Written by Steven Landau

As a company of designers and producers of tactile maps and models, Touch Graphics, Inc. usually focuses on products that communicate spatial information through the sense of touch for use by visually impaired students and museum visitors. Occasionally, the company develops tools to support blind artists and scientists. One of our recent explorations involves a collaborative project with a practicing sculptor, Emilie Gossiaux, who explores new modes of self-expression through touch. The result of this experimentation is a large rubber drawing board, a simple device that provides real-time tactile feedback as you draw.

The role of vision in figure drawing is easy to demonstrate: if you close your eyes or put on a blindfold and then try to draw a picture of your dog, for example, the results will probably be unrecognizable. Drawing a good likeness requires visual feedback: you have to see the line as it is being drawn, so that you can continually correct your movements to achieve the desired result. Without vision we have no way to perceive lines as we make them, and no way to experience the picture as a whole.

Emilie Gossiaux holds up her sketch of her guide dog, London, as London pokes her nose up into the photo, bottom right. Emilie used the Blackboard tactile drawing board from Sensational Books (www.sensationalbooks.com).

A Tactile Drawing Board

A person can learn to draw without seeing, by replacing visual perceptions with tactile feedback. In pioneering experiments in the 1970s, psychologist John Kennedy at the University of Toronto taught adults who had never had sight before how to draw using a rubber mat placed under a sheet of drawing paper. Their pencils created raised furrows in the paper as they pressed down into the resilient surface, and the artists could feel these furrows with one hand as they drew with the other hand. When they weren’t drawing, they were using both hands to scan the emerging tactile composition, so they could comprehend and plan the overall picture, placing each new mark in the right location to create simple, recognizable figures.

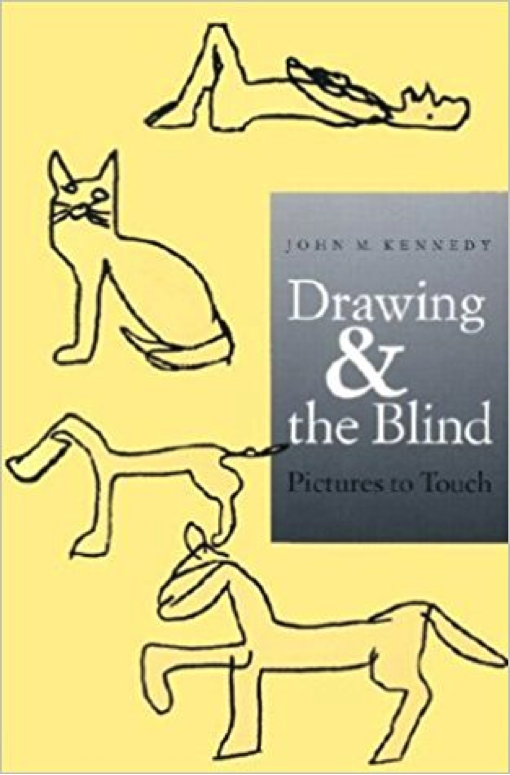

John Kennedy’s Drawing & the Blind book cover showing simple side views of a person lying down, a cat, a dog, and a horse. These sketches were made by a blind student using the rubber-mat method of tactile drawing.

A Power User

Sculptor Emilie Gossiaux, who has no light perception after a bike accident seven years ago, uses a tactile drawing board like the one in the earlier study to sketch and illustrate ideas about her artworks. After years of practice, the experience feels to her like visual drawing, which is not surprising, since fMRI studies at Harvard in the 1990’s showed the same parts of the brain lighting up during both activities. Gossiaux’s pictorial explorations using this simple tool are pushing the boundaries of tactile portraiture, showing us a new level of expressiveness and mastery of this form of sensory substitution.

Still image from a video of Emilie Gossiaux demonstrating the tactile drawing board in her studio. She holds the pencil in one hand and feels the lines she is making with the other hand.

Design of Tools

To achieve these results, Gossiaux experiments with different surfaces, stylii and paper, to optimize the tactile drawing experience and find the “sweet spot,” in which she receives the most accurate tactile information, capturing not only the placement of lines, but also visual characteristics like darkness or thickness. Pressing a little harder with the stylus should result in a barely perceptibly higher raised line; this requires a rubber pad with just the right resiliency, and paper that stretches a bit but does not rip when you really bear down. A good analogy is a singer who listens to herself through the highest-quality headphones during recording sessions: the more precisely she can hear herself, the more accurate and steady her pitch and timbre.

Tactile Mindfulness

While Gossiaux’s work reveals exceptional artistry and skill, probably anyone with good fingertip sensitivity can learn to use the tactile drawing board to make simple figures. The key to developing these abilities is temporary or permanent lack of vision. Just putting on a blindfold causes us to switch our focus from vision to touch, bringing tactile sensations to the perceptual foreground. Because vision is effortless, operates at a distance, and can take in an entire scene at once, it always supplants touch as the dominant sense. Sighted people can learn tactile mindfulness with training but as soon as their blindfold is removed, vision takes over and their newly-acquired tactile skill will probably start to fade.

Mastery

But for those living without vision for many years, tactile ability can become highly refined through constant use and the absence of visual distractions. The tactile drawing board is a low cost, low tech, portable tool for non-visual self-expression and communication, that builds tactile mindfulness through its continued use, leading to some extraordinary artistic accomplishments, and highly developed manual skills that probably carry over into every aspect of the artist’s life. As with any skill, the key to achieving mastery appears to be intensive practice and access to appropriate tools, adapted to one’s specific needs and preferences.

Steven Landau is the president of Touch Graphics, a company he founded in 1998 that aims to refine and commercialize methods for tactile graphics production. This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Design Journal.