In ancient Greece, air (along with earth, water, fire, and aether) was one of the five elements thought to comprise all substances. Questions of air quality began to arise in the Middle Ages, even before the composition of the atmosphere was discovered.[1] In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as coal became deeply entrenched in both the economy and the environment, the problem became more urgent. Fossil fuel powered steam, and later electricity, drove trains, and heated homes—while also spewing smoke and smog. Meanwhile, scientists worked to improve air quality, mostly addressing occupational needs. In 1823, for example, Charles and John Deane designed a Smoke Helmet for firefighters to combat smoke-induced suffocation; in 1854, John Stenhouse developed a wood-charcoal-filter mask to protect miners from noxious fumes. Stenhouse’s mask was updated in 1871 by the physicist John Tyndall, who added a cotton filter saturated with charcoal, lime, and glycerin.[2]

While these devices improved respiration at the individual level, they did little to enhance environmental air quality. The first technology to do so was developed during World War II with the creation of the HEPA—or high efficiency particulate air—filter.[3] A joint project of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Army Chemical Corp, the HEPA filter was conceived to guard soldiers and scientists, especially those working on the Manhattan Project, from radioactive particles. While failing to reduce the harmful impact of radiation, HEPA filters offered effective protection from mustard and chlorine gasses. In the postwar period, as manufacturers retooled their factories from war- to peacetime production, HEPA technology allowed for the commodification of air purifiers. The 1960s witnessed both commercial and political progress in the field of air purity.

One researcher dedicated to the field of air purification was physician Alvan Barach, dubbed by his colleagues the “father of oxygen therapy.”[4] In the late 1950s, Dr. Barach collaborated with William Hall, a designer at Donald Deskey Associates, to develop a domestic air purifier. Their design passed air through an electrostatic field and filter, then alternately humidified and dehumidified it before recirculating the treated air back into the environment. The Barach-Hall air purifier was patented in 1961, and specified a device 3 ½-feet wide, 3-feet tall, and 20-inches deep. The DDA air purifier designs in Cooper Hewitt’s collection show that the firm worked out concepts for both vertically- and horizontally-oriented devices.

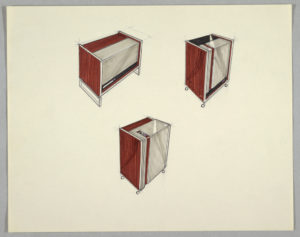

The drawing featured in this post belongs to a trio of polished renderings attributed to Earl (Bud) Hoyt, and which indicate that the horizontal concept prevailed. Here the air purifier formally adheres to the boxy rectilinearity typical of the 1950s. Supported by a nearly invisible base, the machine’s sides, rear, and front panel would likely have been constructed of prefabricated plywood or laminated with a wood-grain finish; at the top, two perforations function as handles for transportation between rooms. A beige, likely metallic, housing conceals the purifier’s mechanisms. These are controlled by buttons at upper right and accessed by a hinged front panel: in the drawing, this is likely the outlined section at front left. Hoyt has styled the device as a piece of modern case furniture, providing a neutral display space for bibelots, in this case colored glass vases. Although we know that in the 1960s DDA sold the rights to the Barach-Hall Air Purifier to J. H. Emerson Company (founded by Barach’s peer and collaborator Jack Haven Emerson) it is unclear whether these designs were ever produced. [5]

In 1963, two years after the Barach-Hall air purifier was patented, Klaus and Manfred Hammes developed the first air purifier intended for domestic use; that same year, U.S. Congress passed the Clean Air Act, which set fuel emission standards with the aim of reducing environmental air pollution. Concurrently, advancing research on respiration revealed that allergy and asthma sufferers alike benefitted from air purifiers.[6] Today, air purification remains a primary concern as we work to mitigate the global problem of worsening air quality that has resulted from years of under- or unregulated production and unfettered pollution. The air purifier at once represents industrial design’s potential to improve life and, more soberingly, the harmful impact of its byproducts on our wellbeing and environment. Fortunately, scientists and designers alike continue to work toward solutions that will allow us all to breathe a little easier.

Rachel Hunnicutt is an MA candidate in History of Design and Curatorial Studies at Parsons School of Design and a cataloguer in the department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt.

[1] See Peter Brimblecombe, “Attitudes and Responses Towards Air Pollution in Medieval England,” Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association 26, no. 10 (1976), 941-945. In the seventeenth century the existence of air pressure was proven and the ability to measure it developed. In the 1770s a series of advances led to the isolation and identification of oxygen gas.

[2] For further reading on the evolution of the gas mask, see Vincze Miklós, “An Illustrated History of Gas Masks,” io9.Gizmodo.com, May 13, 2013, https://io9.gizmodo.com/an-illustrated-history-of-gas-masks-504296785

[3] The acronym HEPA was applied to the invention retroactively by a U.S. Department of Energy official in the 1960s. HEPA filters function by physically trapping airborne contaminants, while on the other hand ionizers emit charged particles that bond with contaminants, weighing them down and preventing them from circulating with an environment’s clean air.

[4] Peter B. Flint, “Dr. Alvan Barach, Breathing Expert,” The New York Times, December 14, 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/12/14/archives/dr-alvan-barach-breathing-expert.html

[5] Emerson is best-known for his improvements to the iron lung in the 1940s, widely used to treat polio patients until the vaccine was developed in the late ‘50s/early ‘60s; Emerson’s innovation was spurred by a suggestion by Barach, and the pair went on to jointly develop an automated cough machine for neuromuscular disease patients.

[6] Asthma was historically considered a psychological disorder and was only acknowledged as a medical condition in the mid- to late twentieth century, concomitant with the rise of the domestic air purifier.