Written by Ellen Lupton and Andrea Lipps

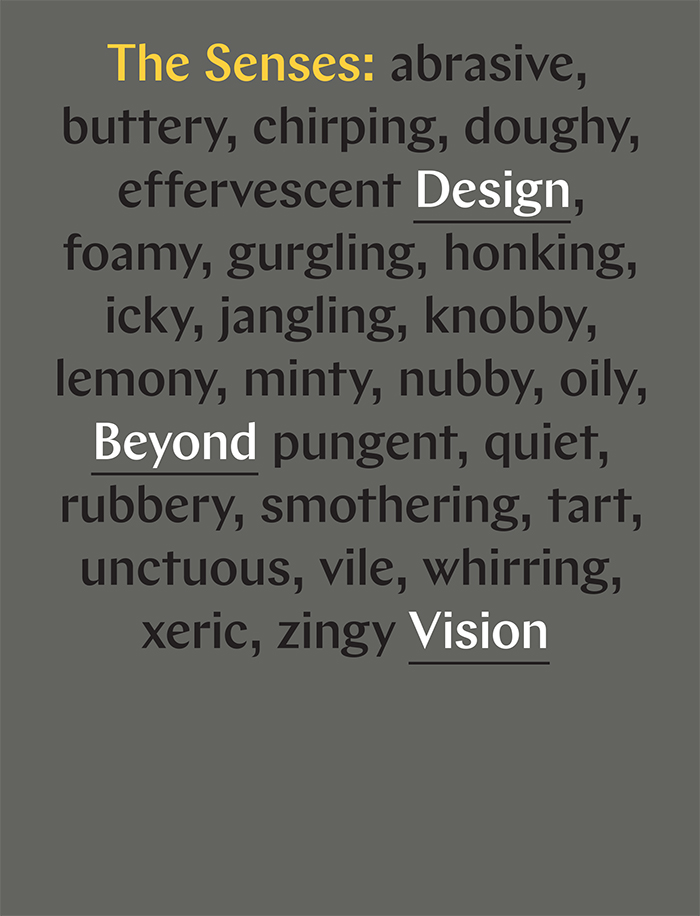

Excerpted from The Senses: Design Beyond Vision , by Ellen Lupton and Andrea Lipps (New York: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and Princeton Architectural Press, 2018).

Reaching beyond vision, this project is a manifesto for an inclusive, multisensory design practice. Sensory design activates touch, sound, smell, taste, and the wisdom of the body. Sensory design supports everyone’s opportunity to receive information, explore the world, and experience joy, wonder, and social connections, regardless of our sensory abilities. This book documents extraordinary work by some of the world’s most creative thinkers, and it gathers together ideas and principles for extending the sensory richness of products, environments, and media.

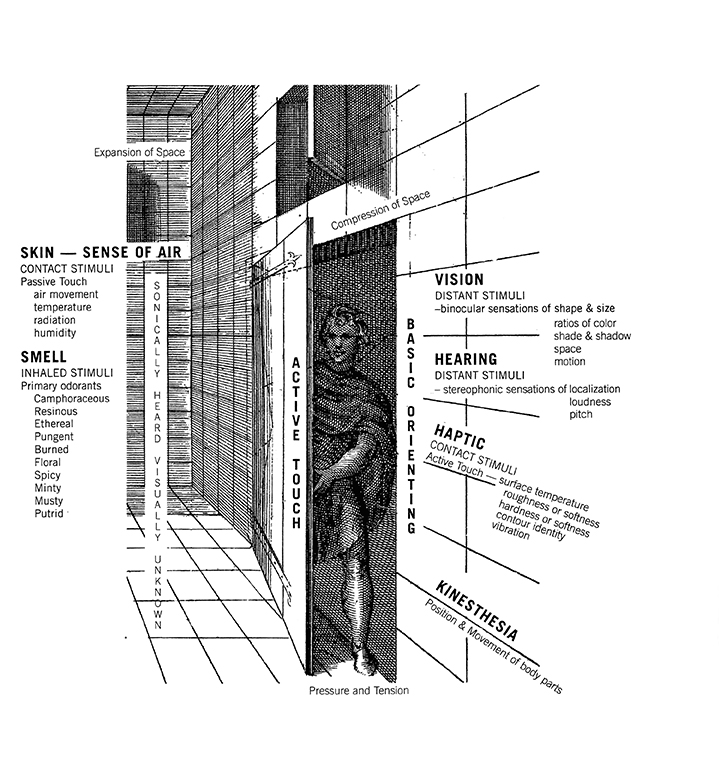

Joy Monice Malnar and Frank Vodvarka, Ranges of the Senses, from Sensory Design, University of Minnesota Press; © 2004 by Joy Monice Malnar and Frank Vodvarka

This essay accompanies the book and exhibition The Senses: Design Beyond Vision. As curators at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, we sought out work and insights from designers, researchers, and users. We searched for artifacts that could be directly experienced by the museum’s visitors. We learned about the fusion of mind, body, and sensation.

The senses mix with memory. From infancy, human creatures engage in countless acts of lifting, licking, touching, sniffing, throwing, dropping, hearing, balancing, and more, constantly testing the edges of physics to understand (or “make sense of”) the world we were born to discover. The brain fires neurons, prunes synapses, and forges pathways. Thus meaning and memory take form. When we encounter an oddly shaped coffee cup or an updated operating system, we don’t see it as completely alien but focus our attention on disparities between what’s new and what we’ve encountered in the past. What would this page taste like if you licked it? What sound would this book make if you dropped it? We can imagine these sensations without needing to enact them. Prior experience tells our brains what to expect.

The senses move us through space. The eye or ear is not a fixed camera or a microphone wired to a wall; our sense organs are connected to a head that turns, arms that reach, and bodies that wander and seek.[1] The sounds, smells, and shifting shadows of a room or a streetscape help orient this knowledge-hungry body. Sensory experience hits us from all directions. Traditionally, designers focused on creating static artifacts — the monument, the vessel, the elegant monogram, or the essential logotype. Today, designers think about how people interact over time with a product or place.

The senses merge and mingle. As kids, we learn to think of the five senses as separate channels, like five radio stations playing at once. Some stations buzz along in the background, while others dominate. The real picture is more complex. As the brain combines different modes of information, the senses mutually change one another. A cold, fizzy soda tastes better than a warm, flat one. A bar of chocolate wrapped in richly patterned paper primes our desire for the bittersweet goodness within. Golden light makes a room feel peaceful and warm, while cool daylight hues charge it with energy. Designers consider interaction of bodies and things. What sound does a chair make when it scrapes along the floor? How hard does a button need to be pressed to register a response? How much does a surface flex when we push against it?

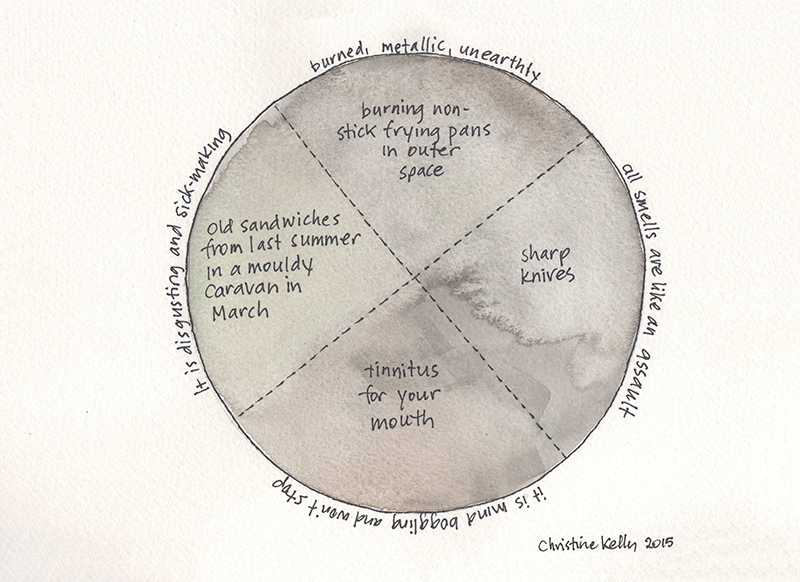

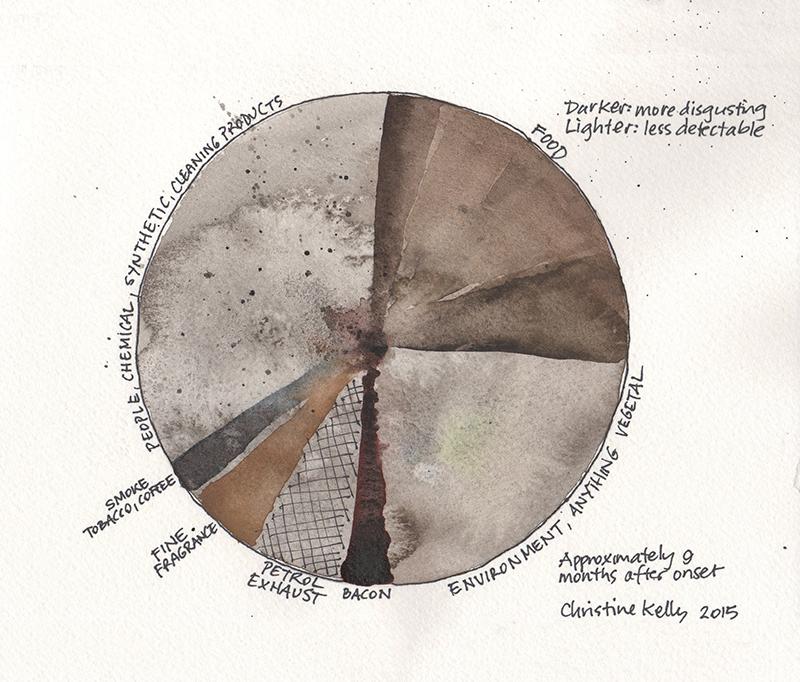

The senses are unique to every person. Some people have smell receptors that make broccoli taste appallingly bitter; to others, cilantro tastes like soap. Some people have a diminished sense of smell. This condition, called anosmia, vastly diminishes the pleasure of eating and of otherwise exploring the world; it affects six million Americans. Christine Kelly, who became anosmic after a sinus infection, creates smell wheels that illustrate how her sense of smell has been distorted—smells that should pique the appetite or calm the nerves became noxious and muddy. People with color blindness see red and green or blue and yellow as similar hues. Individuals with multiple sclerosis, leprosy, neuropathy, or severe burns can lose sensitivity to touch. Individuals with SPD (sensory processing disorder) can feel unbearable distress from tags and seams in clothing or crave constant bodily motion. Some sensory differences yield extreme pleasure. ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) is a delicious tingling in the scalp and spine triggered in some people by sounds such as crunching, crackling, or rubbing. In videos popular with the ASMR community, manicured hands gently crush plastic-wrapped pastries or rustle crisp sheets of paper, narrated by whispering voiceovers.

Anosmia smell wheel showing the monotony of smell loss, 2015; Christine Kelly (American and British, b. 1959); Watercolor and ink; Courtesy of Christine Kelly

Anosmia smell wheel 9 months after onset showing more intense but still not pleasant smell experiences, 2015; Christine Kelly (American and British, b. 1959); Watercolor and ink; Courtesy of Christine Kelly

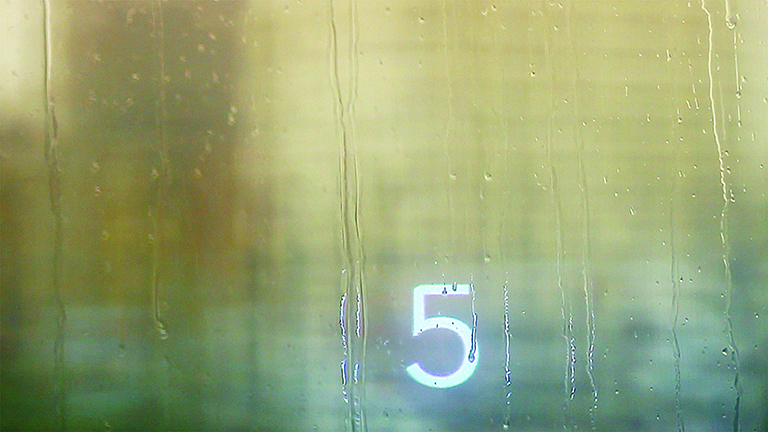

The senses trigger and amplify other senses. For people with synesthesia, the brain makes cross-connections between the senses. Music can play in color, while letters can conjure sounds or textures. Neurologist Richard E. Cytowic has devoted his career to studying synesthesia. Once seen as a rare disorder, synesthesia is now known to be a widespread condition with dozens of variations, affecting one out of every twenty-three individuals. A child with synesthesia begins establishing cross-sensory connections early in life. When learning the alphabet, a child might link the color green with words that start with g. Such associations become fixed for life, cemented both by nurture and nature.[2] David Genco, a graphic designer with synesthesia, assigns color, gender, and personality to numbers. In his interactive video project Synesthetic Calculus, video clips visualize unique ways of remembering numbers via sensory connections.

Synesthetic Calculus (stills), 2012; David Genco (Luxembourgian, b. 1985); Video; Courtesy of David Genco

Synesthetic Calculus (stills), 2012; David Genco (Luxembourgian, b. 1985); Video; Courtesy of David Genco

Synesthetic Calculus (stills), 2012; David Genco (Luxembourgian, b. 1985); Video; Courtesy of David Genco

The senses are plastic. Cytowic compares synesthesia to fireworks — a sudden spray of color is triggered by a word, letter, or sound. While synesthesia is a specific neurological condition, some degree of sensory alchemy permeates daily life. “Inwardly, we are all synesthetes,” Cytowic told us. “We just don’t notice how our senses interact.” The human mind has a gift for connecting sensations — we link tastes and colors, sounds and spaces. Some people who are deaf or blind become acutely attuned to multiple senses, using areas of the brain typically devoted to sight or sound to process other inputs. People perceive objects and spaces with sound and touch as well as with vision. People experience sound by feeling vibrations and seeing movements as well as hearing by ear.

Scientists are creating sensory substitution devices that enable a blind person to convert audio signals into low–resolution mental images, or that allow a deaf person to convert a grid of vibrations felt against the skin into recognizable speech. “Lingual vision” is the ability to understand features of an object via electrical stimulation of the tongue. A lollipop-shaped stimulator placed inside the mouth can help a soldier traverse a dark night, or a diver navigate a murky sea, or a blind person perceive the outlines of objects and their locations in space. Cytowic told us, “The brain doesn’t care where the signals come from — your eyes or your big toe. Send in anything, and the brain will figure it out. Reality takes shape in the dark theater of the brain.”[3]

The senses chatter constantly with one another. Indeed, it takes serious mental effort to pull our sensations apart. It is tough to separate the sweet, sour taste of a mango from its bright, caramel-tinged aroma. Do you sometimes close your eyes when trying to decipher a faint sound or an odd aftertaste? That’s why the lights go down before a concert begins. Darkness helps us hear more clearly. Shutting out visual signals can help bring other senses into focus. In his essay “Designing LIVE,” Bruce Mau tells sighted designers, “To design for all the senses: start with a blindfold.”

The senses have long been dominated by vision. In the Western tradition, the eye symbolizes knowledge and enlightenment. Visual observation is the bedrock of modern science. Today, digital devices pump out an endless feed of graphics and text, stoking demand for quick hits of visual energy — often at the expense of our other senses. Smell sits at the bottom of the pyramid, in part because it resists attempts to be visually diagrammed, as Adam Jasper and Nadia Wagner point out in their essay “Smell.”

Sensory design rebels against the tyranny of the eye. When Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa published his book Eyes of the Skin in 1996, many architects began to question the dominance of visual form and the Western obsession with “ocularcentrism.” The overbearing eye fosters detachment and isolation, breeding the harsh atmosphere of modern schools and hospitals.[4] Architecture, says Pallasmaa, should embrace and envelop the body with authentic materials and tactile forms. Sensory design slows space down, making it feel thick rather than thin. An intimate room reverberates with shifting shadows and surfaces wrought from wood, wool, or stone. An atrium changes with the sun. Rough walls and dense fabrics absorb clatter and din.

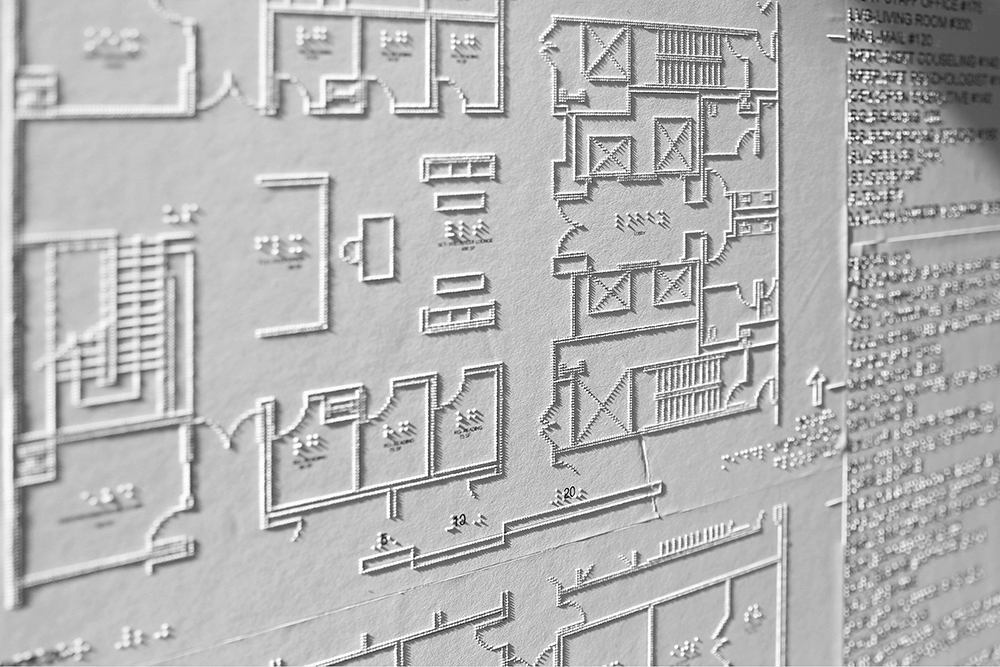

Sensory design enhances health and well-being. A scent player for Alzheimer’s patients stimulates the appetite by releasing the smell of grapefruit, curry, or chocolate cake at mealtimes. Tactile graphics are used to communicate ideas through the sense of touch. Buildings with spacious hallways and vibrant materials accommodate everyone, including people experiencing blindness, deafness, or memory loss.

Tactile Architectural Drawing (detail), San Francisco LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, 2015; Chris Downey (American, b. 1962); Embossed digital print with ink, raised lines, and braille; Photo by Don Fogg

Sensory design is inclusive. Each person’s sensory abilities change over the course of a lifetime. By addressing multiple senses, designers support the diversity of the human condition. In his essay “The Inclusive Museum,” Sina Bahram points out that museums have long used ramps and elevators to ensure that visitors with disabilities can enter the building, but museums often fail to offer these visitors a rich experience once they get inside. Universal design expert Karen Kraskow conducted interviews with singers, an artist, a tech consultant, an architect, a former jewelry designer, and others who are blind or visually impaired, learning how they live and flourish.

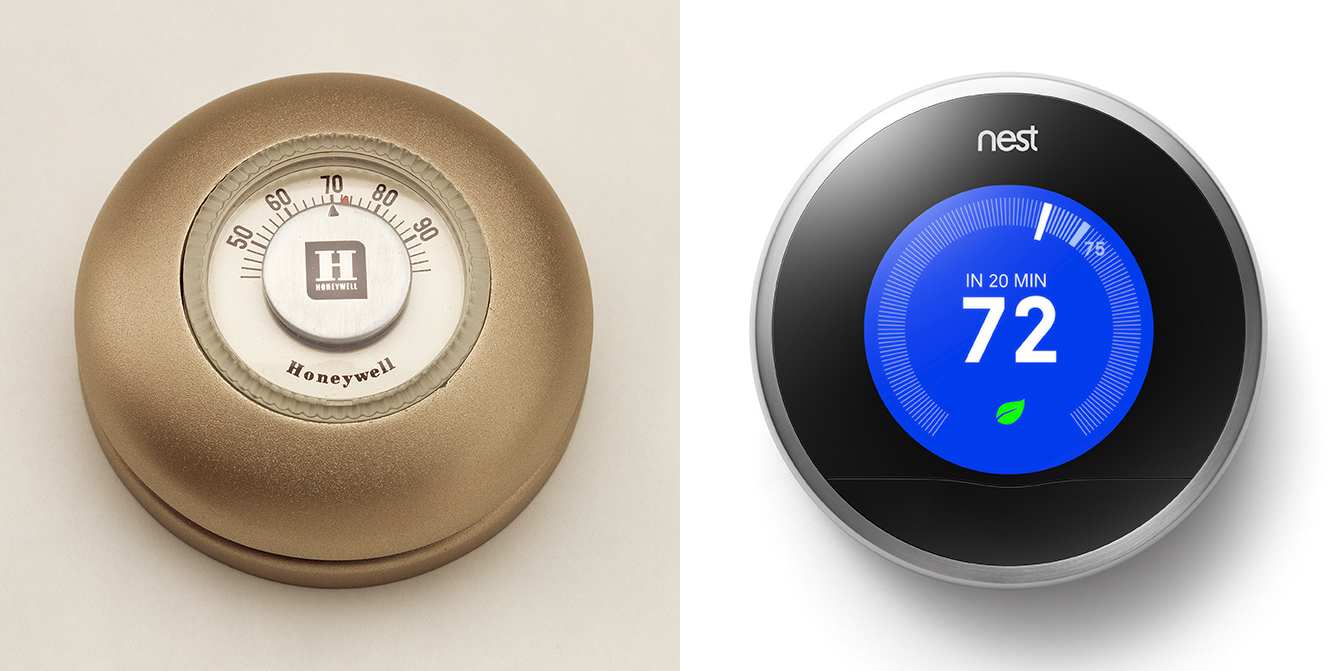

Sensory design embraces human diversity. According to the New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, inclusive design creates a “multisensory enhanced environment that accommodates a wide range of physical and mental abilities for people of all ages.”[5] People sense the movement of objects, air, and bodies through touch, sound, and smell as well as vision. Acoustic designer Shane Myrbeck (Arup) notes that the classic Honeywell thermostat is an accessible design that offers an eyes-free tactile interface, while operating the digital touch screen of the Nest requires vision. Smartphone interfaces promote accessibility for blind and low-vision users by combining audio and haptic signals with touch-screen technology. Apple’s iPhone has a built-in screen reader and an array of accessibility modes — available to every user of every device. Steven Landau and Joshua Miele are creating tactile models, maps, and diagrams, while Liron Gino has designed a music player that translates sound into tangible vibrations.

(left) T-86 Round Thermostat, 1953; Henry Dreyfuss (American, 1904–1972); Manufactured by Honeywell, Inc. (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, founded 1906); Metal, molded plastic; 4.5 × 8 cm diam. (1 3/4 × 3 1/8 in.); Gift of Honeywell Inc., 1994-37-1; Photo by Hiro Ihara © Smithsonian Institution. (right) Nest Learning Thermostat, 2012; Tony Fadell (American, b. 1969); Manufactured by Nest Labs, Inc.; Forged stainless steel, glass, injection-molded plastic, electronic components; 4.1 x 8.1 cm diam. (1 5/8 × 3 3/16 in.); Gift of Nest Labs, Inc., 2013-19-2-a,b; Photo by Ellen McDermott © Smithsonian Institution

Sensory design considers not just the shape of things but how things shape us—our behavior, our emotions, our truth. Sensations respond to an insistent, ever-changing environment. When our body presses into the cushioned surface of a chair, both body and chair give and react. We grab objects in order to use them as tools for breaking, bending, mashing, or joining together other objects and materials. Tools are active extensions of our sense of touch. Tasting food is more than a chemical response—it involves the muscular, skeletal action of crushing and transforming matter. We use our senses to change our world.[6]

Sensory design honors the pulse of living, breathing spaces. The loudest car on a train is the “quiet car.” The carriage shakes along the tracks and shudders against the damaged infrastructure. Talking is forbidden, but you can hear the clink of ice, the crackle of food wrappers, and the whir of people slurping, sipping, breathing, and snoring. Libraries, too, are quiet places filled with sound. Karen van Lengen and James Welty explored the sounds of the New York Public Library, the Seagram Building, and other iconic interiors for their 2015 project Soundscape New York. Van Lengen created drawings inspired by sounds in space, from a rolling cart to books opening and closing. Welty created a temporal animation of van Lengen’s drawings.

New York Soundscape: New York Public Library (still), 2015; Karen van Lengen (American, b. 1951) and James Welty (American, b. 1950); Animated film; Collection of the Museum of the City of New York; Courtesy of the designers

Sensory design is grounded in phenomenology. This field of thought explores how humans and other creatures perceive the world. Philosophers in the early 20th century brought new attention to bodily perception. Scientists and philosophers since the Renaissance had separated mind and body, distrusting sensation as mere illusion and favoring instead objective mathematical laws. Phenomenology situates knowledge in the body: sensual encounters enable consciousness.[7] The human organism is an open, breathing membrane in continual contact with its surroundings. The earth moves as we move along it. Dust swirls, leaves crush, and molecules shiver into waves of sound. As other creatures cross our path, we ripple into action to create sounds and gestures.

Sensory design knits together time and space. When we look at a building, our gaze darts from its small details to its larger volumes to create an understanding of the whole. In their landmark book Sensory Design, Joy Monice Malnar and Frank Vodvarka describe the different ways we encounter architecture.[8] We judge the scale of a building in relation to our own limbs and torsos. As we pass through a doorway, space hugs us tight and then lets us go. Air mutters through the HVAC system and ripples over our skin. Our feet pound against a building’s floor, and our hands grasp its railings and knobs. Our daily routines—cooking, cleaning, smoking, bathing—produce an embedded brew of smells that make inter-iors memorable. Windows puncture walls and expand space. Hansel Bauman, author of “DeafSpace,” notes that people who are deaf or hard of hearing use reflective surfaces to see what is happening behind them. Reflections duplicate space, creating visual echoes.

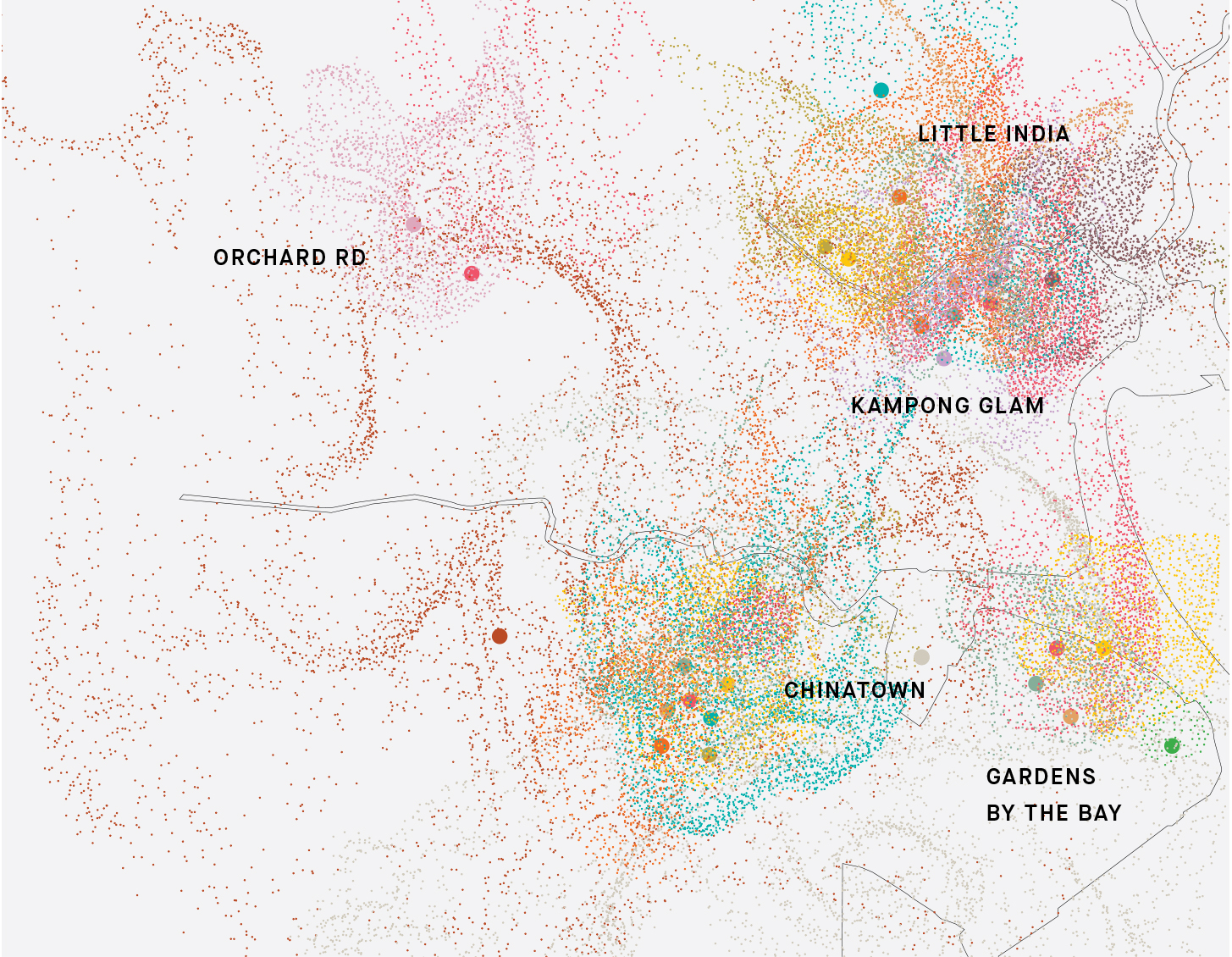

Sensory design celebrates the qualities of place. Graphic designer Kate McLean created a sensory map of Singapore using experiential data generated by over two hundred residents who went with her on “smellwalks.” Suspended in the humid air of this island city are the smells of curry, jasmine, and Manila rope. Little India and Kampong Glam are districts especially dense with scent. McLean’s map locates distinctive smells and visualizes their trajectories. Smell cannot be abstracted from bodily experience: “Using humans as sensors is a method that aggregates personal insight…. It is about the acceptance of the subjective as worthy and useful data.”[9]

Scentscape 06. 2015 – City of Singapore (detail), 2015; Kate McLean (British, b. 1965); 118.9

× 84.1 cm (46 13/16 × 33 7/64 in.); Courtesy of Kate McLean

Designers often find themselves at odds with the body. Modernism tended to favor hygiene and control over organic processes. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley chronicle the war between cool abstraction and the hot messy senses in their book Are We Human? Modern design served as an optical painkiller, an anesthetic that dulled the body by massaging the eye. Our modern obsession with smooth, slippery objects arose alongside the drugs invented to blunt pain in the age of modern medicine.[10] Whether banning ornament from architecture or barring friction from interfaces, designers often aim to make people feel less, not more. Don’t worry. Be happy. Teflon will calm your nerves and smooth your edges.

Body-numbing visuals saturate design culture. News feeds serve up glossy images of products and buildings that most readers will never meet up close. Museums embalm artifacts in climate-controlled pods of glass and plastic.[11] Design students learn to worship visual form and abstain from touching, smelling, and tasting. Vision crowds out the other senses. Looking trumps making. Digital artists Wang & Söderström create strange still lives populated with glistening, hyperreal artifacts simulated with digital tools.

(left) Treasures 3, 2016; Anny Wang (Swedish, b. 1990) and Tim Söderström (Swedish, b. 1988), Wang & Söderström (Copenhagen, Denmark, founded 2016); 3D software: 3Ds Max, Vray, Modo; Courtesy of Wang & Söderström. (right) TSS II Spoon, from the Sensory Dinner Spoon collection, 2016; Jinhyun Jeon (South Korean, b. 1981), Studio Jinhyun Jeon (Eindhoven, Netherlands, founded 2012); Maple; 2.5 x 2.6 x 13.2 cm (1 x 1 x 5 3/16 in.); Courtesy of Jinhyun Jeon

Touch borders on all the senses. Skin, the body’s largest organ, flows from the outside in at every port of entry: ears, eyes, nose, mouth, anus, and genitals.[12] The mouth and tongue embrace the chewy heat of charred meat or the buttery chill of ice cream. Filmmaker David McDouggal writes, “I can touch with my eyes because my experience of surfaces involves both touching and seeing.”[13] The eye strokes the contours of distant glistening bodies the hand can’t reach.

Sensory design confronts the body. Designer Jinhyun Jeon’s wooden dinner spoon embraces sensory knowing. Our hands measure the object’s weight and length. Our skin registers the material’s temperature and smoothness. Our fingers navigate changes in form, finding nuance in the bumps along the spoon’s edge and at the handle’s tip. Our ears prick at the muted clank when the spoon is placed on a tabletop. Our nose picks up the faint glow of lightly stained maple. Objects gain meaning and value in our embodied experience of them.

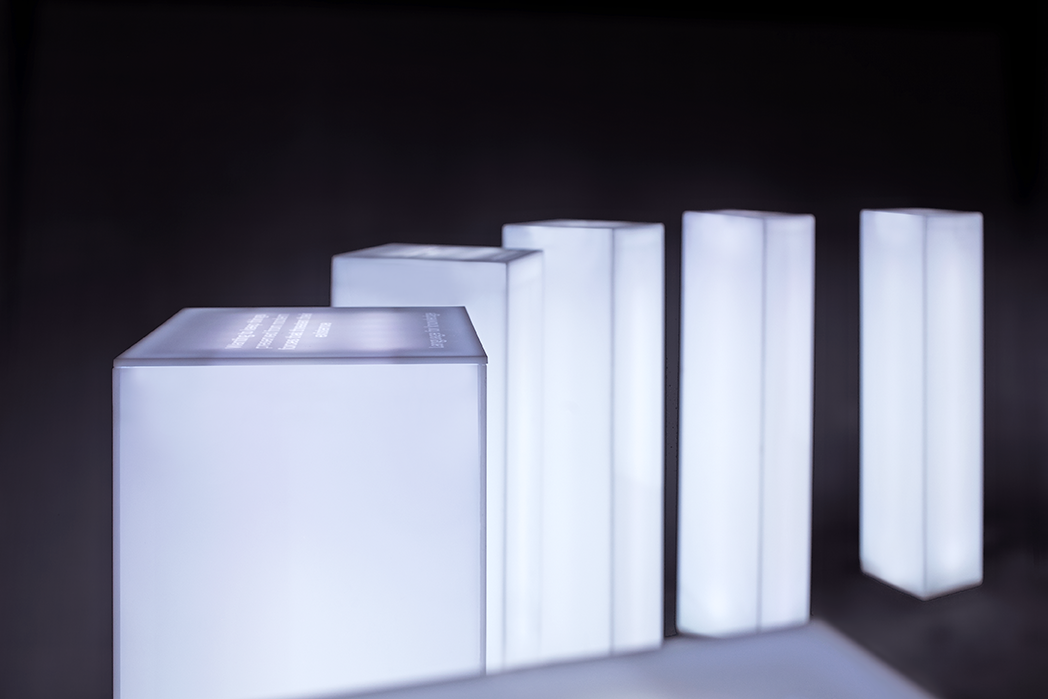

Sensory design has the power to forge new languages. In 2017 and 2018, IFF (International Flavors & Fragrances Inc.) partnered with Dutch design collective Polymorf to explore the role of scent in human interaction. They collaborated with Professor of Language, Culture, and Cognition Asifa Majid and senior perfumer Laurent Le Guernec to imagine an “invisible dictionary” of nuanced emotional states reflecting the complexity of modern life. Inspired by Majid’s research with indigenous communities such as the Jahai, who have developed an elaborate smell vocabulary, the project presents such uniquely contemorary emotional states as “a moment of collective déjà vu,” “the torment caused by the inability to act,” and “being perfectly entangled with another.” Le Guernec composed original scents using IFF-designed molecules to represent the feelings on display. Rather than offer literal or figurative depictions of these emotions, Le Guernec’s olfactory creations are abstract and sensorial—like language itself. In the installation, a series of translucent pedestals are softly lit from within. When activated by a visitor, each pillar diffuses a scent through a line of laser-cut text. Visitors, by connecting each named emotion with a special smell, begin to assimilate a new dialect.

Dialect for A New Era, Installation, 2017; Artistic Concept and Interface Design: Frederik Duerinck (Dutch, b. 1976) and Marcel Van Brakel (Dutch, b. 1970), Polymorf (founded Netherlands, 2003); Perfumer: Laurent Le Guernec (IFF); Scientist: Asifa Majid; Creative Direction: Jean-Christophe Legreves and Anahita Mekanik (IFF); Scientific Advisor: Sissel Tolaas; Plexiglass, metal interior, LED lighting, scent diffusion; Courtesy of IFF

Sensory design rubs up against the living-thingness of the world. A room is not just a cube punctured with windows and doors. It is a sensing creature with deep pockets and velvet shadows. It curves like an eyeball and bends like an elbow. The wool canyons of a blanket trap warmth. The folds of a curtain seize light and sound. A rug inhales noise; floorboards sigh with grief. Sensory design tweaks our skin, bones, and muscles. It tickles, pinches, and pops. It plays rough. It touches us, and we touch back.

Notes

[1] On perception as an active, purpose-driven, embodied process, see Andy Clark, Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). Michael Haverkamp applies the principles of Gestalt psychology to sensory design in Synesthetic Design: Handbook for a Multisensory Approach (Basel: Birkhauser, 2013).

[2] Richard E. Citowic, interview with Ellen Lupton, 23 February 2017. See also Richard E. Citowic, MD, and David M. Eagleman, PhD, Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

[3] Cytowic, interview. See also Nicola Twilley, “Sight Unseen: Seeing with Your Tongue and Other Surprises of Sensory-Substitution Technology,” The New Yorker, 15 May 2017, 38–42.

[4] Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (West Sussex, England: Wiley, 2005). For an updated account of sensory architecture, see Sarah Williams Goldhagen, How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives (New York: HarperCollins, 2017).

[5] Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, Inclusive Design Guidelines, 2nd ed. (New York City, 2017).

[6] James J. Gibson, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1966, 1983); Jan Lauwereyns, Brain and the Gaze: On the Active Boundaries of Vision (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012).

[7] David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: Vintage Books, 1997).

[8] Joyce Monice Malnar and Frank Vodvarka, Sensory Design (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004).

[9] Kate McLean, “Smellmap: Amsterdam — Olfactory Art and Smell Visualization,” Leonardo, 50, no. 1 (2017): 92–93, doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_01225.

[10] Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016).

[11] Museums did not always forbid sensory experience. See Constance Classen and David Howes, “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts,” in Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, ed. Elizabeth Edwards et al. (New York: Berg, 2006), 199–222.

[12] Ellen Lupton, Skin: Surface, Substance + Design (New York: Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum and Princeton Architectural Press, 2012).

[13] Quoted in Sarah Pink, Doing Sensory Ethnography (London: SAGE Publications, 2015).

2 thoughts on “Why sensory design?”

Carrol Bonadio on September 1, 2020 at 7:06 pm

I have recently started a website, the info you provide on this website has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

my blog california native garden design on March 3, 2021 at 3:19 am

Thanks , I have recently been looking for info about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?