Examples of Chinese Ornament Selected from Objects in the South Kensington Museum and Other Collections (figure 1) was written by Owen Jones (1809-1874), one of the most influential English architects, designers, and design theorists of the nineteenth century. Jones selected 100 full-color plates sourced from the motifs of Chinese ceramics, cloisonné works, and carpet designs, and published them in 1867. In this book’s preface, Jones describes that these magnificent works of Chinese ornament had rarely been seen before the 1860s, “[and they] are remarkable, not only for the perfection and skill shown in the technical processes, but also for the beauty and harmony of the colouring, and general perfection of the ornamentation.”[1]

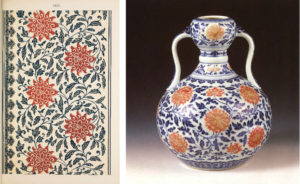

Figure 2. The Plate LIV from Examples of Chinese Ornament and A Fine Pair of Imperial Yellow-Ground Famille Rose Bowls

Figure 3. The Plate XLVII from Examples of Chinese Ornament and A Copper-Red-Decorated Blue and White Double-Gourd Vase

In his early design sourcebook for which he is known for best today, The Grammar of Ornament (1856), Jones used to have a much lower opinion of Chinese ornamental designs. He had thought that they had made only slight progress in a relatively long time. What was Jones’s motivation for changing his mind on Chinese ornament, and how did he find and put these exquisite plates into the book? During the vast political tumult in nineteenth century China, many of the finest examples of artworks from the Ming, Ch’ing and earlier dynasties were spirited out of the country and sold to Western collectors. In 1857, James Bruce (1811–1863) was appointed British High Commissioner to assist with opening China and Japan to Western trade. In 1860, during the Second Opium War (1856–1860), Bruce ordered the looting and destruction of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing (known as Yuanming Yuan). In the same year, Bruce’s secretary Henry Brougham Loch (1827–1900) seized a large amount of imperial treasures and in 1861 sold all the collections to Alfred Morrison (1821–1897), an English collector, who was known for his interest in Chinese artworks. Thus, it is no surprise that a large number of plates in the book were sourced from eighteenth and nineteenth century imperial collections; such as the pattern of plate LIV, which can be found at A Fine Pair of Imperial Yellow-Ground Famille Rose Bowls (figure 2), and the motif of plate XLVII depicting A Copper-Red-Decorated Blue and White Double-Gourd Vase (figure 3).

Apart from publishing seminal design sourcebooks, in 1851 Owen Jones also carried out the decoration of Joseph Paxton’s Great Exhibition building, The Crystal Palace, in Hyde Park. In 1863, he designed the Victoria &Albert Museum’s Indian, Chinese, Japanese courts, known as the Oriental Courts. From 1863 to 1867, Jones designed interiors for Alfred Morrison’s residences at Fonthill and 16 Carlton House Terrace.

[1] Owen Jones, Examples of Chinese Ornament Selected from Objects in the South Kensington Museum and Other Collections (London: S. & T. Gilbert, 1867), 3.

Weixin Jin is a graduate student in the Design History and Curatorial Studies program at Parsons / Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Jin is a researcher in the fields of Decorative Design and Museum Studies, and a lead author of Design Museum, which was published in 2014.

One thought on “Behind the History of Chinese Ornament”

Gail Byrt on July 6, 2019 at 5:39 pm

I have what I think is an Asian ornament it’s very heavy I have no idea where it’s come from let alone what it’s made of how can I find out