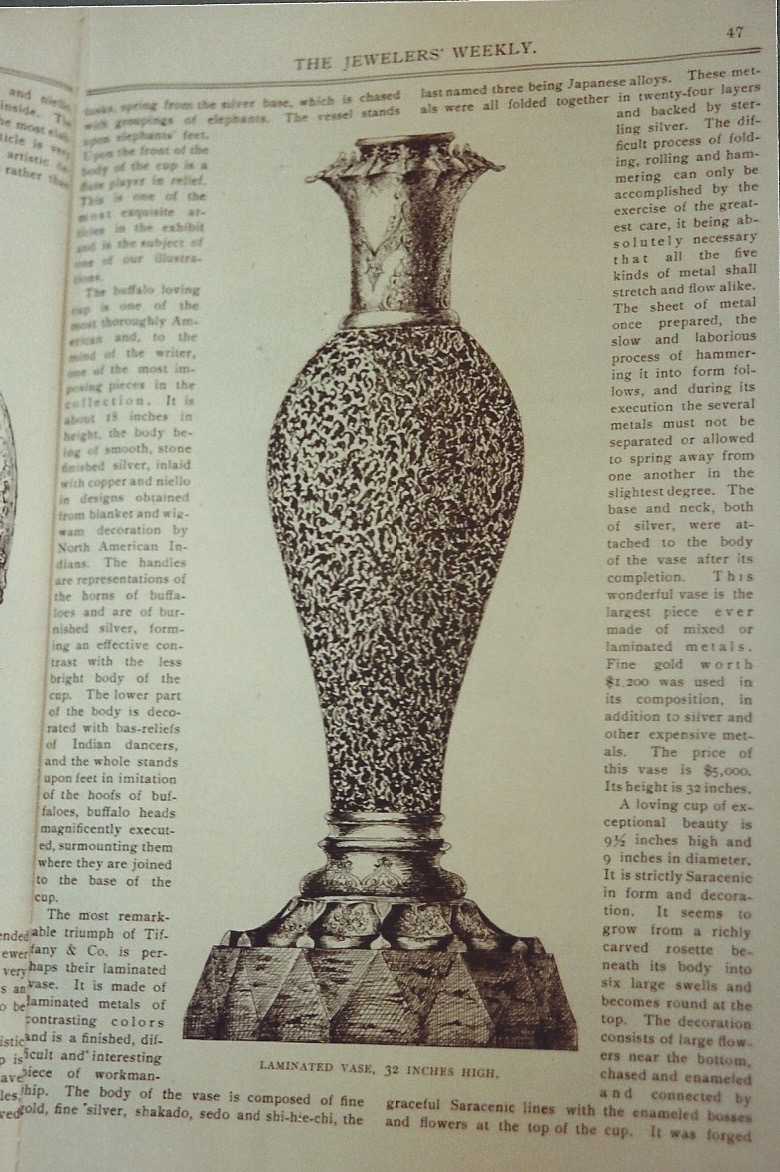

Tiffany & Co. exhibited an extraordinary mixed metal vase at the Paris 1889 Universal Exposition. Created from a layered block of 24-karat gold, silver, and copper, it was 32 inches high, priced at $5000, and the largest known object ever made using the Japanese technique of mokumé. “The most remarkable triumph of Tiffany & Co. is perhaps their laminated vase,” wrote a journalist in The Jewelers’ Weekly. The press was fascinated with how it was made and wrote about the process in great detail. Now altered from a vase mounted on a block of golden ebony to a lamp base with a hole in the bottom, it remains a tour de force in metalwork.

Illustration from The Jewelers’ Weekly (New York: June 6, 1889). Tiffany Archive, Parsippany, NJ.

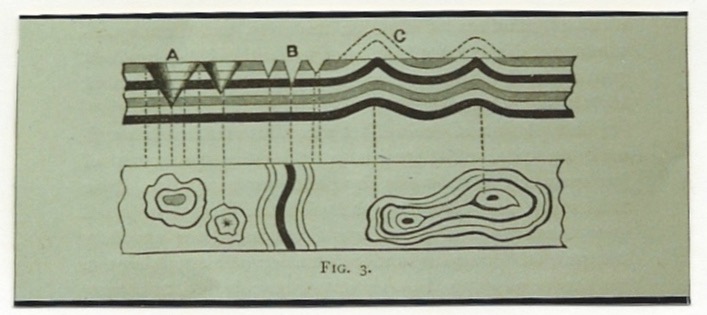

Mokumé, which means “wood grain,” is the term used for a Japanese metalwork technique which combines and manipulates a metal laminate of different colored metals (gold, silver, copper, and other alloys) to create the appearance of wood grain. The pattern results from punching through the metal layers and then compressing them into a single plane. The Tiffany vase was lined with a sheet of silver before being formed into a seamless vase. After the forming, an oxidizing process called “pickling” was used to bring out the colors of the different metals. Finally, the vase was banded in chased and engraved silver.

Diagram of mokumé technique of laminating and working mixed metals to produce a wood grain effect. W.Chandler Roberts-Austen, The Colours of Metals and Alloys (London: Richard Clay & Sons, 1887). E. C. Moore Library, Tiffany Archive, Parsippany, NJ.

Tiffany’s artistic director Edward C. Moore (1827–1891) introduced decorative silver objects inlayed with areas of mixed colored metals as early as 1878 and is credited for the bold use of mokumé in the 1889 Tiffany exhibit. An avid collector of Far and Near Eastern metalwork, Moore amassed over 900 reference books concerned primarily with metallurgy and design for use by Tiffany artisans.

Charles L. Tiffany, master merchant and tastemaker, was impressed by the craze for the Japanese aesthetic and hired British designer and lecturer Christopher Dresser in 1877 to import Japanese goods to sell at Tiffany & Co. Dresser traveled to Japan to study the techniques of Japanese metalwork, ceramic glazes, and other objects. While in Japan, he purchased over nine thousand objects for Tiffany & Co.

Catalog cover from Dresser Collection of Japanese Curios and Articles Selected for Tiffany & Co., 1877. Tiffany Archive, Parsippany, NJ.

Rumors that Dresser also brought back Japanese artisans to work in the Tiffany workrooms were strongly denied by Tiffany in its 1889 Blue Book, which proudly stated that Tiffany’s designers and workmen were all Americans trained by the house of Tiffany.

This vase was the subject of my 1991 thesis for the Cooper Hewitt/Parsons master’s program in the History of Decorative Arts and Design. At that time, I had a wonderful experience researching Japanesque silver design at the Tiffany Archive located in Parsippany, New Jersey. A silversmith working in the Tiffany workshop in New Jersey told me that he learned the technique of mokumé as an apprentice. He elaborated on the tremendous effort of forming the seamless vase, which had to be formed by hand, using wooden forms. The fragile process of raising was complicated by its size. According to the silversmith, it could have taken at least two silversmiths over three hundred hours to hammer the vase into its final shape. The silversmith concluded admiringly: “It was quite a feat to get something like that up that clean and precise” (interview with silversmith and Coordinator of Hollowware, Parsippany, New Jersey, February 1991).

The vase is currently on display in gallery 213 as part of “Passion for the Exotic: Japonism.”

Source:

Masinter, Margery. Tiffany’s Mastery of Mokumé: Paris, 1889. Cooper-Hewitt Library, NK 7198 T5M39, 1991a

Electronic version available at siris-libraries.si.edu.

Margery Masinter serves on the Board of Trustees, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She co-authors the “Meet the Hewitts” blog, a monthly feature about the founders and early days of the museum published in the Cooper Hewitt Design News.