In the 1920s, architect Hector Guimard, a pioneer of the stylized natural forms and curving lines of late 19th century Art Nouveau, turned his attention to socially conscious design as France struggled to recover from the widespread devastation of the First World War.

The impact of the “Great War” on French infrastructure, agriculture and housing was overwhelming, with over 17,000 public buildings and more than 500,000 homes damaged, in addition to destruction of hundreds of miles of roads and railway tracks and millions of hectares of agricultural land.[1] The loss of so many dwellings fueled a housing crisis that was felt most strongly in Paris and the surrounding suburbs to which so many had fled during the war, not only to escape the encroaching German army but to find work in the war industries in the Department of the Seine. Housing construction had essentially stopped during the war years, thus the unplanned urban sprawl in these suburbs, characterized by high-density, unsanitary dwellings, became inundated with people for whom there were few other options.

While affordable housing had always been a problem in Paris, it was, without question, intensified by the war. Before 1914, groups like the Société du Nouveau Paris and the Société Français des Logements Hygiéniques à Bon Marché encouraged architects to expand their activities into the everyday matters of civic infrastructure and housing. After the war, and with the encouragement of public officials, these efforts were redoubled. In 1921, Hector Guimard, Frantz Jourdain, Henri Sauvage, Louis Süe and other high-profile French designers and architects founded the Groupe des Architects Modernes, a consortium which aimed to rebuild the devastated rural areas in addition to designing new mass housing projects and working cities.[2]

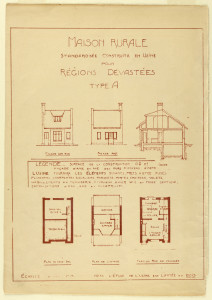

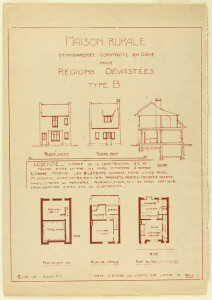

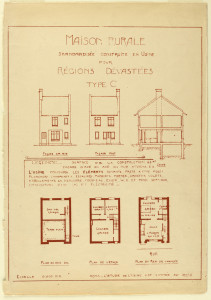

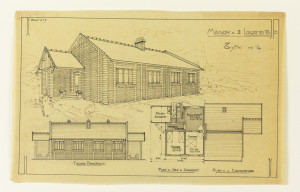

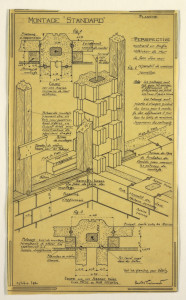

One of Guimard’s first forays into standardized housing was a series of three “factory built” rural houses designed for régions dévastés (devastated regions) in 1920. A hand-written notation on the plan sets the stage for his later experiments in serialized design, stating:

The factory will forge the following elements, ready to be laid: floorboards, frames, stairs, doors, shutters, carpentry and woodwork, stove, sink, W.C. and septic tank, pipes for water and gas, and electricity.

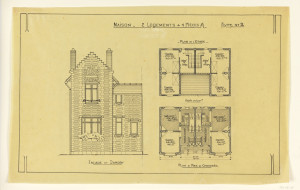

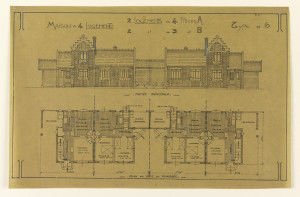

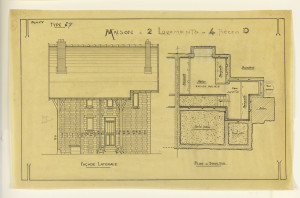

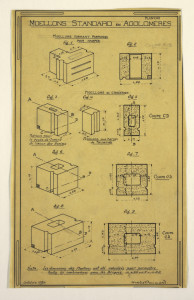

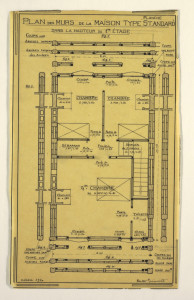

A few years later, Guimard designed a larger series of eight distinct dual-family houses to accommodate families of differing sizes. Donated to Cooper Hewitt by his widow shortly after his death, the building plans, accompanied by dozens of detailed sketches, reveal that Guimard intended to use prefabricated, modular components to ensure that the construction of these much-needed dwellings would be fast, simple, and affordable. These plans, which relied on his ingenious system of dry concrete block construction, also utilized standardization in the interior design, from larger elements like doors, windows, fireplaces, and appliances, to the smaller, more decorative features on the exterior, including decorative bricks and simplified variants of Guimard’s cast-iron railings.

While Guimard is best known for the Castel Béranger and other highly individualized, large-scale apartment buildings and hôtels particuliers that typified the Art Nouveau aesthetic, these designs for affordable housing reflect the new spirit of French architects and designers during the interwar period, characterized by experiments with affordable materials and a focus on socially conscious design and urban planning. It is unknown if these designs ever came to fruition; though he erected several apartment buildings in the early 1920s and participated in the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs in Paris with the Groupe des Architectes Modernes, Guimard completed few architectural commissions in the 1930s. In 1938, admist rising tensions across Europe, Guimard and his wife, the Jewish-American painter Adeline Oppenheim, immigrated to New York City where he died just four years later.

Visit the Learning Lab to see more drawings from this series.

[1] Lothar Kettenacker and Torsten Riotte, The Legacies of Two World Wars: European Societies in the Twentieth Century (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011), 120.

[2] Anthony Sutcliffe, Paris: An Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 151.

Ria Murray is a graduate student in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered jointly by the Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is a Fellow in the museum’s Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department.