Fig. 1: Brompton Folding Bicycle, 2016; Designed by Andrew Ritchie (British, b. 1947); Manufactured by Brompton Bicycle (Brentford, England); Assembled bent, brazed, and lacquered tubular steel (frame) and titanium (mudguards), synthetic (saddle), molded rubber and Kevlar (tires); H x W x L (open): 57.2 x 55.2 x 147.3 cm (22 1/2 x 21 3/4 x 58 in.); Gift of Brompton Bicycle, 2016-19-1

Persistent advancements in materials and technologies, based increasingly on science as well as on the imagination of individuals, has produced a large body of work defined as contemporary design. Much of it has to do with the way things are made, often using new processes. We have mastered assembly-line mass production as exemplified by such ubiquitous products as the white plastic chair available all over the world for only a few dollars, and microchips—the “brains” of our digital products—fabricated for pennies. Even low-cost cars are now technically excellent. With the definition of design extending far beyond chairs and cups and saucers to new notions of mobility and entire systems, four trends and challenges characterize our era: digital technologies, customization, environmental concerns, and well-being.

Fig. 2: Smart Balaclava prototype, 2016; Designed by Nottingham Trent University (Nottingham, England) and Stoll GmBH (Germany); 3D-knitted with conductive yarn, electric heating elements, NFC chips, photovoltaic cells. Electric-conductive yarn powered by a small rechargeable cell battery gently warms the air inhaled by the wearer.

We have created an information-driven society where digital technologies have radically transformed the way we communicate, manufacture, live, and work. They have improved our daily lives, made many things easier—often more enjoyable—and they have changed how we design. We expect our products to do so much more for us. In fact, they have become so complex we no longer think in terms of isolated objects, but of systems, like mesh networking or autonomous vehicles that together with other modes of transportation, such as portable folding bicycles (fig. 1, above), are transforming mobility and our urban infrastructure. Designers, engineers, scientists, manufacturers, and the general public are sharing their expertise, their data, their findings, yielding multidisciplinary approaches to research and design. Not only are things being made in new ways, but this interdependence of various expertise is leading to new expressions of materials and forms specific to our time, resulting in smarter, more responsive, more adaptable, and higher performing products and experiences. Smart textiles, for instance, with integrated technology can track personal usage and regulate temperatures (fig. 2).

Personalizing objects for self-expression, improvement, or for fun has been done for centuries, but recent strides in digital manufacturing technologies are also enabling us to customize products. A benefit of such customization is experimentation—varying a design merely with a change in software rather than the complete retooling of a production line (fig. 3, 4). We can custom order a pair of Nike shoes from a “kit of parts” similar to when designers Charles and Ray Eames ordered standardized steel parts to construct their 1949 Case Study House; however, once the materials were delivered, the Eameses changed their minds and assembled something different than originally planned. Undeniably, the most transformative object of our time is the smartphone, which addresses both customization and doing more with less. We personalize them by downloading apps that cater to our preferences, and the options continue to increase daily. A beneficial byproduct of incorporating so many previously separate products into one is that we provide more opportunities to create and to perform numerous tasks with a single device.

Fig. 3 (left): Vessels, from the GLASS series, 2015; Designed by Neri Oxman (Israeli-American, b. 1976) and the Mediated Matter Group, MIT Media Lab (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA); 3D-printed glass; Museum purchase from General Acquisitions Endowment Fund and through gift of MIT Media Lab, 2016-54-1-a,b/9-a,b. Fig 4 (right): Kinematics Dress #4, 2015; Designed by Nervous System (Somerville, Massachusetts, USA), printed by Shapeways (New York, New York, USA); Nylon, 3D printed by selective laser sintering; Museum purchase from General Acquisitions Endowment Fund, 2015-18-1.

A significant change in recent years is marked by the increased engagement of the user throughout the design process, particularly those with special needs or an extreme condition. Consequently, we’re becoming much better at understanding people and behaviors, defining and designing products that are adapted to individual users. In fact, although the greatest beneficiaries of product customization are people with special needs, designing for extreme conditions oftentimes is more inclusive, such as curb cuts in sidewalks benefiting a multitude of users. Unlike one-size-fits-all manufacturing processes, 3D printing gives us more opportunities to improve comfort and adapt products to an individual’s body, shape, and size, including high-performance prosthetics such as wheelchairs or the UNYQ Align Scoliosis brace (fig. 5).

Fig. 5 (left): UNYQ Align Scoliosis Brace Prototype, 2017; Designed by Francis Bitonti (American, b. 1983) and Studio Bitonti; Manufactured by UNYQ (San Francisco, California, USA); 3D-printed nylon; H xWxD:43.5×28×27.5cm(171/8in.×11in. × 10 13/16 in.); Museum purchase from General Acquisitions Endowment Fund, 2017-12-1. Fig. 6 (right): Alfi High Back Chair, 2015; Designed by Jasper Morrison (British, b. 1959); Manufactured by Emeco (Hanover, Pennsylvania, USA); Milled polypropylene and wood fiber, hand-carved ash; H x WxD:80×43.2×50.2cm(311/2in.×17in.×19 3/4 in.); Gift of Emeco, 2015-25-1

Thanks to science and digital technologies, we are adding metrics and efficiencies to design, optimizing performance, improving structural capabilities of buildings and products, and reducing material waste. Environmental and sustainability issues have become the conscience and creative challenge of many designers and manufacturers. For example, Jasper Morrison’s Alfi chair for Emeco, made of reclaimed wood fibers and polypropylene and responsibly harvested ash wood (fig. 6), or Benjamin Hubert’s modular acoustic panel system made of pressed recycled PET (fig. 7).

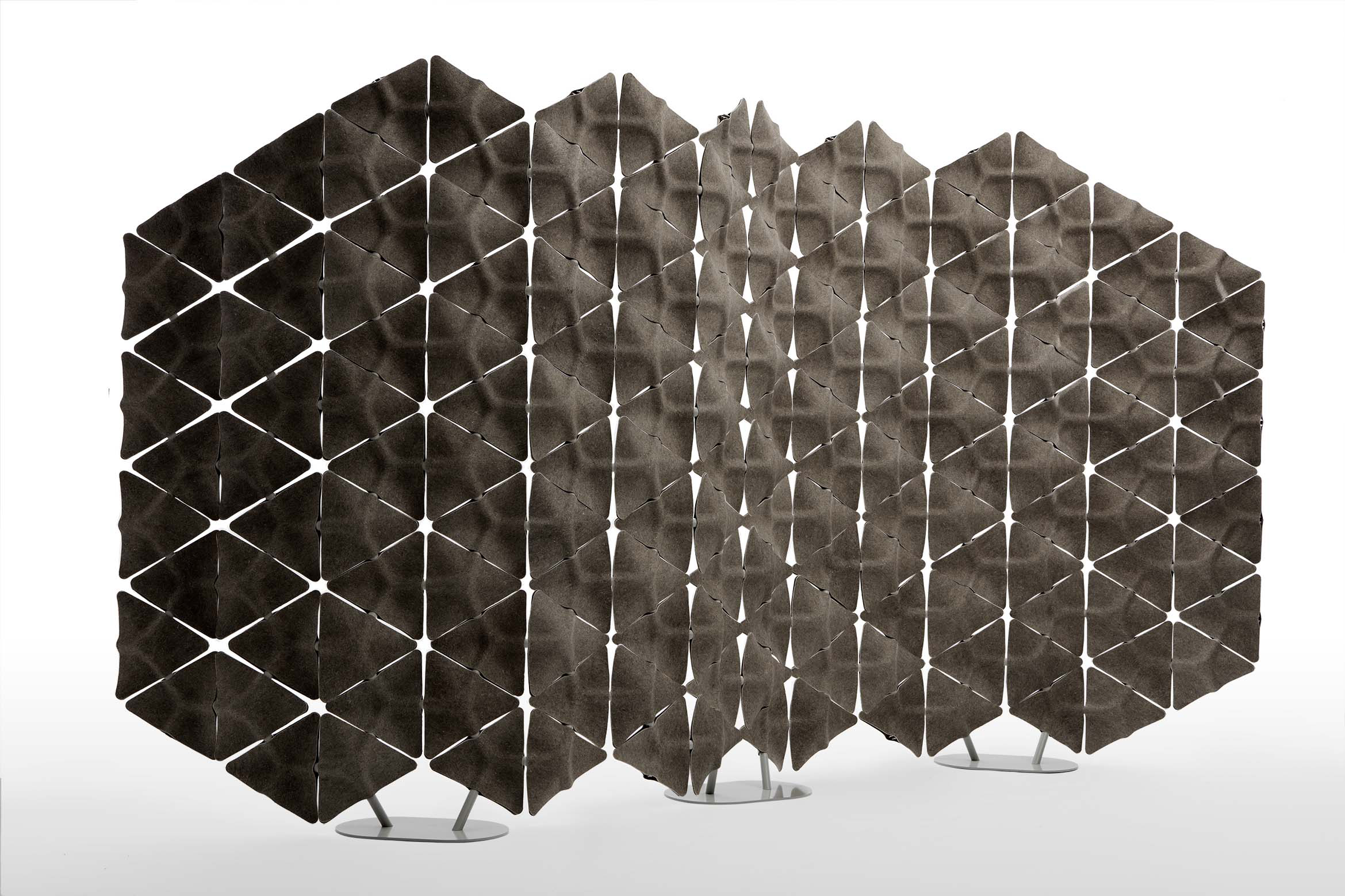

Fig. 7: Scale Acoustic Panel System, 2016; Designed by Benjamin Hubert (British, b. 1984), Layer Design: Manufactured by Woven Image (Brookvale NSW, Australia); Pressed recycled PET (textile), injection- molded ABS plastic, recycled aluminum, magnets

There is hope that the enlarged territory encompassed by design will include the many environments of neglect and poverty in our contemporary cities. We may find opportunities in the moral and economic pressure toward greater social equity in our economically advanced cities through design, which are able to tackle situations that demand success in both physical and social dimensions. This expansion of design to play a role in the world’s poorest and largest urban centers requires a greater sense of scale and numbers. Already some of the world’s most deprived urban inhabitants have organized into networks of self-help communities, collaborating with professional designers and harnessing their energy and skills to advance themselves.

Designers are optimists. They are driven to make things better, to question, to innovate, to synthesize and create meaningful experiences that ultimately improve and enhance our quality of life. Often, they see possibilities where others don’t, and as a creative force they have enormous impact. In recent years, the public, too, has become much more design savvy, self-reliant, and adaptable, demanding better-performing, smarter products that do more with less. This is a period of constant, dramatic, and dynamic change. As the digital, virtual, and material worlds increasingly co-mingle, unexpected designs and solutions will arise and designers will continue to push the boundaries of possibilities, imagination, and resourcefulness in their efforts to make a difference.

Cara McCarty is the Curatorial Director at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2017 issue of Design Journal.