Textiles by Peche can been seen in the exhibition The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s, now on view through August 20, 2017.

When the Austrian designer Dagobert Peche died on April 16, 1923, Josef Hoffmann, one of the founders of the Wiener Werkstätte, proclaimed: “Not even every hundred years, at most perhaps every three hundred years, does a country see the birth of such a genius. Dagobert Peche was the greatest ornamental genius Austria has produced since the Baroque…. All of Germany has arrived at a new stylistic epoch thanks to Peche’s patterns.”[1]

Peche designed over 110 different fabric patterns for the Wiener Werkstätte from 1911, when he started his collaboration with the textile department, until his death twelve years later.[2] His preeminence as a designer included other textile-related areas such as lace, embroidery, and beading, and extended to designs for interiors, glass, furniture, ceramics, and wallpaper. By 1915, when he officially became a member of the Werkstätte, he was already the chief designer for its wallpapers.

The Wiener Werkstätte was the idea of designers Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser and their friend, the industrialist, Fritz Wärndorfer, who in 1903 wanted to establish an alliance of artists and craftsman based on the ideas of the Englishmen John Ruskin and William Morris. Officially registered as the Wiener Werkstätte-Produktiv-Gemeinschaft von Kunsthandwerkern in Wien (Viennese Workshops Craft Workers Association ), its aim was to elevate applied arts to the fine arts and to promote its members’ financial interests through schooling and training in the applied arts, and through the establishment of workshops (metalwork, ceramics, textiles, glass, graphic arts, fashion, jewelry, architecture, interior design, and furniture) to create objects for sale.

In the early years of the Wiener Werkstätte there was a strict adherence to more geometric patterns and forms with Hoffman and Moser as examples, but by 1915 Peche had changed the course of the workshop to embrace both naturalistic and fantastical ornamentation. For Peche, utilitarian objects became a surface for decoration.

Regenbogen (Fig. 1) (Wiener Werkstätte no. 653) was introduced in 1919 and was available in a variety of colorways—blues, purples, reds, grays—and almost limitless shading combinations within each color. Unlike the stark graphic quality of his posters, Peche’s textiles have a more subtle and refined color sense. The ombré effect in Regenbogen, for example, where shades of color melt into each other, resulted from a type of block printing. Ink colors were spread in shaded bands by a brush or roller and then picked up with blocks by the printer, who transferred them to the cloth. It was almost impossible to detect the seams of the block or any printing flaws when using this technique.[3]

Block printing was the preferred printing technique in the textile department. Like other hand-crafted objects offered by the workshop, these textiles were quite expensive to produce, especially when using more complicated techniques as with Regenbogen. Only the wealthier clientele could afford most of the Wiener Werkstätte designs.

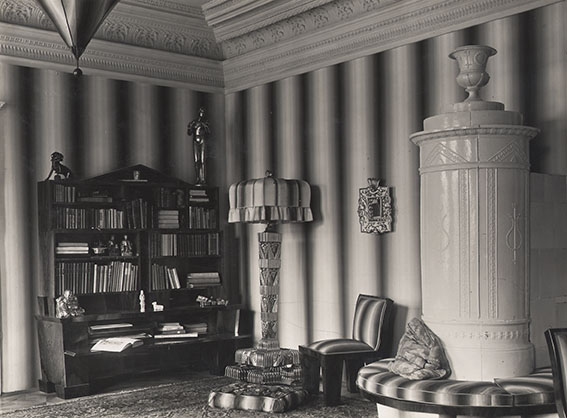

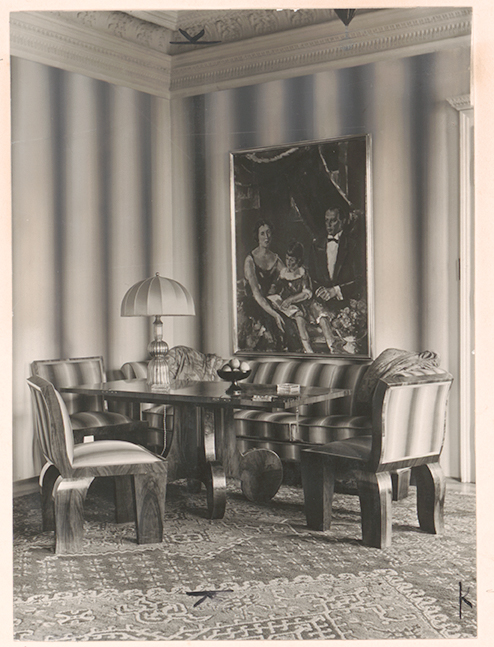

One of these individuals was Wolko Gartenberg who commissioned Peche in 1921 to design an apartment interior—workroom and living and dining rooms (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Peche used Regenbogen for virtually every surface that could be covered with a fabric—walls, chairs, cushions, and lampshades. Even the exquisite graining of the furniture, also designed by Peche, had a similar striped sensibility to Regenbogen. Peche’s passion for ornamentation and pattern resulted in a spectacular living environment in which every solid structure—from the furniture to the walls—transformed into pulsating stripes.

Figure 2: Photograph, Wolko Gartenberg apartment: Corner seating in the living room, 1921, MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art

Figure 3: Photograph, Wolko Gartenberg apartment: Living room, 1921, MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art

Peche designed variations of the Regenbogen pattern often with bold floral motifs on top of the ombré striped patterns as if to underscore that the stripe itself was a plain ground to receive another layer of ornamentation. The textile was also used in the context of fashion and applied to textile corsages, handbags, and garments. Peche was extraordinarily prolific during his years at the Wiener Werkstätte, a testament to his total commitment to the applied arts as conceived by the organization. In Peche’s compilation of writings, titled “The Burning Bush” (1922), he laid out his thoughts about aesthetics, the relationship between art and technology, and the future of the Wiener Werkstätte. He wrote with a clear understanding about the need to expand the commercial ventures of the Wiener Werkstätte. At the same time, he maintained his prescient vision of the Wiener Werkstätte as a “culture emporium of the twentieth century. . . . It is the department store in the best sense of the word. . . . It is the fine-art department store, the emporium of humanity.”[4]

This essay is excerpted from the book Making Design, available through SHOP Cooper Hewitt.

[1] Berta Zuckerkandl, “Errinnerung an Dagobert Peche,” Neues Wiener Journal (April 19, 1923), quoted in Anne-Katrin Rossberg, “Who is Peche?,” in Dagobert Peche and the Wiener Werkstätte, ed. Peter Noever (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 30.

[2] This amounted to about ten percent of the printed and woven designs over the course of the Wiener Werkstätte (1903–32), with approximately one hundred artists responsible for designing over 1,800 patterns.

[3] Anne-Rose Bringel, conservator at Museum of Printed Textiles, Mulhouse, France, e-mail message to author, August 5, 2013.

[4] Dagobert Peche, “The Burning Bush,” 1922, quoted in Dagobert Peche and the Wiener Werkstätte, ed. Peter Noever, trans. Russell Stockman (New York: Neue Galerie, 2002), 187.