Written by Jeffrey Mansfield

Set in picturesque Casco Bay in southeastern Maine, Mackworth Island is a peculiar knob of land. It is a place I have known since I was a child: to the Deaf community it is known for The Governor Baxter School for the Deaf, to the locals for its hiking trails and miniature faerie houses, and to the world as the setting of Mark Medoff’s Tony-winning Children of a Lesser God.

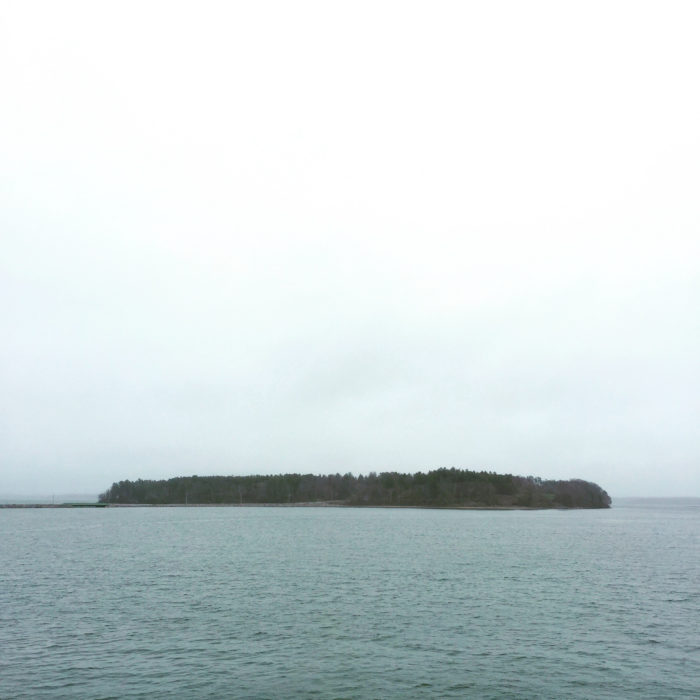

Mackworth Island, Falmoouth, Maine. Governor Percival Baxter deeded the island to the State of Maine in 1943 as a “sanctuary for wild beasts and birds.” Since 1957, the island has been home to the Governor Baxter School for the Deaf. Photo by author.

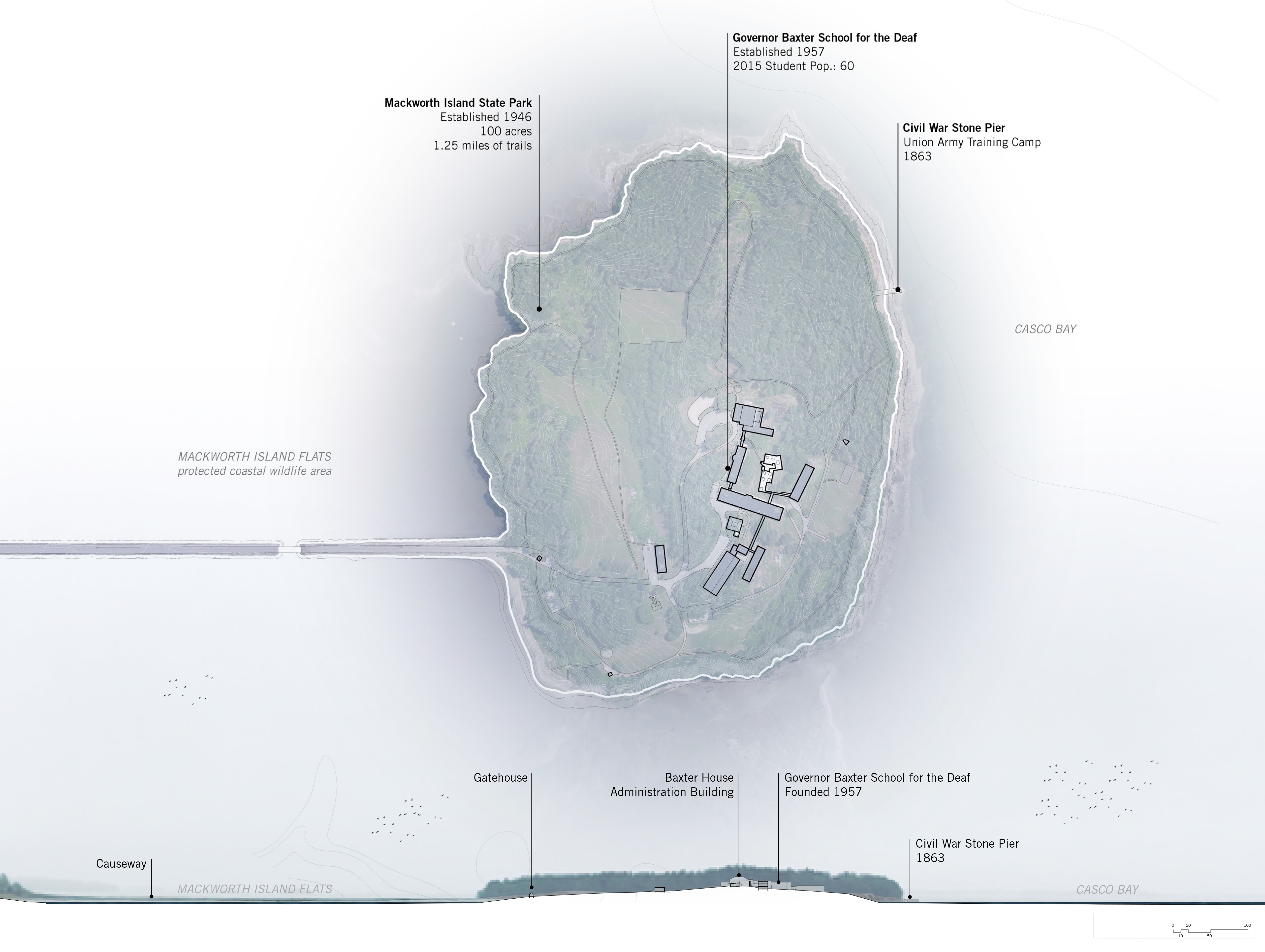

A residential school for the deaf founded in 1957 by deed of the late Maine governor, the school is a short drive from Portland. Yet, owing to its location on the 100-acre island, accessible only by boat or the causeway that connects the island to the mainland, the school could not be further from the city. Its topographical and bathymetric contours–precise yet arbitrary lines drawn by surveyors–also draw the contours of normalcy in our society, and in its inverse, dis-ability, designating a physical and mental boundary between ‘normal’ and the ‘other’. This edge condition obfuscates the island institution with other typologies of isolation, including the boarding school, asylum, prison, internment camp, hospital, lazaretto, leper colony, monastery, and sanctuary.

As a social institution, the mission of the deaf school was, historically, educational and rehabilitative: to prepare deaf children for productive assimilation into society. In the service of “curing” deafness, the architectural forms and vocabularies of deaf schools, from sprawling Kirkbride-like campuses to modern interpretations of the panopticon, bear therapeutic aims that forge an indelible link between deafness and pathology. Today, this merger continues to shape social attitudes towards deafness and guide technocratic approaches that seek to architect a final solution to the problem of deafness. But schools like Governor Baxter are subversive. For the first time in our lives, we were brought together and communication flourished effortlessly not through speech but through sign, challenging as a misdiagnosis the premise that deafness is an ailment. The deaf school did not so much cure deafness as cultivate a discrete, if disruptive, linguistic, sensorial, and material culture that resists the homogenizing effects of biopower. Most importantly, these schools brought transcendent dignity to Deafness.

Plan, Mackwork Island. A causeway connects the 100-acre island to the mainland; to enter the ecologically diverse island and the school, visitors must enter through a gatehouse–a symbolic threshold of our disciplinary society. Illustration by author.

Jeffrey Mansfield is an Associate with MASS Design Group, a Kluge Fellow at the Library of Congress, and holds a Master of Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Architecture of Deafness is supported with a grant from the Graham Foundation for the Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Deaf himself, Jeffrey attended a school for the Deaf in Massachusetts. This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Design Journal.