In last month’s Cooper Hewitt Short Story, wallcoverings curator Greg Herringshaw introduced different styles of wallcoverings collected by the Hewitt sisters that are now housed in Cooper Hewitt’s expansive collection. This month, Forrest Pelsue, publishing master’s fellow in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies at Parsons Paris, takes us on a journey to 1939 to explore the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration through a newly discovered cache of gallery photographs.

Written by Forrest Pelsue

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

A Trip to the Past

The year is 1939. The United States is coming out of the Great Depression while Europe sinks back into international conflict. Bread costs 8¢ a loaf, The Wizard of Oz has just debuted in Hollywood, and the New York World’s Fair is underway. Between the economic upswing, tensions abroad, and enclosing isolationism, it is an interesting time to be an American. Since travel to Europe is becoming a rather dangerous undertaking, the best way to explore artistic and cultural history is with a visit to a museum. And when it comes to the decorative arts, the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (the collection of which is now housed at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum) is the place to go.

Let’s a take trip to Astor Place in New York City and browse the collection as it was installed in 1939. On our way, we can consider how the museum acted as a space for the study of decorative arts that would have been otherwise inaccessible to many Americans at the time. We’ll also see how the display of decorative arts has changed since the early twentieth century and try to imagine what it would be like to visit the museum of the past.

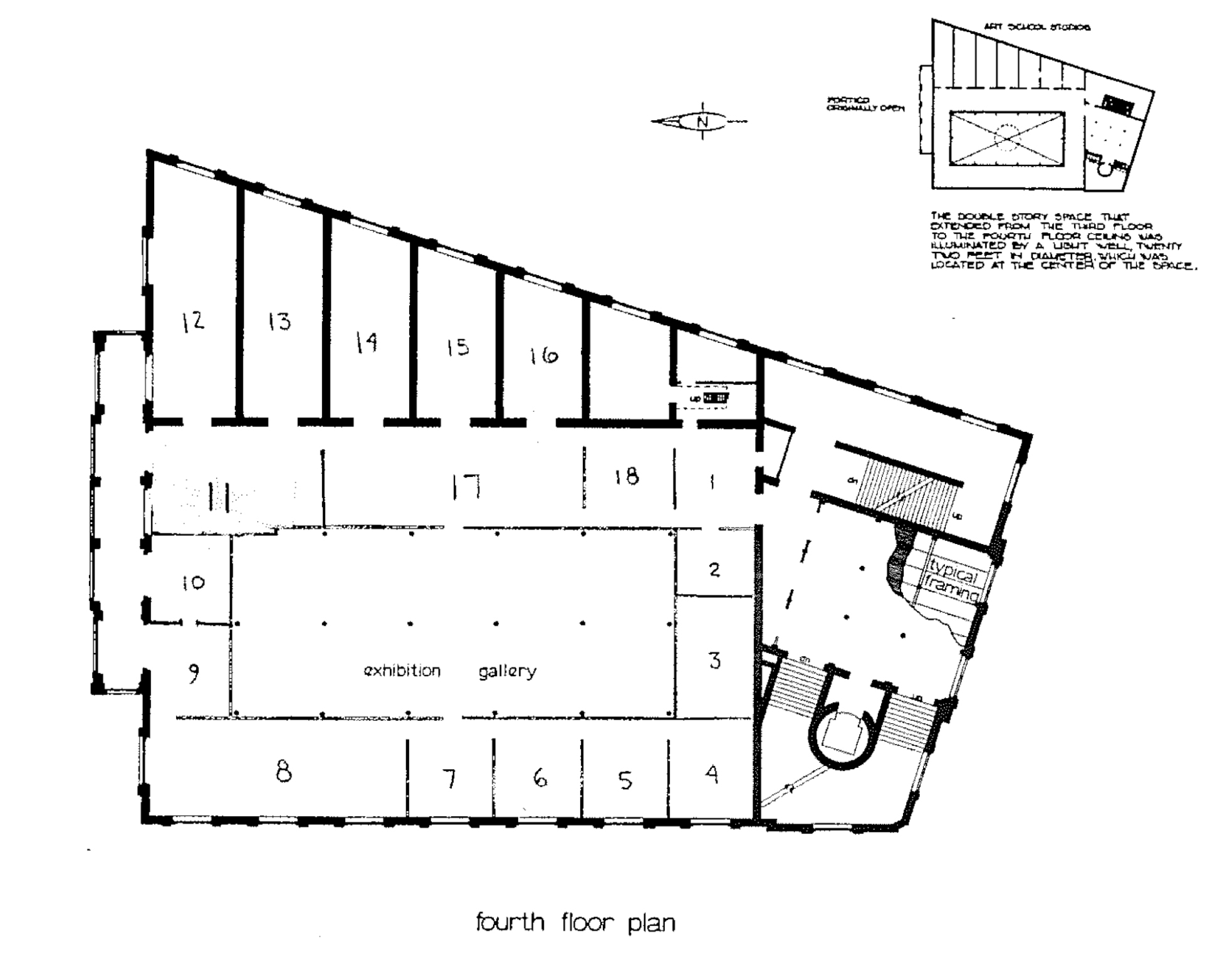

Floor plan, Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration.

After climbing the main staircase of the Cooper Union (or, if we’re feeling daring, we can take an elevator, which, as technology, is starting to become more commonplace) we arrive at the fourth floor, home of the Museum for the Arts of Decoration founded by Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt in 1897. Upon entering, the galleries may first appear a bit overwhelming, with chairs, statues, pillars, carvings, and paintings covering the walls and floor. While some objects have tags attached explaining what they are, many are unlabeled. Visitors instead rely on a collection of scrapbooks, kept in many of the museum galleries, that were created primarily by Eleanor Hewitt. These scrapbooks outline a history of design styles through centuries, geographies, and object types.

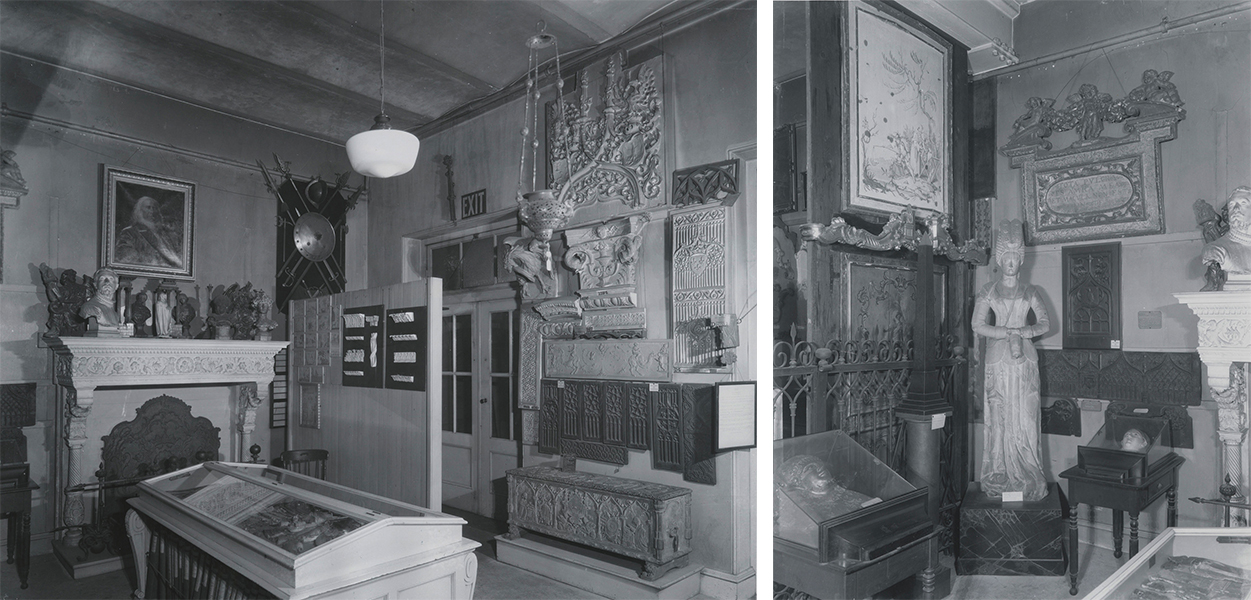

Installation at Cooper Union, 1939. (Gallery 1 on floor plan.)

The first room features gothic and renaissance objects, although mixed into the display are neo-gothic as well as renaissance-inspired works, which show how the styles have been copied and revived through the centuries. In front of a marble mantelpiece crowded with European busts and figurines stands a case lined with Egyptian artifacts. Behind this is a statue of a woman in medieval garb, who stands between a head-shaped Christian reliquary on one side and what may be the head of a sarcophagus on the other. Though scattered across time and place and crowded into the gallery space, various pieces begin to appear in dialogue with one another—the distant gazes of bust, reliquary, and pharaoh seem to share a secret perspective that is inherent to memorial objects.

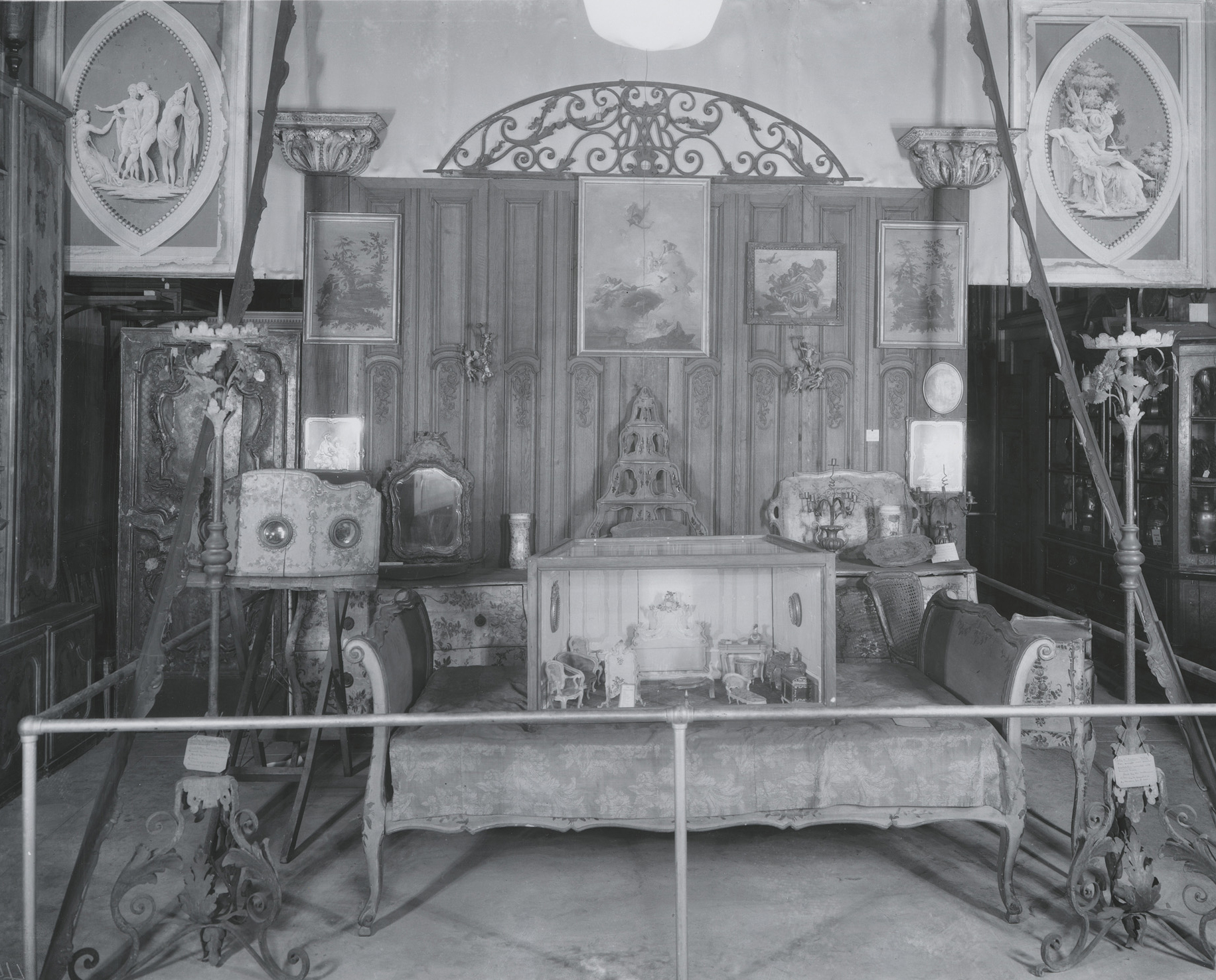

Installation at Cooper Union, 1939. (Gallery 18 on floor plan.)

Passing into the next room we find furniture upon furniture—literally: a miniature salon set is displayed upon a life-sized daybed. Towering candelabra flank the bed and crown molding has been draped diagonally from the ceiling to the floor at the edges of the display. Though it includes many elements of an eighteenth-century Italian salon, the arrangement does not evoke a period room setting. Rather, the objects have been assembled to emphasize the predominant characteristics of the style—floral patterns, gilded details, the blend of straight and curing lines—that are unanimous throughout.

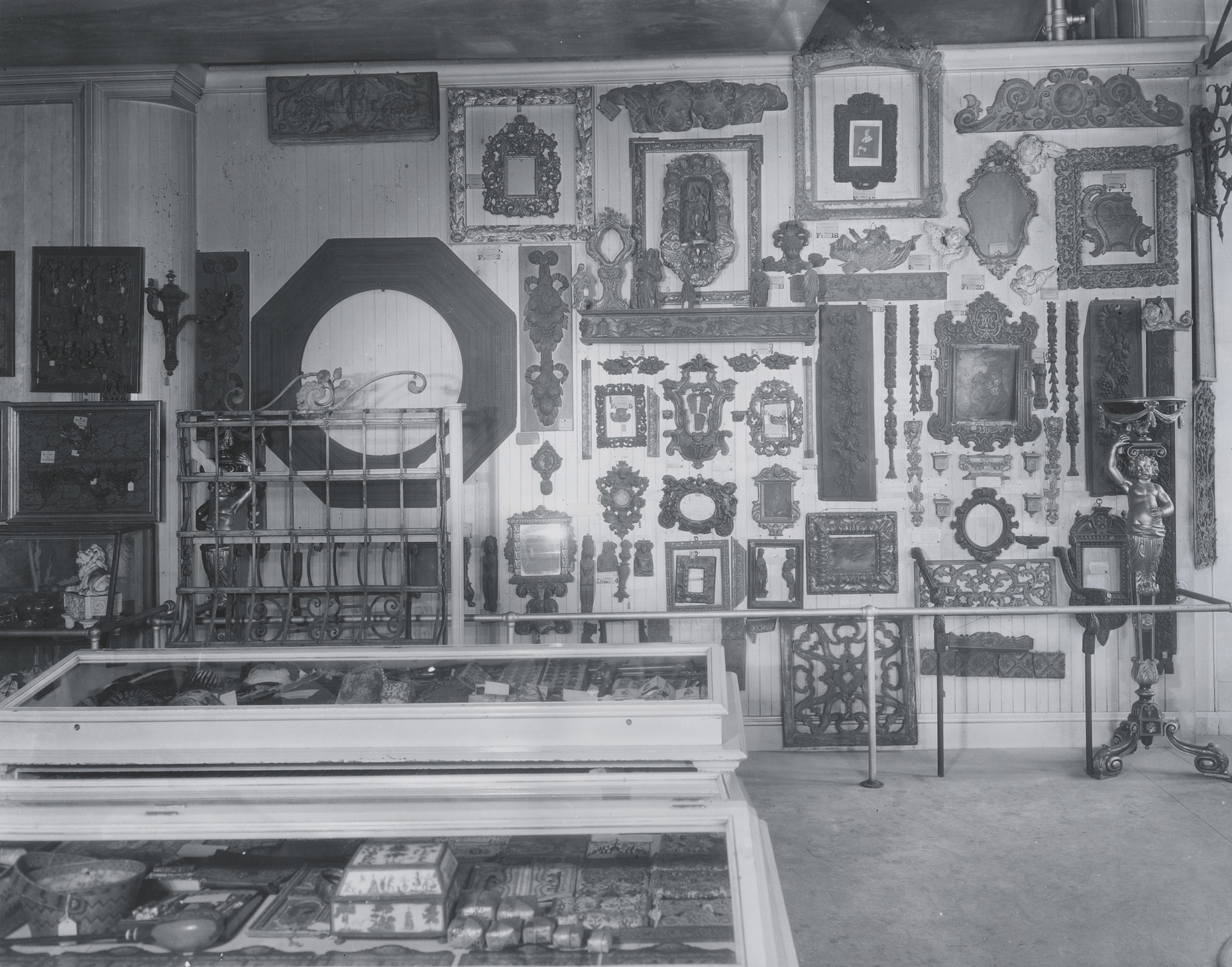

Hallway installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 11 on floor plan.)

Hallway installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 17 on floor plan.)

Hallway installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 17 on floor plan.)

Hallway installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 17 on floor plan.)

As we pass down a hallway lined with eighteenth-century woodcarving (as well as a smattering of metalwork and two sets of samurai armor) four rooms extend out to our right. A row of chairs flanks each side of the rooms and the walls are covered with paintings and engravings of interiors, architecture, decorative motifs, and a surprising amount of cherubs. Notable collections from notable collectors, such as the birdcages of Alexander Drake and the extensive drawings and prints collection of Léon Decloux, also fill the galleries.

Installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 14 on floor plan.)

Installation at Cooper Union Museum, featuring the birdcage collection of Alexander Drake and the drawings and prints collection of Léon Decloux. (Gallery 17 on floor plan.)

At the end of each room, and elsewhere throughout the museum, worktables have been installed so that students and scholars of the decorative arts have a place to sketch or inspect. Benches and stools are also present in many of the galleries, allowing visitors to sit down and spend more time observing the abundant exhibits in detail. These elements signify the importance of the museum as a space for learning, and the way in which study spaces are built into the galleries speaks to the practical purpose of a museum of decorative arts: to inspire and inform. Without access to European interiors and collections (and long before the advent of Google images), the best way for twentieth-century American designers and decorators to learn the history and traditions of their craft was by visiting a museum like the one at Cooper Union.

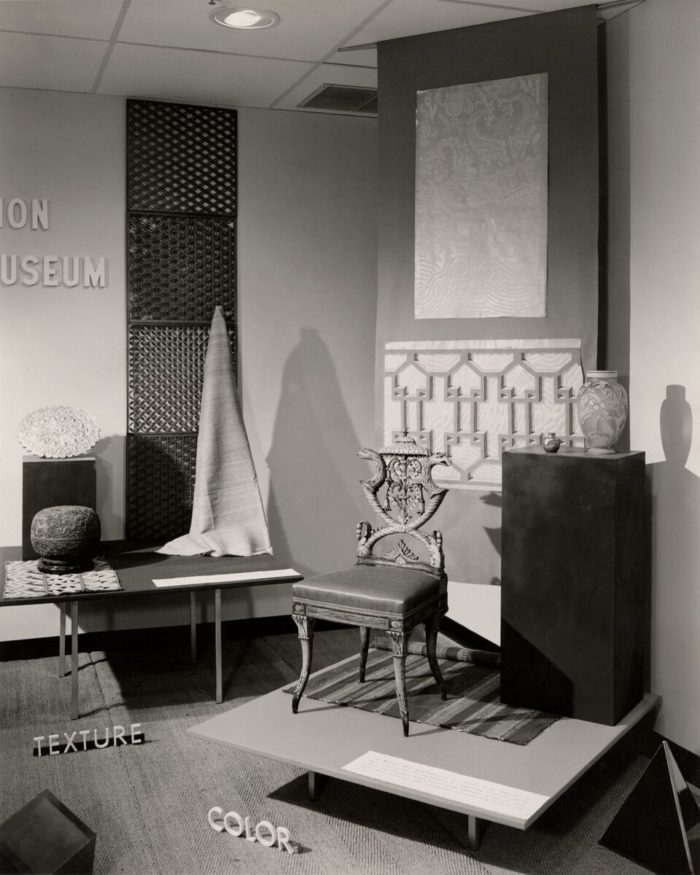

Shortly after this time, a new teaching perspective was ushered into the galleries by Calvin Hathaway, the Cooper Union Museum’s first professional art historian who brought a methodical approach to the collection and its display. Hathaway organized the first themed exhibitions at the museum, demonstrating a shift in curatorial practice from encyclopedic collection presentations to focused curatorial arguments on design.

Design Installation, Cooper Union Museum, 1958.

Past & Present

Education is still a central mission at Cooper Hewitt, but the topics being taught today have shifted, along with the style of displays. As resources for design training and inspiration have become more abundant—from BFA programs to Pinterest to Cooper Hewitt’s digitized collection—design museums appeal to the greater public, in addition to students and scholars. Instead of densely mounting objects into an immersive floor-to-ceiling display, curators may select specific items to support a thesis related to a theme, time period, or type. For example, compare the display of the Rialto Bridge birdcage in 1939 to its 2014 presentation at Cooper Hewitt as part of the exhibition Hewitt Sisters Collect. In the first, the birdcage is positioned as a sample of nineteenth-century style. In the second, it becomes part of a more focused narrative around how and why decorative arts have been collected, specifically by the Hewitt sisters.

Rialto Birdcage installed at Cooper Union Museum in 1939 (gallery 12 on floor plan) and in the exhibition Hewitt Sisters Collect, on display at Cooper Hewitt December 2014–October 2017.

Rialto Bridge Birdcage (Italy), late 19th–early 20th century; Painted wood, bent metal wire, metal; H x W x D: 47.6 x 85.7 x 35.6 cm (18 3/4 x 33 3/4 x 14 in.); Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt; 1916-19-14

With a new interest in telling stories beyond a history of styles and instead looking at technical processes and social factors, displays now featured more focused object selections rather than expansive collections, such as with these many examples of eighteenth-century clocks and hundreds pieces of woodcarvings.

Installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 10 on floor plan.)

Installation at Cooper Union Museum, 1939. (Gallery 11 on floor plan.)

When specific styles are being presented, such as in the exhibition Josef and Anni Albers: Designs for Living (on display at Cooper Hewitt October 1, 2004–February 27, 2005), collections can be displayed in a much sparser manner in order to emphasize the individual objects rather than an overall environment. This allows for a more detailed discussion of each piece, in contrast to the more general identification used in 1939.

Josef and Anni Albers: Designs for Living, on display at Cooper Hewitt October 1, 2004–February 27, 2005.

If an immersive environment is the curatorial objective, as was the case for Thom Browne’s selection of mirrors and reflective objects on display at Cooper Hewitt in 2016, there is a greater tendency today to blend time periods and styles in order to create new connections. Similarly, as we saw in the first room of the museum at Cooper Union, where gothic and Egyptian artifacts shared an interesting relationship, our understanding of an object is informed by the objects around it. By deliberately establishing these connections, curators can emphasize and draw connections between certain elements of design.

Thom Browne Selects, installed at Cooper Hewitt March 4–October 23, 2016.

Objects are always open for interpretation, and while one viewer studies the tiny swirls of metal on the Rialto Bridge birdcage, another may wonder why it’s shaped like a bridge and how it came from Italy to New York (for the answer to that, read about the passionate collector Alexander Drake). Visitor experiences may be informed by how the object is displayed, but ultimately individuals decide interpretation.

Explore 71 gallery views and the vast array of collection objects (some that have since been deaccessioned) on display at the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration in 1939.