Written by Sarah Williams

Sarah Williams is the Director of Civic Data Design Lab and Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Technology at MIT. This article was originally published in Cooper Hewitt’s Design Journal Winter 2018.

Autonomous vehicles, electric cars, and ride-sharing applications are disruptive innovations that hold unknown outcomes for society. Future forecasters suggest these technological advancements will produce clean, efficient neighborhoods for our overly congested cities. At the same time, it is also predicted that certain innovations, like automated vehicles, will lead to job losses and serious changes to the cities’ economies. In reality, both outcomes are equally possible, which is why “We the People” must own the future of our cities and the data that powers that future.

Car companies Bosch and Daimler offer a future vision of the city with autonomous vehicles. © Daimler AG

The public has already started to lose control of the digital city. This is because the data generated by and used to operate civic technologies is largely owned by private companies. Automobile ownership is a great example of our predicament. Car owners may own their vehicles, but they do not own the software that makes the vehicle function. The software is only licensed to the owner. This is true for much of the tech we use every day. Think about your computer or cell phone. The operating systems for these objects are licensed. Some proponents of open-source software say we are held hostage by these licenses because we cannot own them outright. The same logic applies to city infrastructure, which is increasingly digital and generating massive amounts of information about our every movement.

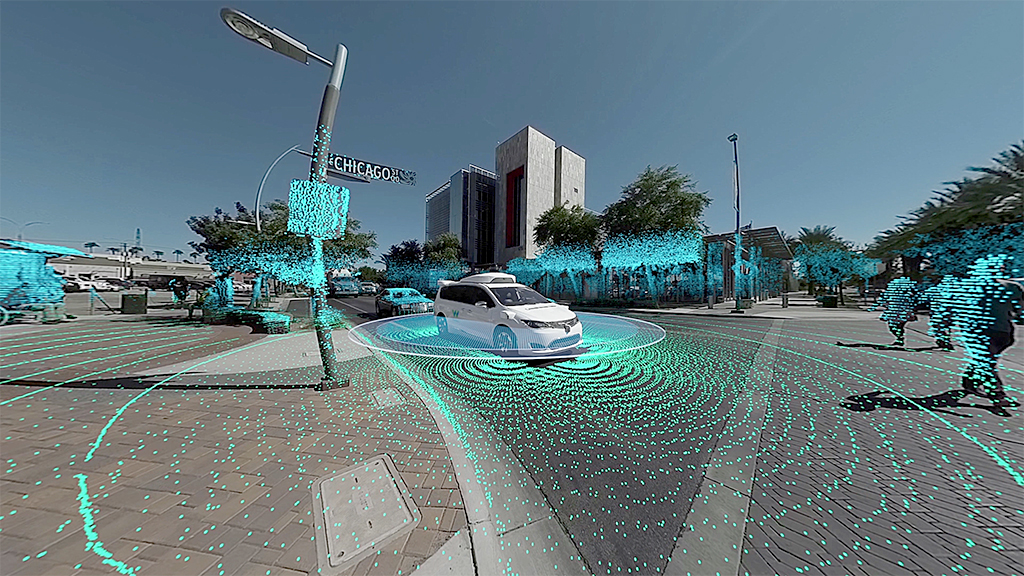

As an example, Waymo, Google’s autonomous vehicles program, has logged over 5 million miles of driving data. A single autonomous test vehicle produces about 30 terabytes per day, which is 3,000 times the amount of data Twitter produces daily. This data is stored and used to improve the algorithms needed to make autonomous vehicles function. Programmers at Google also use this data to construct digital representations of the physical world on their servers, which the autonomous vehicles use to guide their pathways on the road. Auxiliary data—obtained from security cameras and personal data, such as credit card purchases—can help construct and predict our daily movements. When this data is added to that digital world created for the car, it can be used to personalize our driving experience.

In this highly evolved virtual environment, autonomous vehicles—or any robot for that matter—are guided where to turn, stop to pick up a passenger, or come to a halt for a pedestrian to cross the street. Now imagine that you want this digital world to be smarter. Not just a 3D rendering of what you’ve done or where you’ve been, but predictive of what you might do in the future. Having captured your buying habits and movements, this data can be mined to identify, for instance, when and where you might want to buy a quart of milk, and your car programmed to remind you to do it. Adding this type of information to the autonomous vehicle’s database allows the car to make decisions based on your behavior.

Augmented reality might come before autonomous vehicles—the virtual infrastructure already exists, demonstrated by WayRay’s holographic AR head-up display. Courtesy of WayRay AG, wayray.com.

This alternative reality—really a new digital reality—will be the infrastructure of the future. We will tap into it to perform all kinds of tasks. Much in the same way networked computers created the World Wide Web, this environment will power many innovations created by those who have the capabilities to tap into it. Right now, that ability lies solely with the companies who generate the data, like Waymo, Tesla, Ford, and others experimenting with autonomous vehicles.

Companies are already using their virtual worlds to create diverse products beyond the car. Google has developed an augmented reality navigation tool for your smartphone, fueled by this digital environment. Microsoft has started to use some of this data to create a product it calls 3D Soundscapes, which taps into the virtual environment to help a person with vision loss navigate through the city. The applications are almost endless. Therefore, it is essential that the public has a say in regulating this new digital infrastructure. The same way infrastructure innovations of the twentieth century, such as sewers and power lines, are now regulated by government.

Three-dimensional environment created as a Waymo car moves through the city. Courtesy of Waymo.

How can we assert some kind of control over this new infrastructure when it is largely owned by private companies? In 2017, an international consortium of NGOs and city and transport organizations created a set of principles for governments and corporations to ensure best outcomes as mobility innovation advances. The consortium explicitly affirms data and the systems created from data as a “public good,” stating that the “physical, digital, and financial access to shared transport services are valuable public goods and need thoughtful design to ensure use is possible and affordable by all ages, genders, incomes, and abilities.” Public goods are commodities or services provided without profit for the greater good of society. The digital world created by autonomous vehicles will be a public good because our future society will need this digital reality to power civic infrastructure.

The argument that data is a public good is controversial, as private companies have set up entire businesses to extract value from this data. Uber, for one, claims giving away its data is equivalent to giving away its business. While Uber has shared some of its data, this information is not much different from that which cities already collect. Individual trip data would be more valuable, because analysis of the minute-to-minute working of a city can go a long way toward identifying causes of congestion. Given that Uber is operating on our public infrastructure—using our roads, bridges, and tunnels—isn’t it obligated to return the data collected back to the public? I believe cities should enforce data-sharing agreements when private companies use public infrastructure for profit. The same logic applies to autonomous vehicles: while the car companies create the alternative reality that makes these cars work, they are operating these vehicles on public infrastructure.

Cities still have the upper hand to negotiate better deals for working with private companies that are developing civic infrastructure. Moreover, it is imperative that city leaders use their authority, as many cities derive fifty percent of their budget from mobility-related fees—everything from parking violations to bridge tolls. Cities should leverage the popularity of these new systems by charging taxes to subsidize autonomous vehicle use in neighborhoods that have high levels of poverty. Regulations also have to be considered to recover the cost of the using the city’s infrastructure, such as charging fees for drop-off and pick-up zones, developing new taxes for empty seats in vehicles, and establishing fees for parking empty fleets. Some cities have begun to question whether autonomous buses should be run by the government or private companies. The public must put guidelines in place for autonomous vehicles now, before we relinquish all control to private companies.

Public control has already been lost in some states, most notably Virginia. The state declared it will not regulate autonomous vehicles in order to attract the business of autonomous car companies, which the government hopes will stimulate job growth and other economic benefits. Some state governments also do not want to allow cities to create their own regulations. For example, Michigan’s state government passed legislation that limits Detroit’s ability to make its own rules about driverless cars. In New York, Governor Cuomo and Mayor De Blasio often fight about ride-sharing regulations. City and state governments must begin working together to manage the economic trade-offs generated by new technologies.

As we stand at the precipice of this exciting digital revolution, urban planners must take control of this new digital infrastructure and make sure it is available to all people. There are still many critical questions to answer to ensure the services derived from data are equitable so that everyone can benefit from the exciting new future of the digital city.