In last month’s Cooper Hewitt Short Story, the exuberant personality of Robert Winthrop Chanler unfolded in a large gift of illustrated books to Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library. May’s Short Story celebrates the curatorial vision that brought a professional edge to the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, that of Calvin Hathaway.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

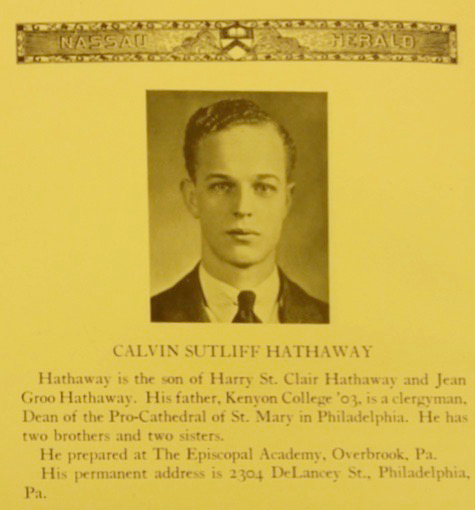

May 2017 marks the 120th anniversary of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt officially opened the doors of the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration—now Cooper Hewitt—in May 1897. This short story honors their vision, reinterpreted and modernized for over thirty years by Calvin S. Hathaway (1907–1974). Hathaway was the first professional art historian at the Cooper Union Museum. He became its director after his return from military service as a Monuments Man in World War II.

Hathaway graduated from Princeton University in 1930, majoring in French literature. After Princeton, he continued art history studies at Harvard and New York University and began his curatorial career at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1933, Hathaway was hired as assistant curator at Cooper Union Museum by curator Mary S.M. Gibson.

Calvin Sutliff Hathaway, 1930. Collection of Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University Library.

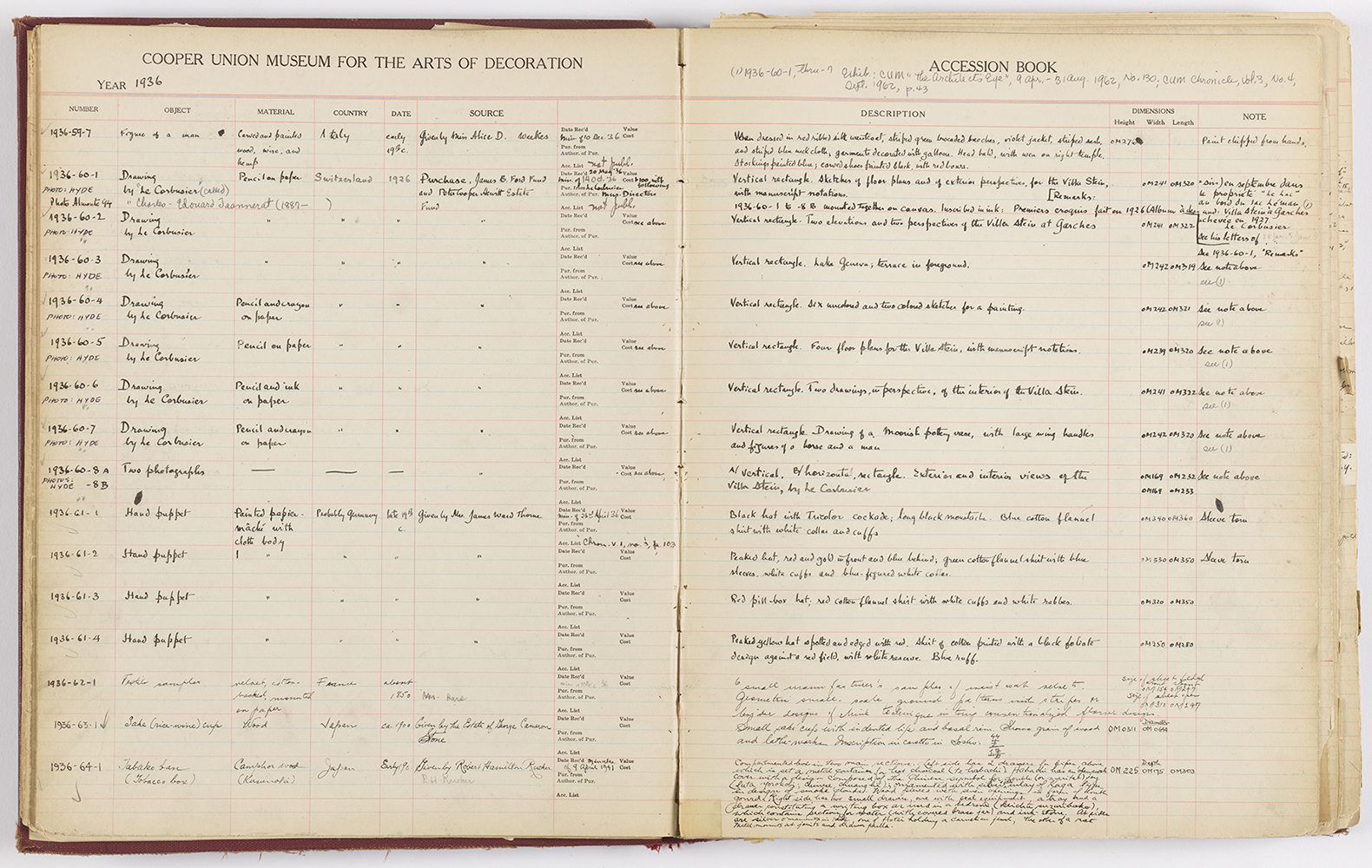

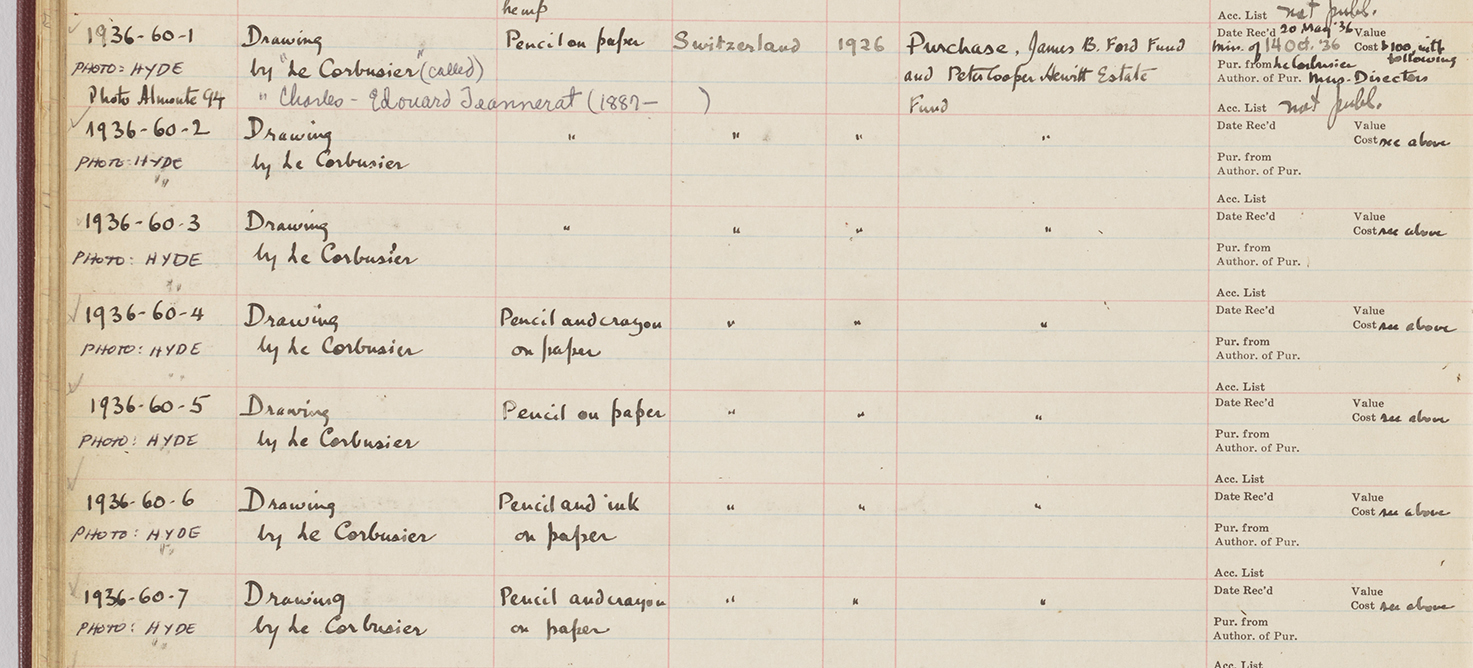

Hathaway methodically undertook to modernize the museum, beginning with organizing a system of cataloging all the objects received by the museum since its founding forty years prior. This system of classification—assigning each object an accession number—was later used as a basis for indexing looted works of art recovered in Germany during and after World War II.

Page from Cooper Union Museum Accession Book showing the 1936 purchase of Le Corbusier drawings and photographs for the Villa Stein, with notations by Hathaway. Eager to collect drawings by contemporary architects and designers, Hathaway purchased these for $100, the first works by Le Corbusier to enter an American museum.

Detail of the above page showing the purchase of drawings by Le Corbusier.

Former Curator and Head of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Gail Davidson wrote about the Villa Stein studies, which had been commissioned by Gertrude Stein’s brother, Michael.

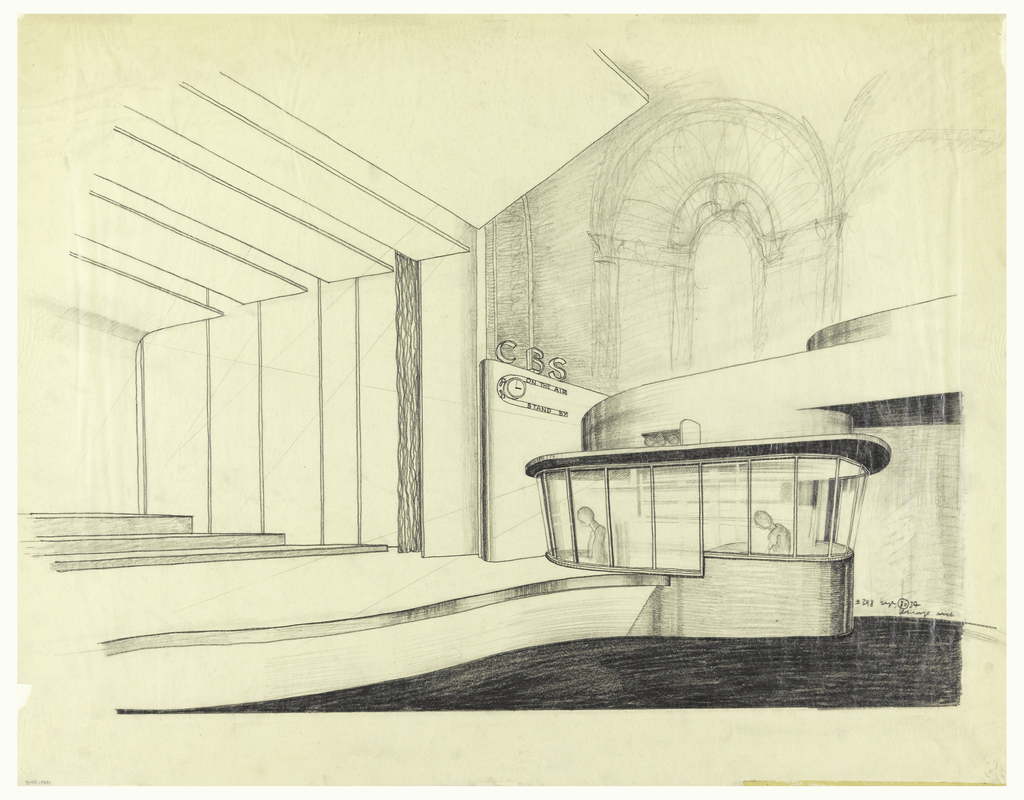

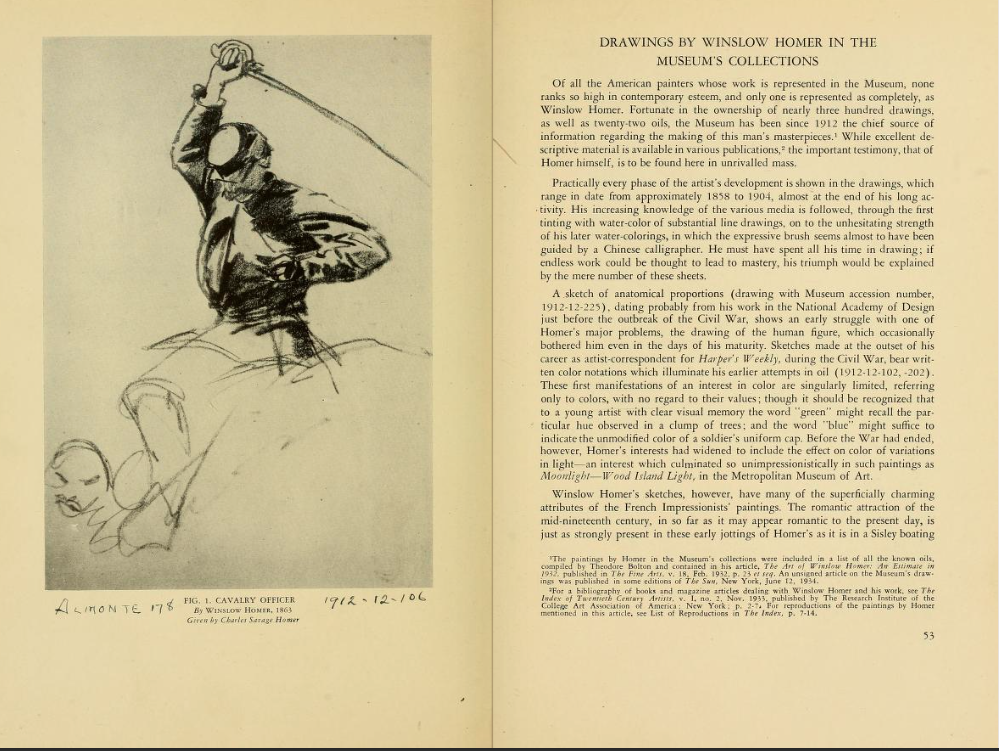

Hathaway inaugurated changing exhibitions of objects in the museum’s collections. In 1935 he introduced the Chronicle of the Museum for the Arts of Decoration of Cooper Union, an annual scholarly publication devoted to collections and exhibitions. The first issue included articles on historic printed fabrics and French silver as well as “Contemporary Architecture,” a loan exhibition representing the work of eighteen architects, among them William E. Lescaze. Hathaway’s article about Winslow Homer in the second issue was the first published piece on Homer’s graphic art.

Chronicle of the Museum for the Arts of Decoration, Volume 1, 1935–45, and Volume 2, 1949–58, can be accessed through Smithsonian Libraries.

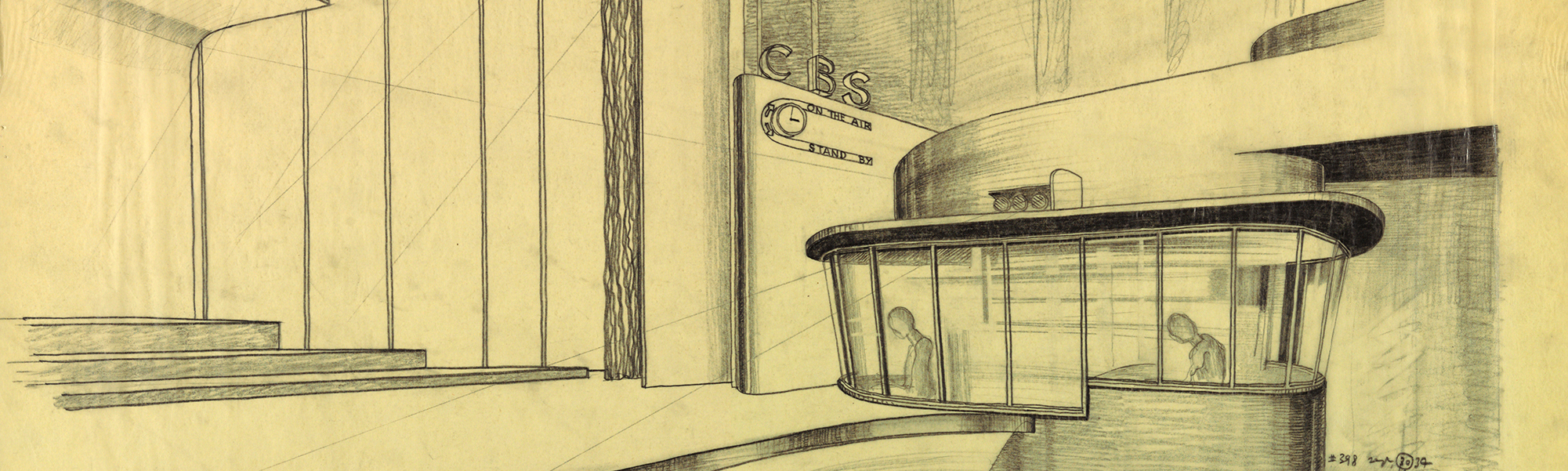

Drawing, Design for Alteration of the Avon Theater, 1934; Designed by William E. Lescaze (American, b. Switzerland, 1896–1969) for Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) (New York, New York, USA); Graphite on white tracing paper; Gift of William E. Lescaze, 1937-37-5. This drawing is currently on display at Cooper Hewitt in the exhibition World of Radio.

“Drawings by Winslow Homer in the Museum’s Collections,” by Calvin S. Hathaway. Chronicle, vol. 1, no. 2, April 1936.

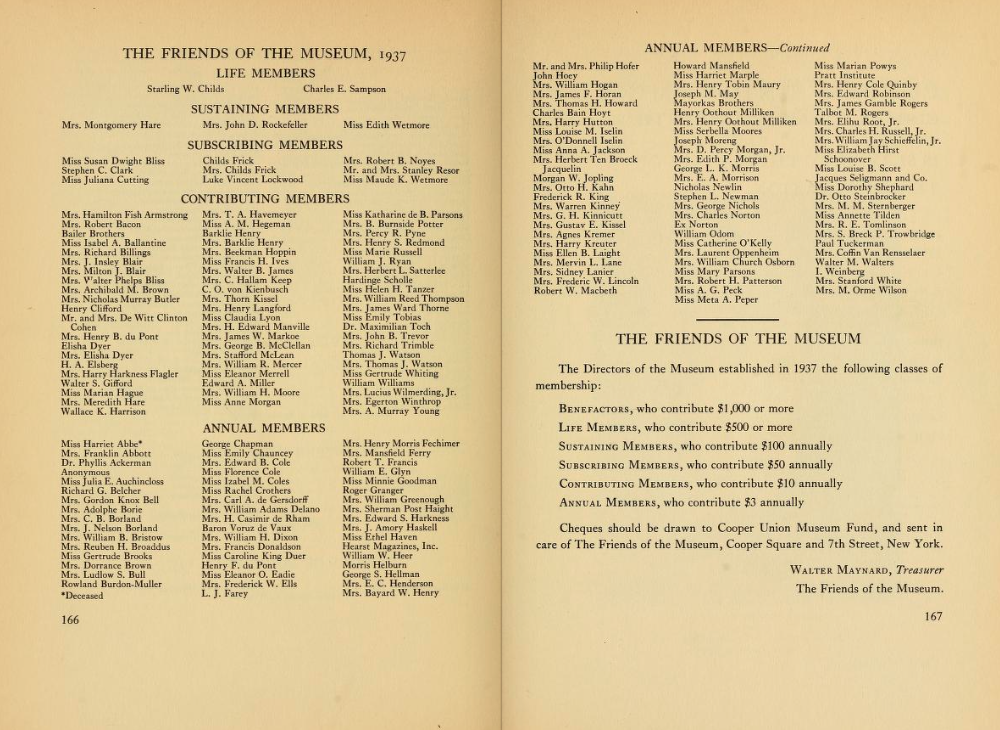

Hathaway established a support group called the Friends of the Museum in 1934. Members, many very prominent, were listed annually in the Chronicle, along with acknowledgments of donors to the museum and its library. This initiative was very successful and membership grew significantly over the years. Additionally, volunteer workers were acknowledged for their service.

The Friends of the Museum, Page from the Chronicle, 1937.

Set of playing cards from the Cooper Union Museum, 1950s, featuring a Venus and Cupid brooch and pendant and another pendant. Could these cards have been a gift of membership?

Hathaway also built a staff of “keepers” (curators) of the collections. These accomplishments were extraordinary—and all before 1942, when he took a leave of absence from the Cooper Union and enlisted in the United States Army.

Captain Calvin S. Hathaway (left) and Benvenuto Cellini’s La Saliera (right). Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art.

In December 1943 Hathaway was assigned to the Army’s newly created Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA), working in a branch of the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), German Country Unit. Hathaway authored the Civil Affairs Handbooks for Germany and Austria and completed the Official List of Monuments. As a Monuments Man he joined a group of nearly 350 museum directors, curators, archivists, and art historians—men and women from fourteen nations. Hathaway worked closely with Captain James Rorimer (Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1955–66) in Germany to recover tens of thousands of looted works of art and cultural objects. In Kitzbuhel, Austria, he is credited for recovering and identifying a cache of art stolen from the Vienna Kunsthistorische Museum, including Benvenuto Cellini’s gold salt cellar, La Saliera. For participating in some of the most memorable recoveries achieved by the MFAA, Captain Hathaway was awarded the Bronze Star in 1945.

After the war, Hathaway resumed his duties at the Cooper Union Museum, but he faced many challenges. Alice Beer, who came to the museum in 1948 as “keeper” in the textile department, wrote of these years:

“In 1948 the Third Avenue El thundered along the east side of the building; the alcoholics clustered in the shade or lay sodden below the statue of Peter Cooper. The ‘nice people’ had moved uptown. Visitors to the museum came with a purpose . . .”

South from Cooper Union, May 1955. Photograph by Calvin S. Hathaway. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York. The Third Avenue El was demolished by late 1955. Hathaway photographed the progress of the dismantling over many months.

“It was a small, crowded Museum, crowded with treasures but adherent to the Hewitt sisters wish that there be unrestricted use of objects” (Alice Beer). There was little working space, and Hathaway and his small staff doubled in many roles. The library, always busy, was open two evenings a week. Hathaway personally contributed many hundreds of books to the library. In 1958, there were over 85,000 objects in the museum collection; the library had 13,000 volumes and 750,000 classified illustrations.

Hathaway and his staff planned theme exhibitions in the 1950s that were “immensely clever, original and beautiful” (Alice Beer). Spaces in the museum were rearranged with special cases designed to showcase collections and attractive new lighting was added.

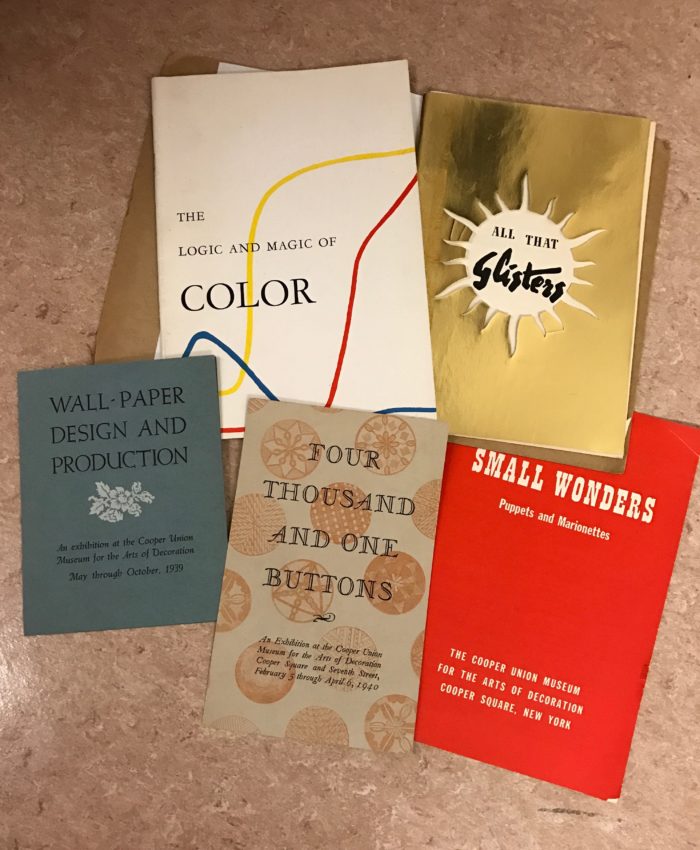

Cooper Union Museum Exhibition catalog covers: All that Glisters, Small Wonders, Four Thousand and One Buttons, Wallpaper Design and Production, The Logic and Magic of Color. Courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library.

Unfortunately (you knew this was coming), Cooper Union’s interest in maintaining the museum gradually deteriorated. During the 1950s, friction between the museum and the Cooper Union grew. Needs of Cooper Union’s Schools of Architecture and Engineering began to take precedence. Museum finances and upkeep became a major issue along with questions about how the museum was broadening its audience. The primary audience was largely design students and professionals, as the museum location on the fourth floor of the Cooper Union made it difficult for casual visitors.

Hathaway showing objects from the museum’s textile collections to Cooper Union engineering students. From Cooper Union in Action (1945), a set of marketing images from the Architecture Archive at Cooper Union.

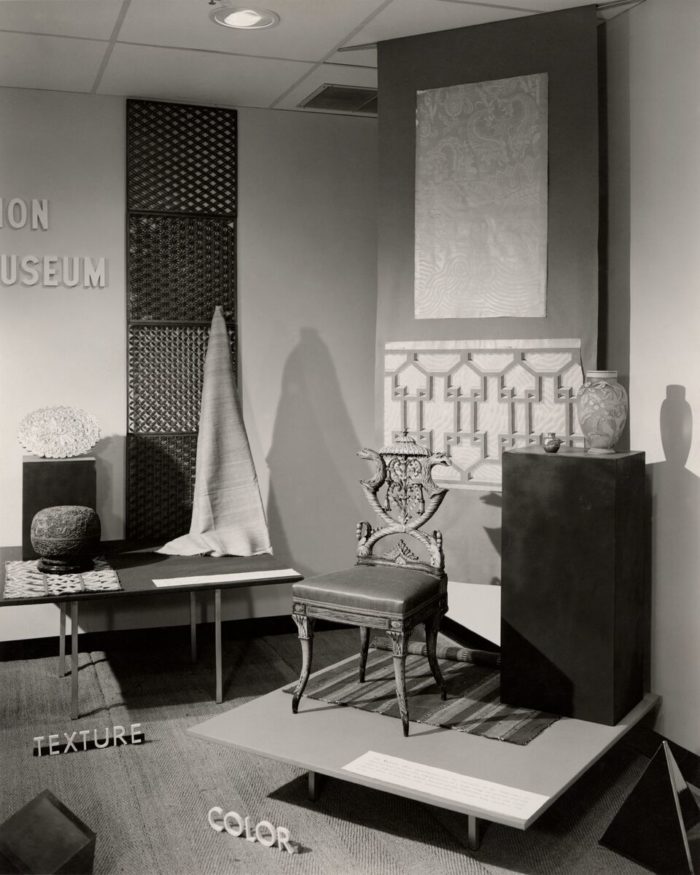

Hathaway attempted to meet the challenge with new exhibitions focused on concepts of the essential elements of design—form, color, texture, line. These exhibitions featured both historic and modern objects. The Logic and Magic of Color and The Elements of Design were widely praised, and looked back to Peter Cooper’s purpose in founding Cooper Union as a free school for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Design Installation, Cooper Union Museum, 1958. The chair pictured is currently on view at Cooper Hewitt in Hewitt Sisters Collect.

Detail of section on color designation and color symbolism in the exhibition The Logic and Magic of Color, 1960.

In June 1963, Cooper Union Trustees announced the study of plans for the possible discontinuance of the museum and the relocation of the museum collections. Calvin S. Hathaway announced his resignation in August 1963. After thirty years at the Cooper Union Museum, he returned to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as the R. Wister Harvey Curator of Decorative Arts, a position he held from 1964 to 1972.

Curator and author David A. Hanks remembers Hathaway after he had retired from the Philadelphia Museum of Art:

“He was a perfectionist and very knowledgeable about the entire history of European and American decorative arts. . . . A gentleman of the old school—very formal . . . He loved French eighteenth century, but he was also fascinated with the Victorian period and modern design. . . I only wish I could have worked for him, as I would have learned a great deal.”

Image, Calvin Sutlff Hathaway, from Recent Acquisitions by the Cooper Union Museum; a Picture book in honor of Calvin S. Hathaway, by Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, 1964.

The Cooper Union Museum became a unit of the Smithsonian Institution in 1968. The Smithsonian acquired the Carnegie Mansion as the new home for the newly named Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Design.

SOURCES

Beer, Alice B. Cooper Union Museum to Cooper-Hewitt Museum: Draft of a History of the Continuation of “The Making of a Modern Museum,” March 1977. Smithsonian Ar-chives, Record Unit 547.

“Designed for Use,” Museum News, Vol. 39, No. 6, March 1961.

Keslacy, Elizabeth M. “The Architecture of Design: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (1896-1976)” (PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, 2016).

Lynes, Russell, More Than Meets the Eye. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1981.

Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art. “Calvin Sutliff Hathaway.” http://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org/the-heroes/the-monuments-men/hathaway-capt.-calvin-s.

Minutes of the Cooper Union Museum Advisory Council, 1930-1963. Registrar’s Office, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Nicholas, Lynn H. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Knopf, 1994.