In last month’s Short Story, Jodi Rodgers discussed the drawings of Robert Frederick Blum and the purveyance of American drawing through the Cooper Union Museum’s collection. This month, we address the “Who is Cooper?” and “Who is Hewitt?” and “Why Carnegie?” questions that often accompany introductions of Cooper Hewitt’s name and location. We investigate and celebrate the relationship between the Hewitts and the Carnegies, two families that were instrumental in creating Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum as it is known today.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

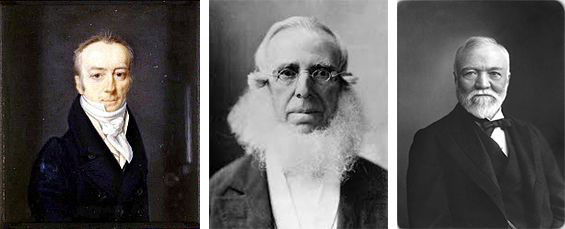

Three Tall Men

(left to right) James Smithson (1765–1829) by Henri-Joseph Johns, 1816; Peter Cooper (1791–1883); Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919)

Two great American philanthropists played a role in the creation of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Peter Cooper established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 1859 in which his granddaughters Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt opened a museum for the arts of decoration in 1897. In 1967, when the museum became part of the Smithsonian Institution, Andrew Carnegie’s mansion became its new home. An English philanthropist made it all happen. In 1829, chemist and mineralogist James Smithson left his fortune to the United States to found “an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge . . .” to be named the Smithsonian Institution. These auspicious connections are a good story.

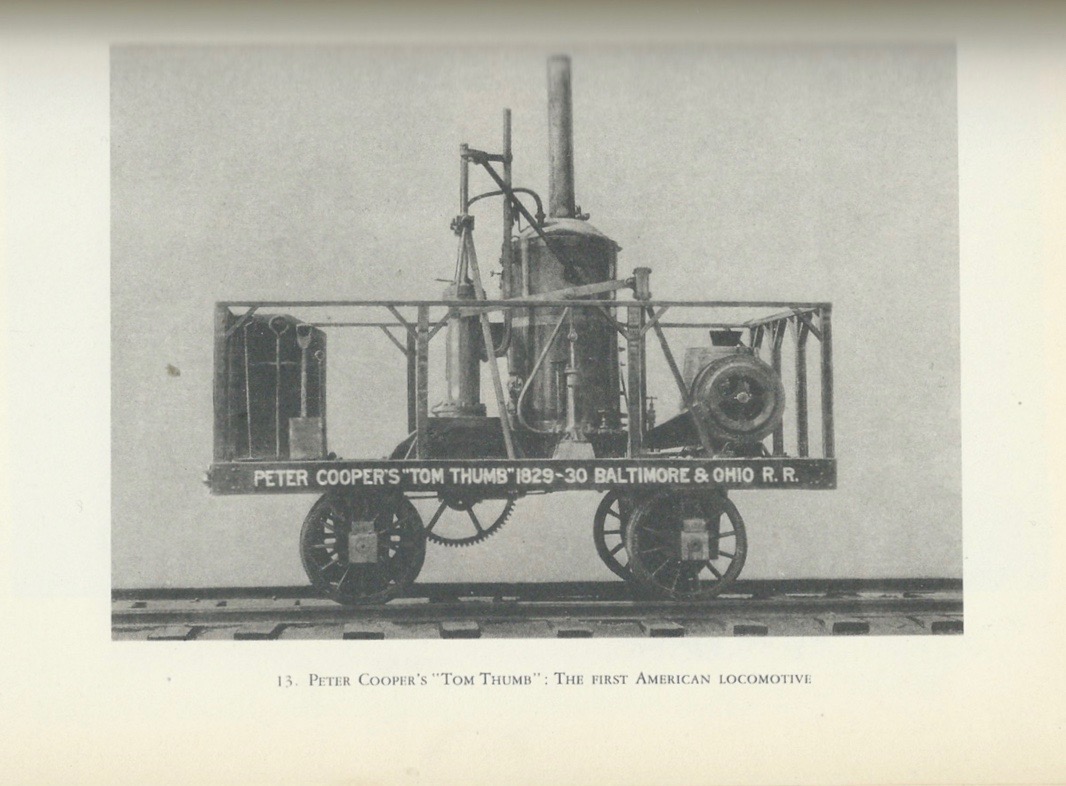

Remarkably the lives of Peter Cooper and Andrew Carnegie paralleled one another. Both Cooper and Carnegie were born poor with little formal education. A mechanical genius and inventor, Cooper initially made a small fortune in patents for glue and gelatin before moving on to design and construct the Tom Thumb locomotive in 1830. He began to amass real estate in New York City and pursued his interests in the manufacture of iron. Aware of his lack of knowledge, he wanted to provide a free educational institution for poor but ambitious young men and women.

Tom Thumb, designed and constructed by Peter Cooper in 1830

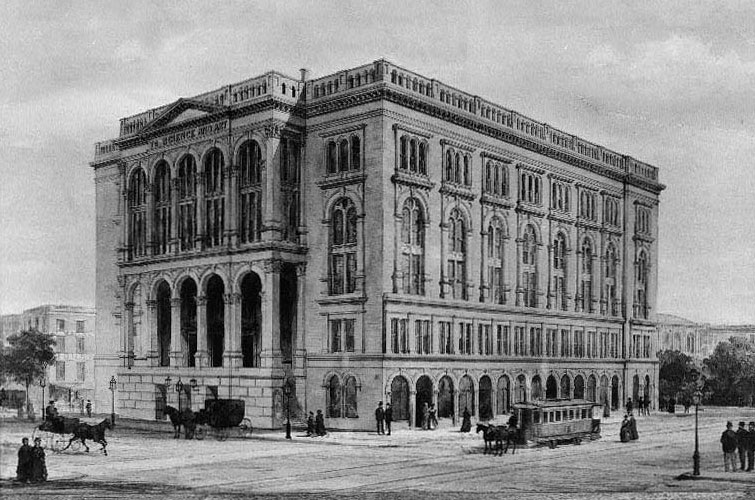

Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, also known as Cooper Institute

Born in Scotland, Andrew Carnegie’s education consisted of attending the local grammar school. As a young man, he developed a passion for reading and borrowing books wherever available. After his family emigrated to Pennsylvania, he began his career as a telegraph messenger boy, and with his work ethic and innate genius excelled in all that he tried, from railroad investments to building a fortune in the steel industry. In 1901, he formed the United States Steel Corporation, and in 1902 he moved into his new home at 91st Street and Fifth Avenue. With his great wealth, he embarked on a new career in philanthropy, highlighted by establishing public libraries throughout the United States.

Both Cooper and Carnegie believed in the responsibility of wealthy men to provide for the education of the poor. Carnegie famously wrote the Gospel of Wealth in 1889, citing Peter Cooper’s Cooper Institute as an example of using wealth to elevate the poor by giving them the means to improve their lives. They admired one another and became personal friends.

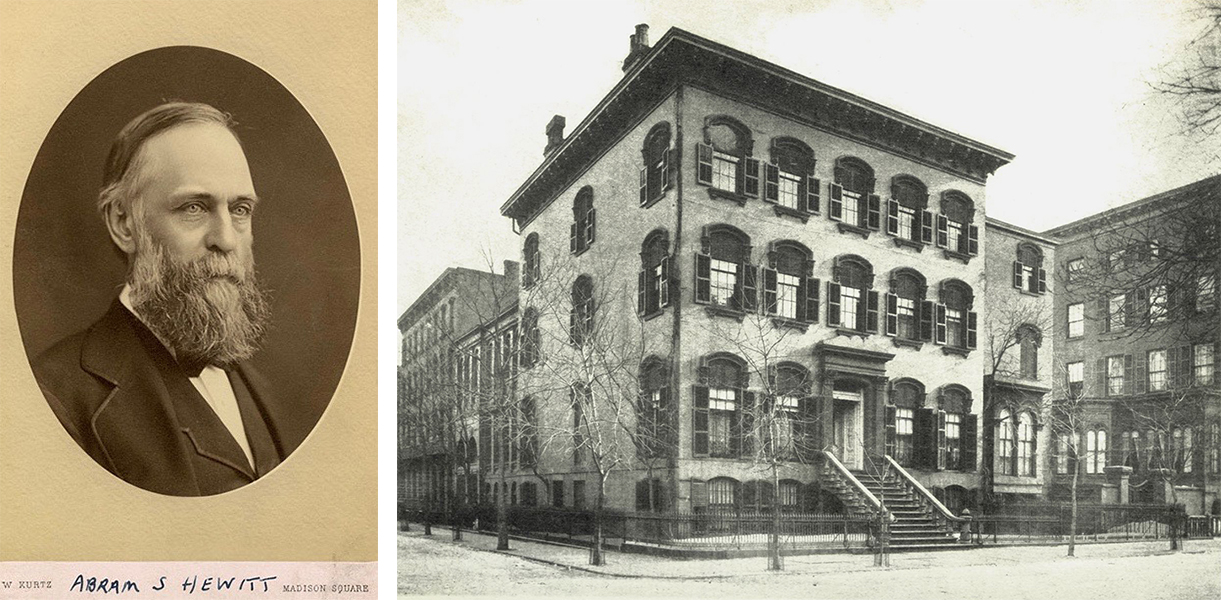

After Cooper died in 1883, Carnegie developed a relationship with Abram Stevens Hewitt, Cooper’s son-in-law. Hewitt (1822–1903) was a brilliant scholarship student at Columbia College and became successful in three different fields: the iron and steel business; national politics, serving five terms in Congress; and mayor of New York City. As a philanthropist, he was devoted to Cooper Institute and served as trustee of Columbia University, Barnard College, and the Carnegie Institution.

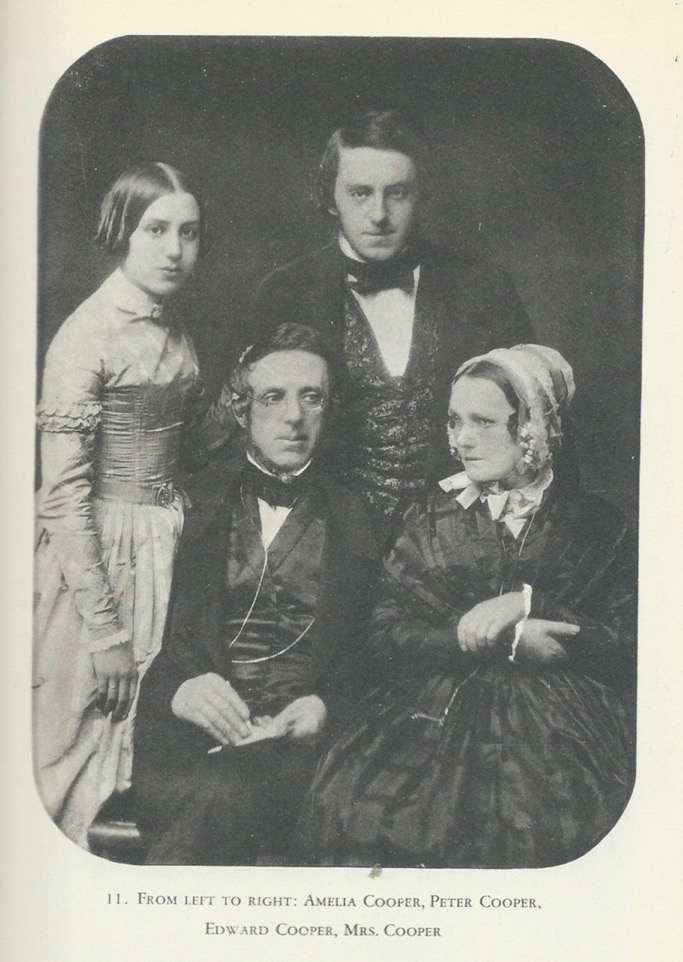

Peter and Sarah Bedell Cooper, with children Sarah Amelia and Edward

(left) Abram Stevens Hewitt; (right) 9 Lexington Avenue, New York, 35-room home of the Cooper-Hewitt family

In 1901, Carnegie made a gift of $100,000 to the Cooper Union, a testament to his admiration for Peter Cooper and Hewitt’s accomplishments for the Institute. Hewitt gratefully accepted this gift, telling Carnegie that it would be the beginning of a fund to benefit the Institute. When Carnegie realized that his gift was inadequate for the need, he replied, “I did not understand the case. Let me give $300,000.” (Equivalent to $811,000 in 2018). Not long after that, Hewitt and Carnegie met again, and, realizing the great financial requirement of the Institute, Carnegie gave an additional $300,000 on the condition that the Cooper-Hewitt families match this gift. And they did. These new gifts made it possible for the Cooper Union to enlarge their curriculum and increase the size of their facility. Additional gifts came to Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt for their museum, where Andrew Carnegie served as an advisor.

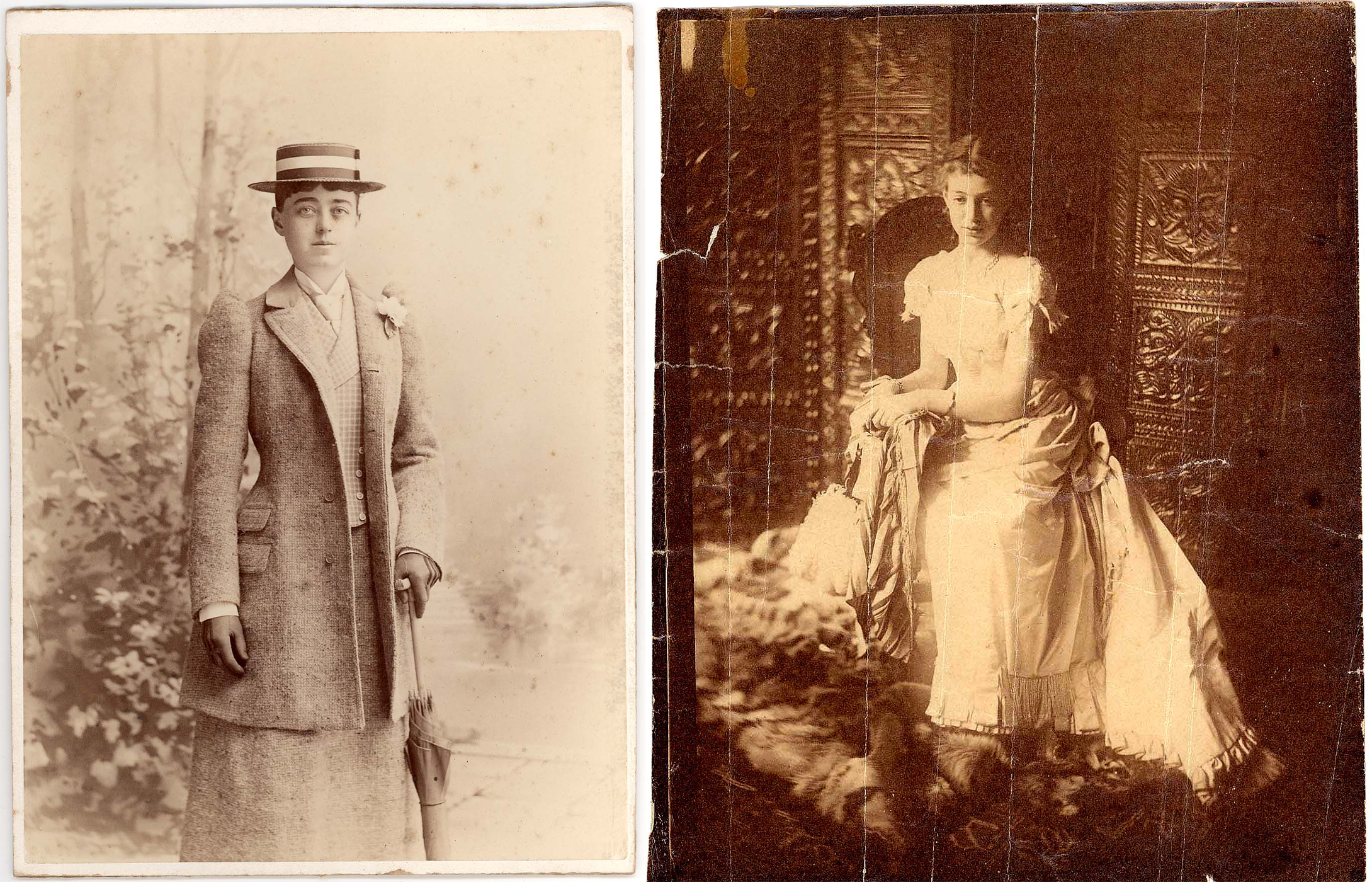

(left to right) Sarah Cooper Hewitt, ca. 1890; Eleanor Garnier Hewitt, ca. 1888; Both courtesy of Anna Engesser Parmee

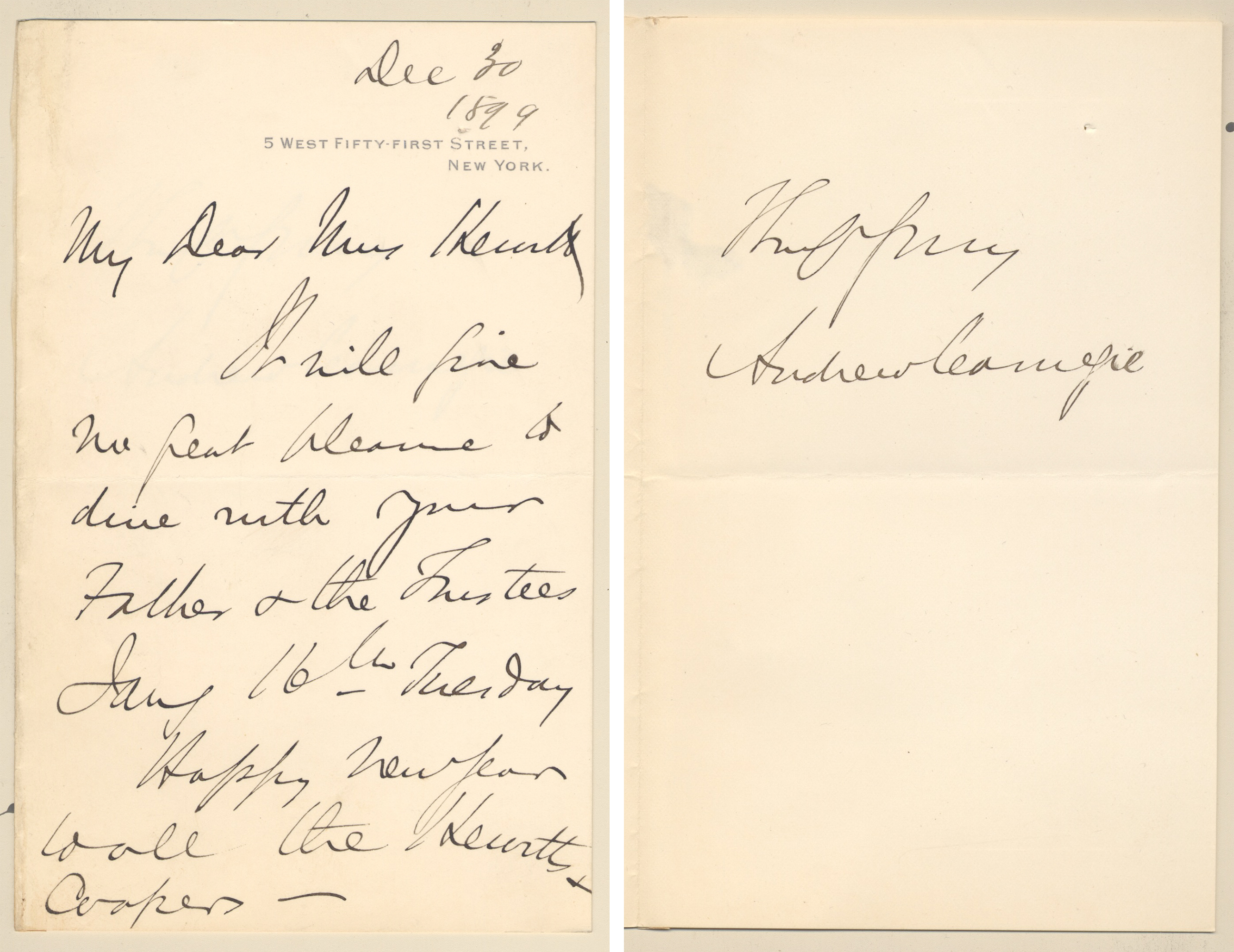

Note dated Dec 30, 1899, from Andrew Carnegie to Eleanor Hewitt, sent from his home at 5 West 51st Street, signed “Hogmanay”—a Scottish greeting for New Year’s Eve!

In 1963, decades after the leadership and support of the Hewitts, Cooper Union reported that it would disband the museum due to strained financial resources. After a few years of outcry and speculation, the Smithsonian agreed to steward the museum’s collection, creating the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, and the collection found a new physical home with a very dear friend.

A Mansion for a Magnate

While Carnegie served on the advisory council of the Cooper Union Museum, he also made one extraordinary, posthumous contribution to the museum’s legacy: his mansion! In 1972, Carnegie Corporation agreed to give the building to the Smithsonian for the sake of housing the collection of Cooper Union.

North and west facades of the Carnegie Mansion at Fifth Avenue and 91st Street in New York, 1903.

When the Carnegies—Andrew, Louise, and their five-year-old daughter Margaret—moved into their new mansion on New York City’s Upper East Side, the neighborhood was undeveloped territory. It was 1902—more than a century before Gossip Girl would have the area as her stomping ground—and fashionable society mainly congregated downtown (the Hewitt home was comfortably stationed sixty-nine blocks downtown of the Carnegies at Lexington Avenue and 22nd Street). But the Carnegies wanted space, light, and a private garden for Margaret, and thus purchased a number of large plots of land far uptown—eighty-six blocks uptown of Cooper Union, thirty-four blocks uptown of Carnegie Hall (completed in 1891)—at 91st Street and Fifth Avenue.

Construction occurred between 1899 and 1902. Babb, Cook & Willard was hired as the architectural firm, and Louise oversaw most of the design decisions that went into the home. The resulting four-style Georgian-style mansion is to this day a mammoth presence on Fifth Avenue. Visitors—then and today—approach the building by traversing the sweeping parkway to doors stationed beneath a fanning Tiffany canopy. Once inside, the modern visitor might even feel under dressed ascending the cavernous grand staircase, flanked with rich wood and enveloped by the warm glow of the Caldwell chandelier.

Grand staircase, photographed in 2002.

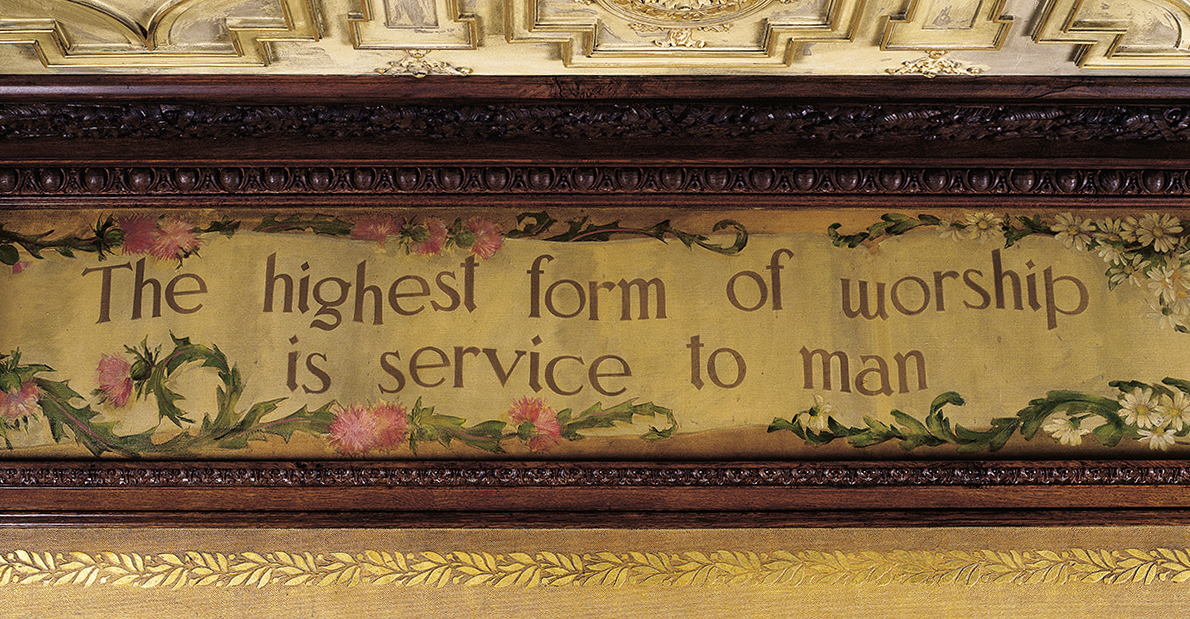

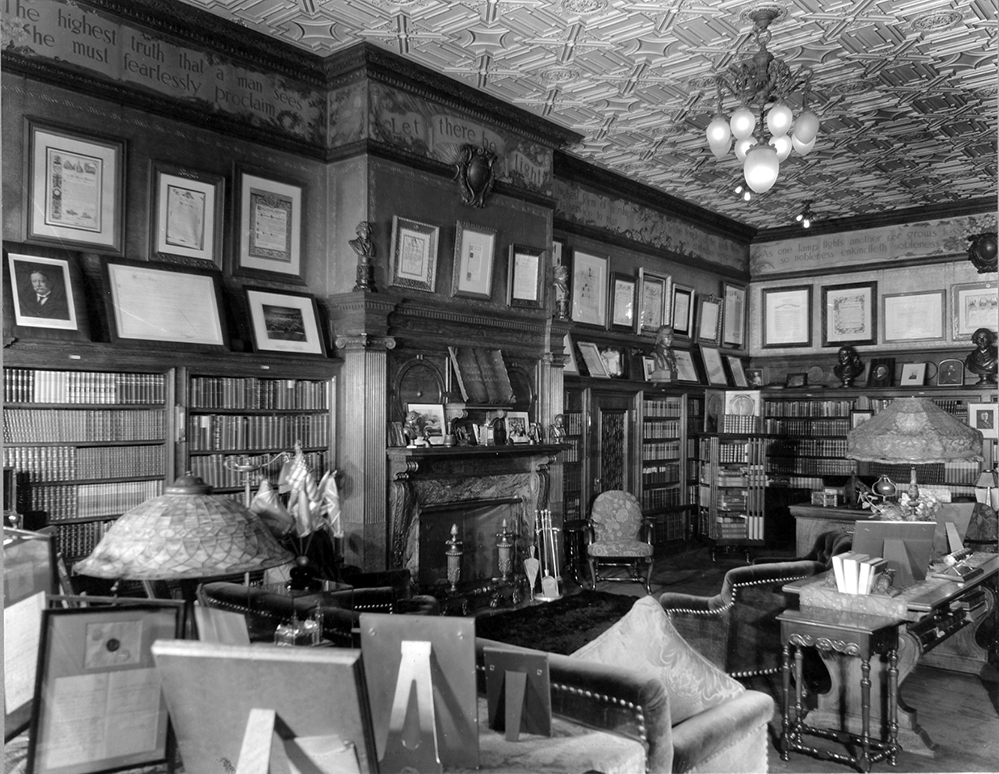

The mansion and Cooper Hewitt enter Carnegie’s personal history at a convenient moment. No longer the robber baron presiding over his namesake steel company, Carnegie Steel, Andrew was edging toward retirement in 1901 (or so he had promised Louise) and focusing on the charitable distribution of his immense wealth. Much of his philanthropy, particularly investing in the education of the working class, was directly inspired by Peter Cooper and educational model of Cooper Union. The decoration of his office reinforced this mission, with friezes by Elmer Ellsworth Garnsey preaching such themes.

Frieze in Carnegie’s library by artist Elmer Ellsworth Garnsey.

Carnegie’s library, 1911.

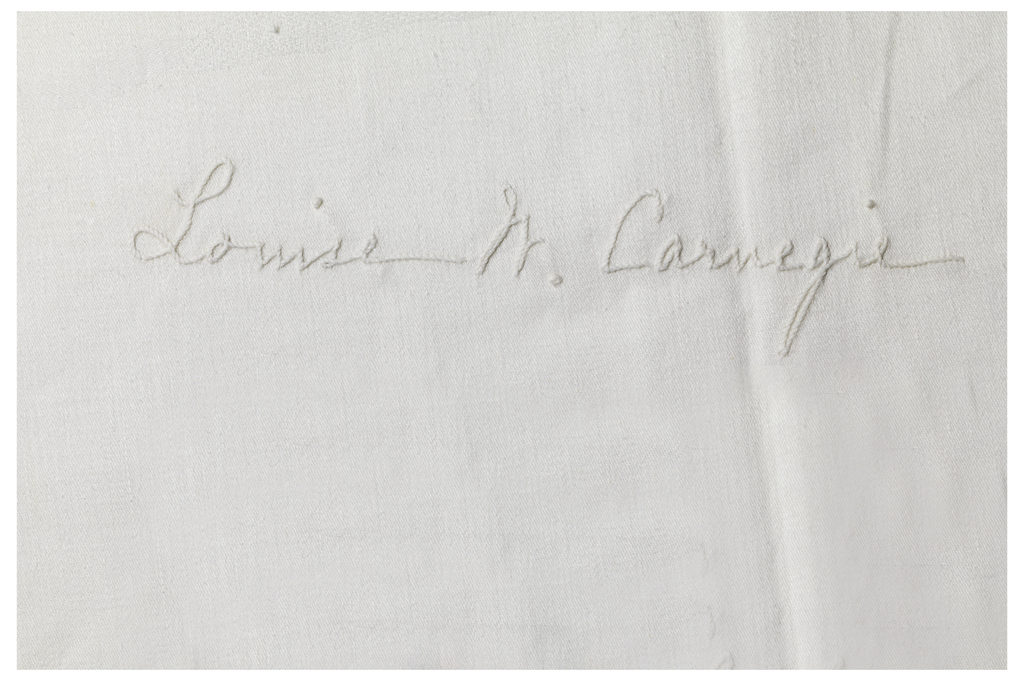

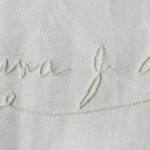

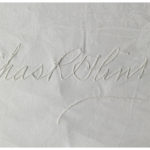

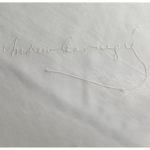

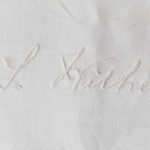

In addition to entertaining philanthropic interests, the Carnegies also entertained. In their stately residence, they hosted heads of state, scientific minds, and prominent cultural figures. Four tablecloths remain exquisite remnants of these festivities, two of which are in Cooper Hewitt’s collection. Guests would sign the tablecloth during dinner, and then servants stitched over the signatures, preserving them for history.

Louise Carnegie’s signature embroidered into a table cloth. Tablecloth (detail), late 19th century; Embroidered linen; Gift of Carnegie Corporation of New York, 1979-22-2-a

Carnegie’s Scottish heritage echoes throughout the interior decoration of the mansion. Much like a modern dad’s stuff might be emblazoned with paraphernalia of his favorite sports team, Carnegie’s stuff trumpeted his Scottish heritage. Lavish gilt details in the Music Room depict bagpipes. A goblet gifted to Carnegie from the Engineer’s Club of New York (now in Cooper Hewitt’s collection) is decorated with thistles. Additionally, acorns (a popular symbol of the self-made rich) are carved into the intricate woodwork around the building’s spaces.

(left) Goblet, 1907; Made by Tiffany and Co. (New York, New York, USA); Cast gilt bronze; Museum purchase from General Acquisition Endowment, 1985-76-1. (right) Detail of gilt molding in the Music Room of the Carnegie Mansion.

A balustrade detail on the second-floor railing of the grand staircase.

Possessions of the Carnegies’ and their daughter Margaret Miller have further enriched Cooper Hewitt’s collection. In 1977, Margaret wrote to Lisa Taylor, then director of Cooper Hewitt, regarding a prized lamp by Tiffany Studios: “I have a great fondness for this beautiful lamp and if you feel it would be of sufficient value to be in the Cooper Hewitt Museum I would be most happy.” The lamp has been proudly displayed in numerous museum exhibitions. Additionally, a Tiffany tea set decorated with chrysanthemums (a popular floral motif in the late nineteenth century) was owned by Margaret and her husband Roswell when they lived in a townhouse adjacent to the mansion’s garden.

(left) Dragonfly lamp, 1900–10; Designed by Clara Driscoll (American, 1861–1933); Design director: Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933); Produced by Tiffany Studios (New York, New York, USA); Stained glass, lead, cut brass, gilt bronze; Gift of Mrs. Margaret Carnegie Miller, 1977-111-1-a/c. (right) Chrysanthemum Kettle on Stand, 1891–1902; Manufactured by Tiffany and Co. (New York, New York, USA); Silver, ivory; Gift of Mrs. Roswell Miller, 1978-6-2-a/d.

Much of the Carnegies’ personal affects were auctioned off in 1949 after Louise’s death in 1946, which left ownership of the mansion to the Carnegie Corporation (Margaret had by then married and moved out). While it was not known at the time that the building would one day house the nation’s design museum dedicated to decorative arts and design, many of the lighting fixtures and wallcoverings were preserved. An assortment of these pieces are still installed throughout the mansion and the museum’s campus offering elaborate illumination.

Caldwell lighting fixture in the mansion’s Great Hall.

Fragment of wallcovering from Carnegie Mansion. Sidewall, ca. 1900; Stenciled canvas; Gift of Cooper-Hewitt Collection, 1974-102-1

Sidewall, 1900–01; Stenciled canvas; Gift of Cooper-Hewitt Collection, 1974-102-2-a/c

In 1969, fifty years after Andrew Carnegie’s death, the mansion was turned over to Smithsonian to be the home of Cooper Hewitt. Since Andrew, Louise, and Margaret first inhabited the Carnegie Mansion, the home has lived many lives, including the modern steward of the Hewitt sisters’ vision for their modern museum as Cooper Hewitt. The Carnegie family has continued its support of the museum, with Kenneth B. Miller (Andrew and Louise’s great-grandson) having served on Cooper Hewitt’s board, currently Chairman Emeritus.

For the complete history of the mansion, read Life of a Mansion: The Story of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, published by Cooper Hewitt. For more details on the interlocking stories that comprise Cooper Hewitt’s history, visit an illustrated timeline.

(Header image: detail of carved teak wood, designed by Lockwood de Forest and installed in the Carnegie’s family library, now the Teak Room at Cooper Hewitt.)

Sources

Ewing, Heather. Life of a Mansion: The Story of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (New York: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2014).

Letter to Lisa Taylor from Margaret Miller, March 30, 1977, in Cooper Hewitt’s archive.

Nevins, Allan. Abram S. Hewitt, With Some Account of Peter Cooper. Harper & Brothers, 1935.

Orr, Emily. “Gilded Goblet.” Object of the Day, April 20, 2016. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2016/04/20/gilded-goblet/.

Thompson, Hana. “Chrysanthemum Tea Set.” Object of the Day, October 27, 2012. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2012/10/27/chrysanthemum-tea-set/.

One thought on “Cooper Hewitt Short Stories: The Hewitts & The Carnegies”

Barry Drogin on November 4, 2018 at 12:41 am

Peter Cooper was never a robber baron. He wasn’t pro-union but treated his employees very well, he naively backed Tammany Hall, and he cornered the glue market through superior product and some shrewd business practices, but nothing that was comparable to his contemporaries or those who came after. It is true that many robber barons helped fund the Cooper Union after Peter Cooper’s death, but this shouldn’t reflect back upon Peter Cooper himself, or upon Abram Hewitt.