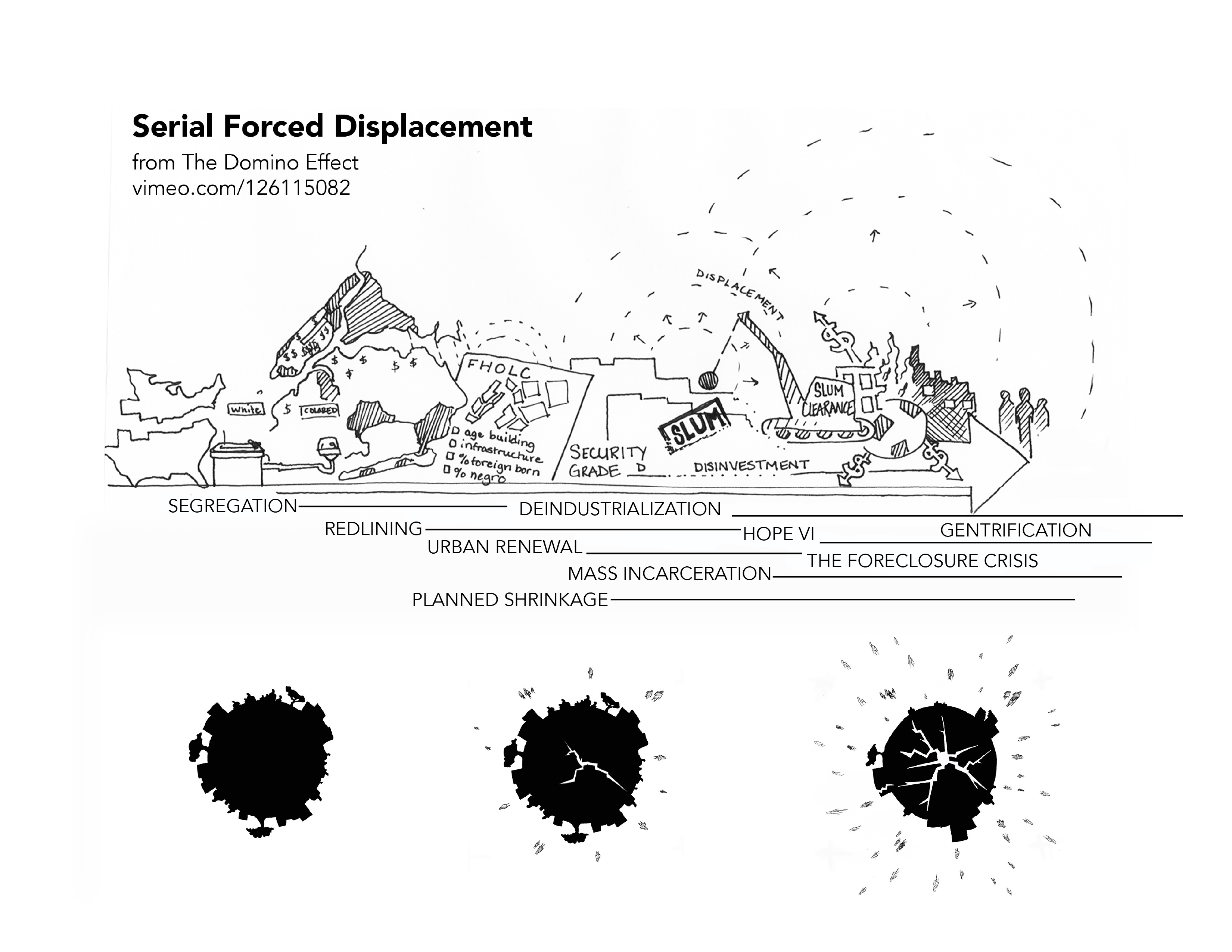

In the course of our subsequent fieldwork, we learned that urban fracture has been caused by a series of policies that have “sorted” American cities by race and class. We were able to trace the effects of segregation, redlining, urban renewal, deindustrialization, mass incarceration, HOPE VI, the foreclosure crisis, and gentrification. Because all of these policies displaced the same vulnerable populations, we named this “serial forced displacement.”

Serial forced displacement is a particularly grave threat to population health because it repeatedly attacks the very foundation of human health: the stable neighborhood that has intergenerational knowledge of how to survive in a given place. Displacement traumatizes people and destroys wealth of all kinds, including people’s economic, political, social, and cultural capital. Repeated displacement takes even more of the wealth and integrity of the weakened population. Serial forced displacement is unjust, and it creates inequity: it is a source of adverse childhood experiences, setting the stage for present misery and future ill-health.

Serial forced displacement: This drawing depicts the forces undermining the place-based stability of minority communities, names the policies that have driven displacement, and shows the ever-increasing splintering of social relationships as one policy follows another. Artist: Aubrey Murdock. From the film: The Domino Effect, 2015.

Unexpected and hazardous situations result from this constant stripping of people’s social, emotional, and financial wealth. It is in the context of urban renewal in the 1960s that civil unrest broke out in cities all over the nation. It is in the context of planned shrinkage in the 1970s that HIV exploded across the South Bronx and other NYC communities that had been subjected to the withdrawal of city services. It is in the context of deindustrialization—where jobs were reduced or lost resulting in social and economic decline—that drug-dealing became a new source of employment and the crack epidemic took hold, accompanied by massive violence, family disruption, and the spread of HIV and other infections. The official government response to that epidemic of addiction was to impose long prison sentences, unleashing an era of mass incarceration that had consequences for families and neighborhoods no one anticipated. By 2015, the New York Times reported that there were “1.5 million missing black men,” in the United States, many in prison, others who had died prematurely.

Public health leaders look at rates of disease as having three factors: the person, the environment, and the causative organism or factor. Serial forced displacement shifted the environment, making it conducive to the emergence of new health problems, like AIDS, and massive epidemics of known problems, like asthma. The disruption and impoverishment of communities weakened their ability to control these epidemics. Eventually, the medical system became caught in gridlock. Doctors could continue to see patients, but they had no treatments for the new, complicated problems they were seeing. We had no “magic bullets” to stop the spread of disease.

After assessing the existing vacuum of treatments, human ecologists Rodrick Wallace and Deborah Wallace have argued that “magic strategies”—multi-system, multi-scale health promotions—fit best with the basic biology of people and offer the most hope for the future. These are interventions that address the large-scale social inequalities and injustices, are sensitive to local culture, and include the voices of all the people. “Magic strategies” are based on a recognition of the three factors influencing rates of disease: person, environment, and causative agent. “Magic strategies” recognize that the problem has roots in all three and that changing one is not enough. We have to work in all three domains.

Designing Equity With People

By 2007, new forces were shaping New York City. Real estate values in Washington Heights spiked, and suddenly the Cities Research Group’s office was a hot commodity. We wondered where others, displaced by rising rents, were moving. One of the affordable places was Mindy’s hometown, Orange, New Jersey.

Visits to Orange revealed the historic structures that dotted the city’s 2.2 square miles. There were so many important markers of American urbanism that it became clear that anything you wanted to know about the American city you could learn in Orange. The city was a university. This idea, shared with old and new friends, led us to found the University of Orange, a free people’s university. The University of Orange was launched with the plan to offer free courses taught by volunteer faculty and to help with urban restoration by giving local residents opportunities to consult with top urbanists.

It was a timely intervention because, despite great assets, Orange was battered and discouraged, hit hard by all the noxious policies of urban renewal, deindustrialization, highway construction, mass incarceration, and disinvestment. For the Cities Research Group, the University of Orange offered an opportunity to look at “magic strategies” as a way to stabilize the city and protect the health of the residents. Our programs seek to reweave social networks, reconnect physical spaces, and promote equity throughout.

We share our approach to urbanism through our annual winter program, Jan Term, and an annual spring event called Placemaking, which engages us with the city’s public spaces to make them work for all. In both we invite organizers, designers, educators, and other practitioners to join us as urbanists in residence.

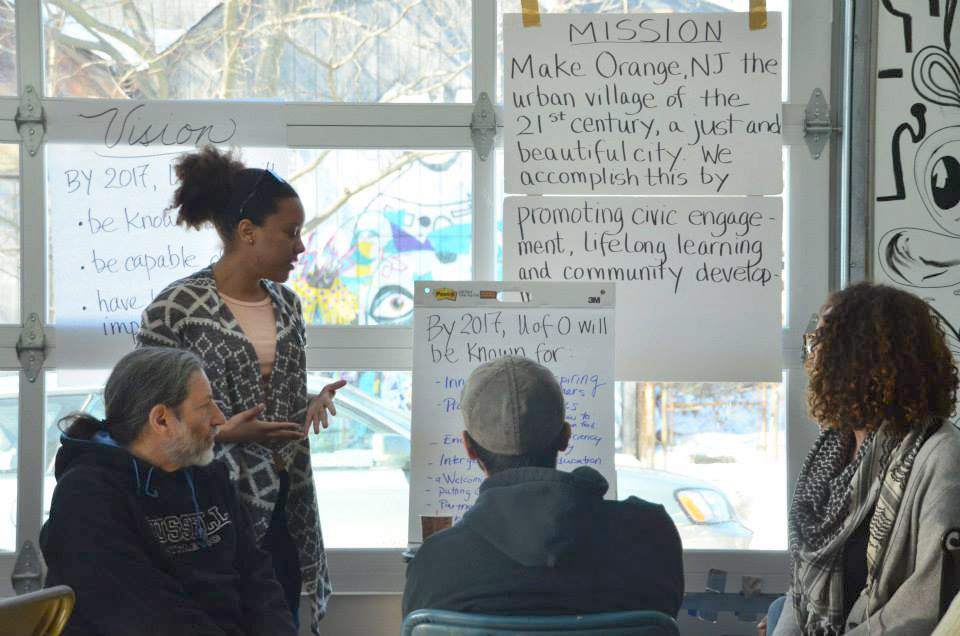

University of Orange Visioning Session. UofO Board member Rachel Bland leads a discussion of UofO’s mission at a strategic planning meeting, with (l to r) Charlie Steiner, Jeff Coleman, and Molly Kaufman.

Naming and Framing the Problem

William Morrish, a professor in the Design and Urban Ecologies program at Parsons, The New School for Design, describes “naming and framing the problem” as the first step of design. Our first consultant was Michel Cantal-Dupart, who came in 2009 to examine the issues in the center of town. He studied the area carefully, walked it with residents, examined historical maps, participated in our first annual Placemaking day of visioning, and presented us with an unexpected observation. The 1960s division of the city by the construction of a freeway—the highway later known as Route 280—was understood by all of us. But Cantal pointed out that a shift in the train line had also contributed to the fracture of the center of the city, creating a deteriorating island of buildings. “Look,” he said to us. “It is as if there are two rivers—the train and highway. In Paris we have an island like this. We call it Isle de la Cité, and it is a very popular spot. You should rethink your City Island, beautifying the ‘river banks’ and reconnecting the north and south.”

He used his blue colored pencil to show us how the train and the highway were rivers. Suddenly, City Island leapt off the page, giving us a new perspective on the city.

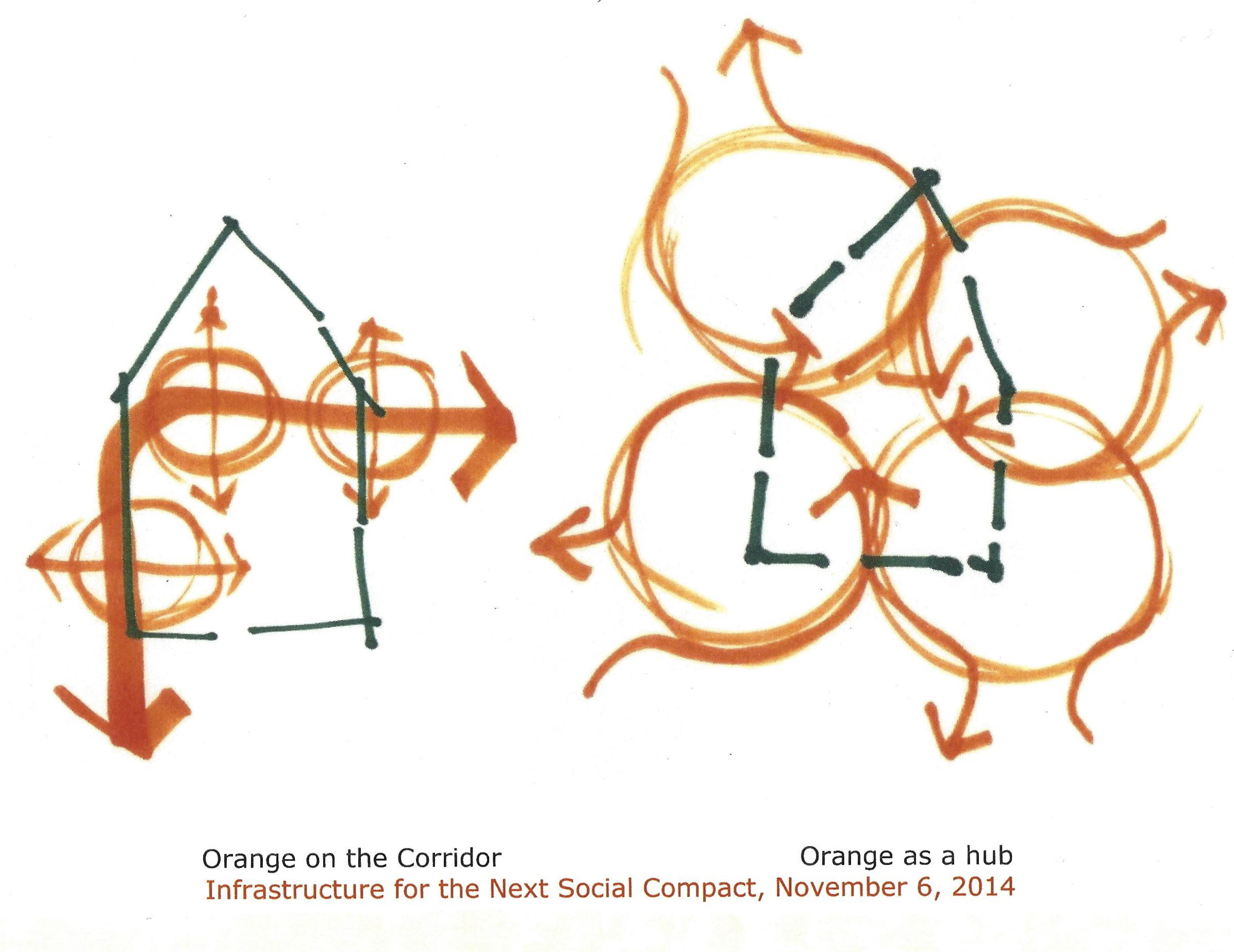

The role of the train line in the division of the city was revisited by William Morrish. He and his students helped us to understand that New Jersey was in the middle of a spurt of transit-oriented, “smart” growth that was pushing massive construction around train stations. In other cities, like Harrison, New Jersey, the new construction was completely unrelated to the historic city’s contents and form. A post-industrial city like Orange, Harrison was inhabited by working people who lived near the now-empty factories that once provided a good living. These were being bulldozed and replaced by luxury apartments for people who could take the train to work in New York City.

William Morrish—Orange as a “corridor” or as a “hub.”

“This kind of development,” Morrish told us, “focuses on a rail corridor and ignores the rest of the city. This will displace the poor and intensify the fracture that you’re trying to repair. What you want to help people understand is that there is a larger city to restore, there are many modes of transportation, and there is much opportunity for creating jobs in Orange so that people don’t have to commute. You have the opportunity to carry out a real and effective urban restoration, not this latest form of urban renewal.”

What we learned from Running Upstream

The Cities Research Group, deeply embedded in neighborhood systems, has lived this daunting process of repeated upheaval and documented its effects on populations. Public health is slowly coming to terms with the fact that downstream interventions are too small to make a difference and might even make things worse. As we move upstream—to examine larger systems and broader arenas of action—we will be looking more and more to partner with designers, ecologists, architects, urban planners, and others who share our profound concern for human life. Together, we can implement “magic strategies” that can undo past injustice and promote health for all.

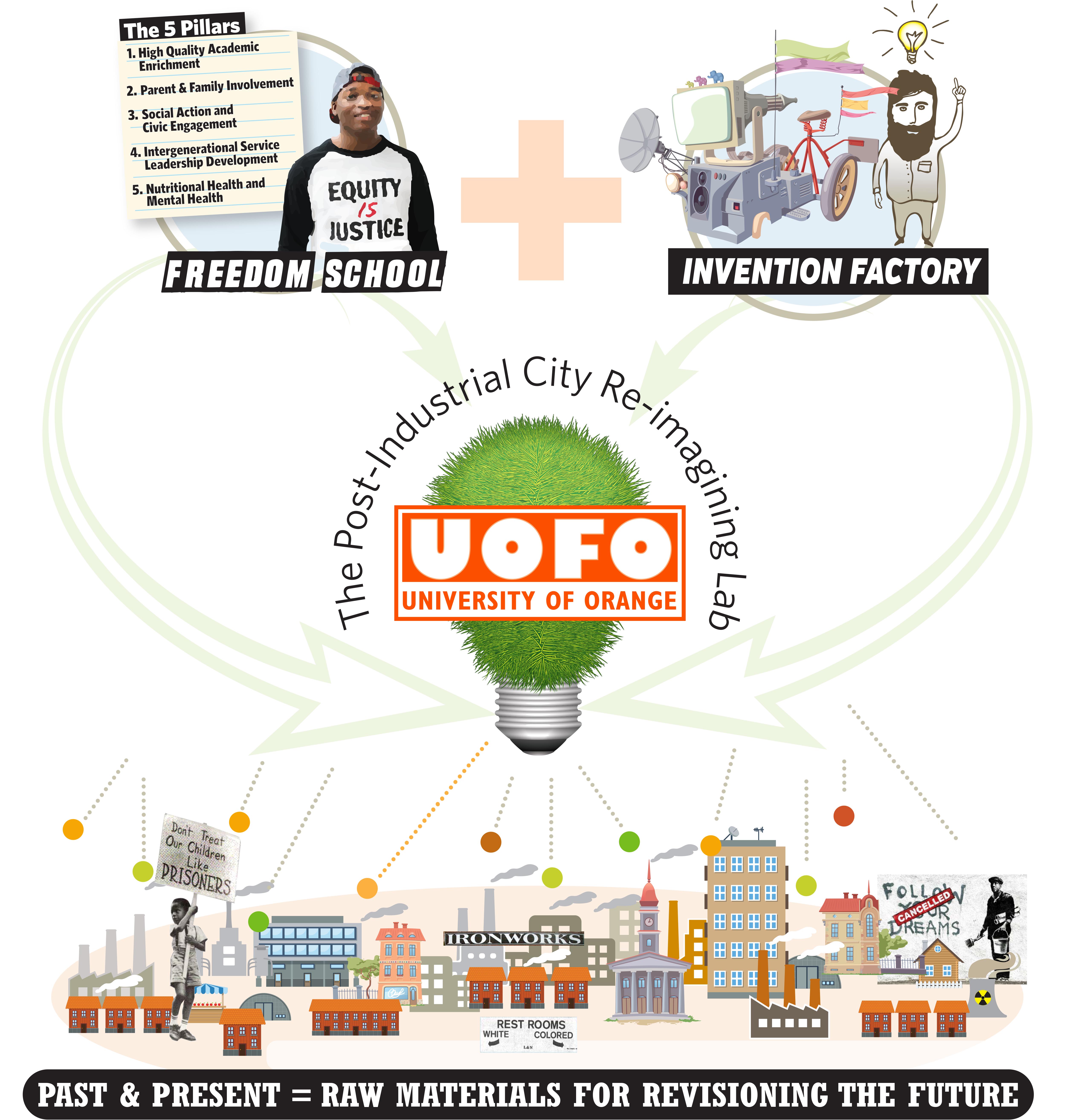

Post-industrial city reimagining lab poster by Pam Shaw to help us visualize the “mash-up” of the factory of invention and the Freedom Schools.