Author: Aaron McIntosh

September is New York Textile Month! In celebration, members of the Textile Society of America will author Object of the Day for the month. A non-profit professional organization of scholars, educators, and artists in the field of textiles, TSA provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of information about textiles worldwide.

The United States’ most recent election cycle saw a bevy of political textile messages. Most prominently, there was Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” bright red baseball cap, which was countered by feminist activists with hot pink knitted “Pussy Hats”. For the past three decades, politics has been all about branding, and what better medium for your message than the flexible, widely distributable and easily co-opted mass-produced textiles?

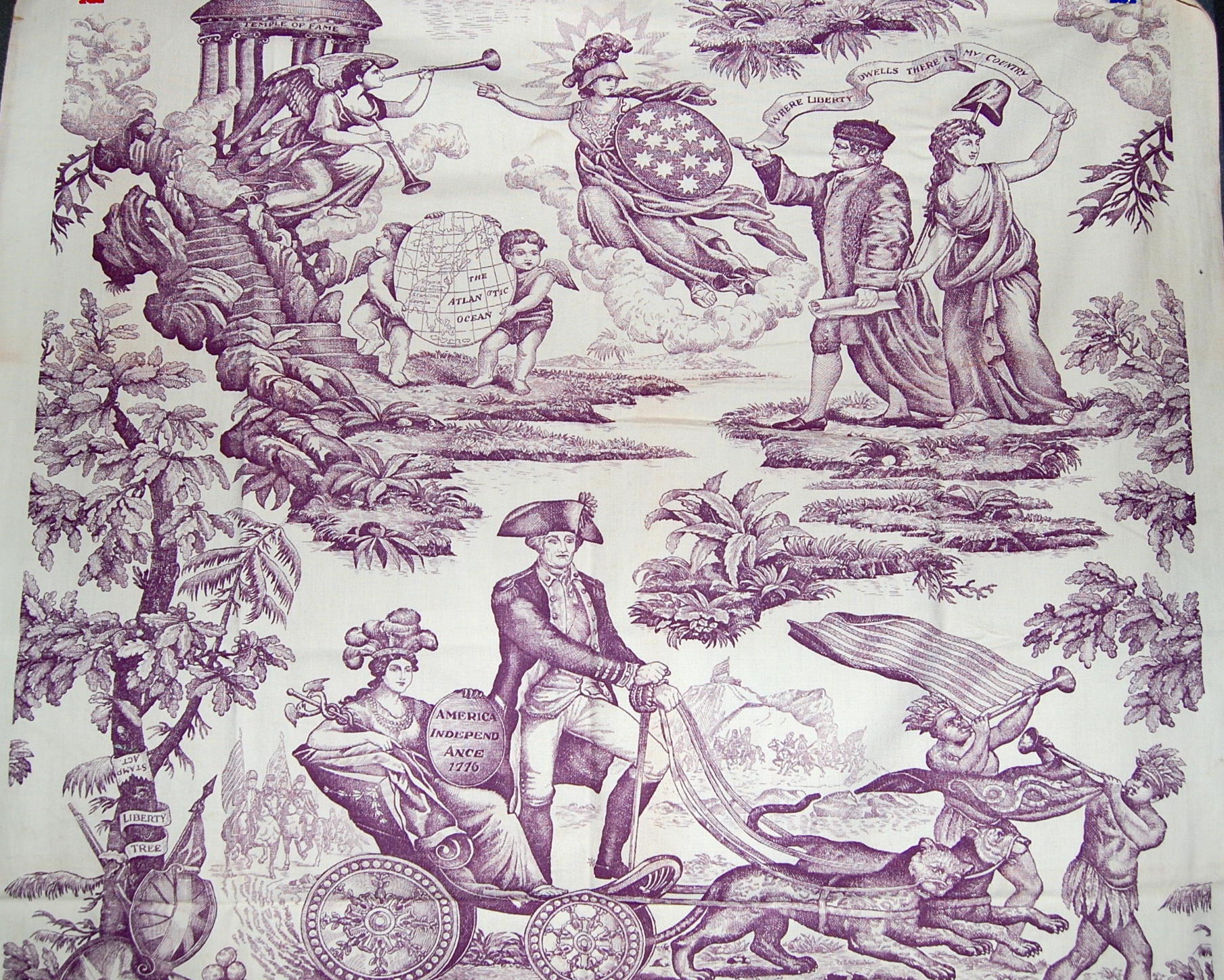

The history of printed political cloth is a long and storied one: flags declaring the conquering of a foreign power, bunting used to display patriotism, fashion dictates of power-holders the world over, and screen-printed protest banners. Perhaps no other Western textile is more closely aligned with politics, nationalism, colonialism and society than the famous toiles de jouy. Mostly depicting idyllic scenes of leisure or pastoral farming, the medium was also heavily used for political and allegorical purposes. In the early years of the American Revolution, yardage such as The Apotheosis of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin (1785) was mass-produced in France and distributed to the Yankees, who used it as anti-British rally bunting. Here is a definition of apotheosis

Eisenhower was wooed by both Democrats and Republicans to run for their party in the 1952 campaign. A much-celebrated WWII hero and a moderate conservative, Eisenhower was one of the most popular presidents elected in the 20th century. He increased social safety-net programs like Social Security, and continued New Deal poverty initiatives. He redefined nationalism after WWII, and put Americans to work on massive infrastructure projects, most notably the country’s first interstate highway system.

Eisenhower Toile, “styled” by famous interior decorator Elisabeth Draper, celebrates the notable guideposts of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s military and civilian life. In the grand tradition of the French toiles de jouy, using the history vignette style, Draper embedded images of the West Point, Columbia University, The White House, and Eisenhower’s homes at Abilene, Texas; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; and Denver, Colorado. Other medallions include United States national symbols, a Republican elephant, and arrangements of military trophies and “pillage piles” of Nazi weapons and captured swastika flags. This odd mix of presidential sites, national symbols and grotesque emblems of war is forced into cohesion with a Baroque framing of flowers, palms and oak leaves—contrasting symbols of America’s compassion, beauty and self-styled nobility.

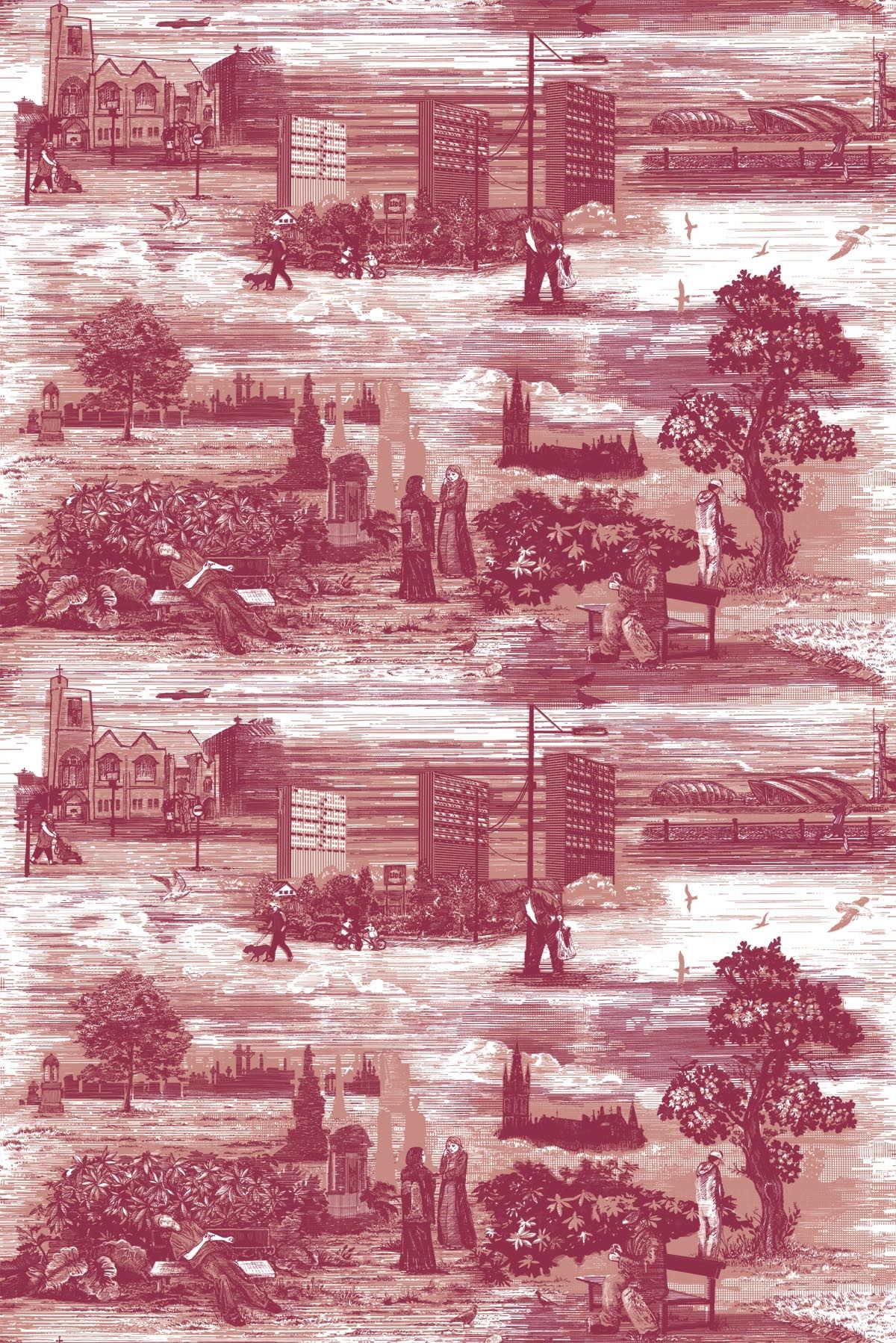

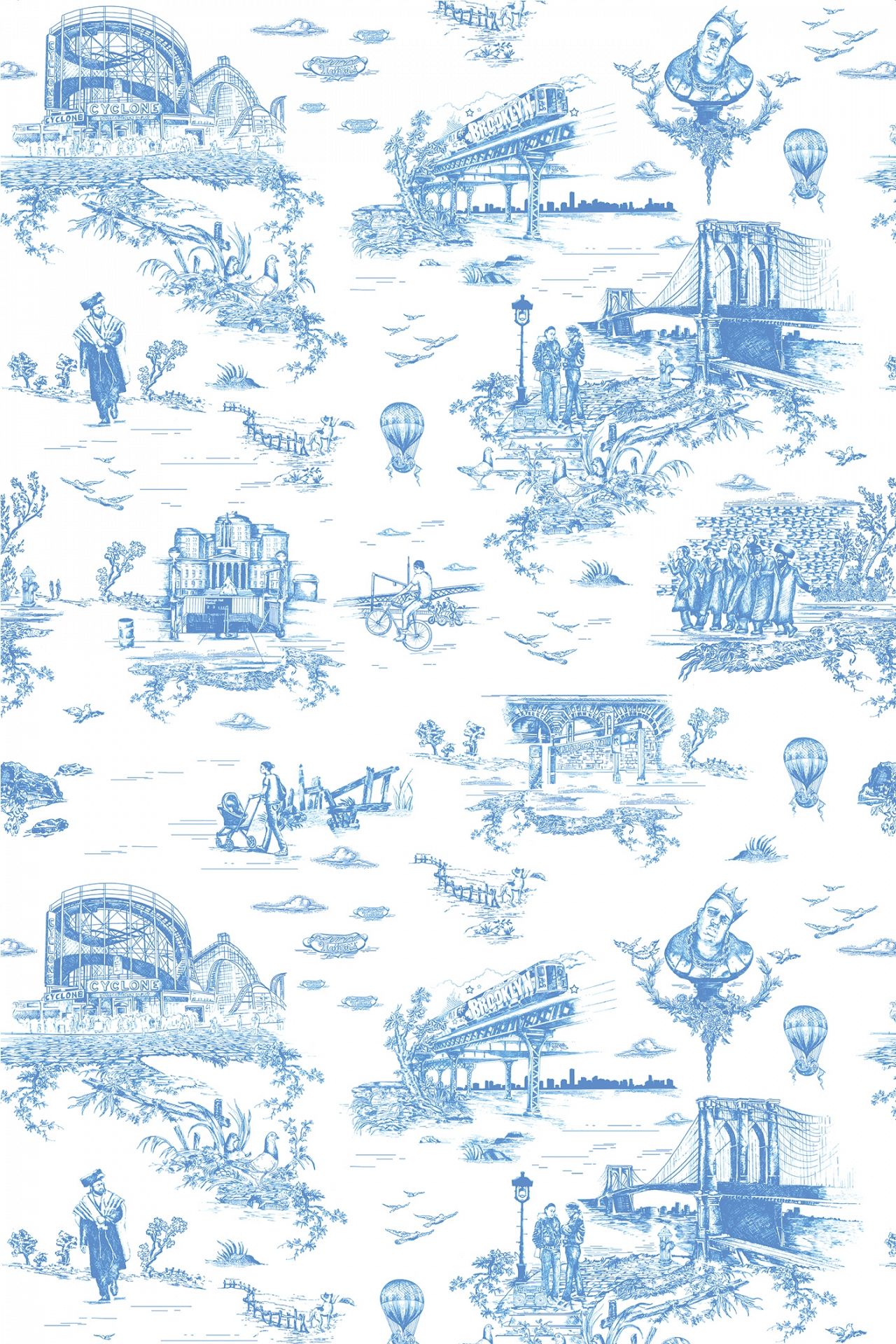

Toiles have a mysterious decorative draw that has kept them in production for over three hundred years, despite their heyday lasting roughly from the 1750s to 1890s. Toiles found a patriotic-tinged resurgence in America in the 1930s with the renovation of Colonial Williamsburg, and were increasingly common leading up to the 1976 Bicentennial. Since the mid-2000s, we have seen yet another revival of toiles, this one more subversive. Timorous Beastlies’ Glasgow Toile features mis-en-scenes of urban plight, such as a heroin user and a mugging. Contrast the Brooklyn-based Flavor Paper company, which produces a Brooklyn Toile, “capturing the King’s borough from Coney Island to Hasidic Jews to Notorious B.I.G. to our own Boerum Hill. Daily life in the bk dealing with subways, pigeons, b-boys makin’ the freak freak and stroller moms.” [1]

Timorous Beasties, Glasgow Toile

Flavor Paper, Brooklyn Toile

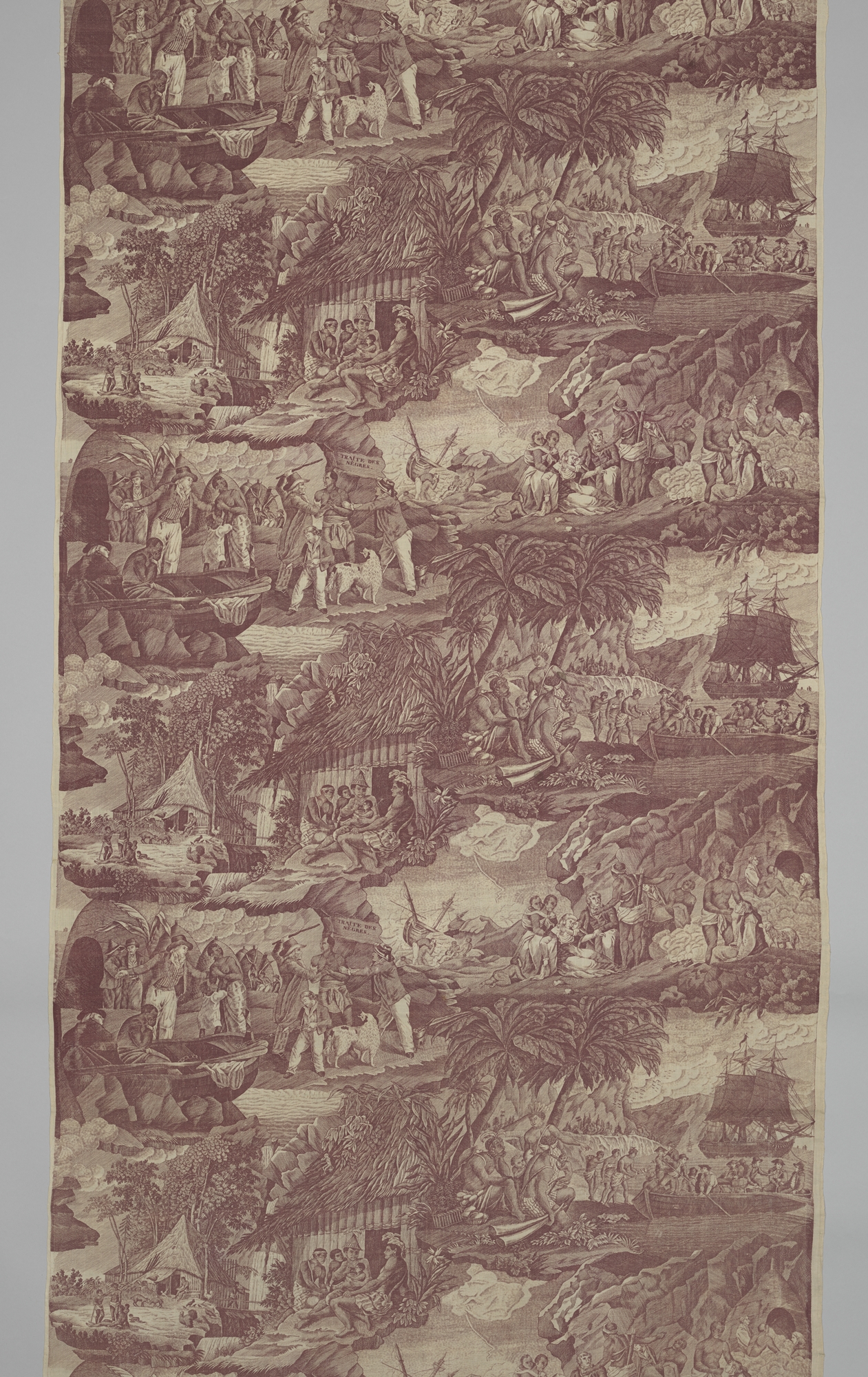

And before you write them off as exclusively Euro-centric, conquest oriented, and politically incorrect, consider the toiles of abolitionist Frederic Feldtrappe in early 1800s France. His Traite des Nègres (The Slave Trade) depicts four narrative scenes: “Two contrast the brutality of European slave traders with the kindness of Africans who minister to a shipwrecked European family. The other two scenes juxtapose a happy African family with the appearance of European traders in Africa. Their cache of trade goods (including textiles) ominously foreshadows the horrors of the traffic in human beings.” [2]

Frederic Feldtrappe,, Traite des Nègres

Given these times of growing civic insecurities, this blogpost is a charge, a challenge to young designers to bring this textile tradition into the contemporary political fray. Give us an Apotheosis of Deray Mckesson, Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, Patrisse CullorsLaverne Cox, or _______.

[1] Flavor Paper website. “Brooklyn Toile statement.” Designed by Mike Diamond & Vincent J. Ficarra/Adela Qersaqi of Revolver New York. (Date unknown)

[2] Object listing: Traite des Nègres (The Slave Trade). Interwoven Globe Exhibition. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2014. http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/view?exhibitionId=%7b063a1aa2-5a4e-439a-a332-046e00e8bd73%7d&oid=221809&pg=0&rpp=100&pos=114&ft=*

Aaron McIntosh is a fourth-generation quiltmaker and contemporary artist who works in textiles, sculpture, drawing, collage, and photography. His work has been exhibited widely, and most recently in “Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community” at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in NYC. He lives and works in Richmond, VA, where he is an Assistant Professor in Virginia Commonwealth University’s Craft/Material Studies Department.

One thought on “A Toile for Our Times”

Susan Goodwin on November 2, 2017 at 7:49 pm

Very interesting. Thank you. I learned a lot. But once again I’m frustrated by not being about to magnify the images so I can see detail.