This week’s posts feature case studies from Cooper Hewitt’s Digital Collections Management Project, a conservation survey of born-digital and hybrid objects in the permanent collection. The two-year project was coordinated by an in-house team of conservators, curators, and registrar, and was conducted by digital conservation specialist Cass Fino-Radin and his team at Small Data Industries.

Background: This case study focuses on documenting and preserving interfaces in consumer electronics. The Motorola Envoy, introduced in 1994, holds a highly important place in Cooper Hewitt’s collection—of all of the handheld personal electronic assistants and devices in the museum’s holdings, this one best explains the origins of smartphones. This story is told only in part by the Envoy’s physical form—the heart of the story lies within its software and operating system: Magic Cap.

The Magic Cap software and operating system (OS) were designed by a pioneering firm called General Magic, founded with the explicit purpose of inventing the future of personal handheld electronic devices, or as they called them, “personal intelligent communicators.” General Magic’s ideas were highly speculative for their time—even bordering on science fiction. While some of their designs led to commercial flops and the company dissolved (in 2002), today, these failures are widely regarded as the ideas that would go on to inspire the entire contemporary paradigm of smartphones and electronic wearables such as smart watches.

Other than the Envoy’s lack of a cellular connection for making phone calls on the go, and its lack of a camera, the Magic Cap OS and its integration with network service providers such as AT&T and AOL allowed users to do nearly anything that you can do on current-day smartphones: download apps, get directions, check the stock market, check flight information, and use spreadsheets.

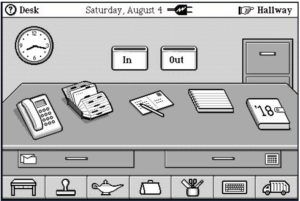

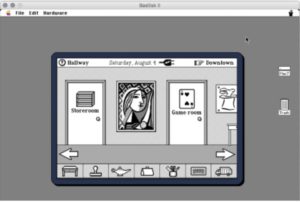

In the Magic Cap OS, users were presented with an entire world of skeuomorphic design—most operations could be conducted from the user’s “office,” where there was a clock on the wall, an inbox and outbox, and a desk with a rolodex, telephone, notebook, and calendar. Each of these served merely as icons for fully functional versions of exactly what one would expect on a contemporary smartphone today. Thinking forward to how to display the Envoy in the future, finding a way to show the interface should be prioritized. This case study describes two different approaches: simulation vs. a more costly emulation strategy.

Condition assessment: When Cooper Hewitt acquired the Envoy in 1995, no accompanying power supply, manuals, memory cards, or accessories were included with the object itself. The Envoy serves as an ideal case study in the complexity of collecting consumer electronics: there are three fundamental categories of material that could be considered: software, hardware, and product design. The product was designed by frogdesign. The software stored on its Read Only Memories (ROMs) and displayed on its screen was engineered and designed by General Magic. Lastly, the hardware (from the CPUs themselves to the overall hardware design and engineering) was the invention of Motorola. This amalgamation of specialist companies truly collaborating on different dimensions or layers of design—in a manner that extends beyond mere supply chain practicalities—is hardly unusual in today’s landscape of industrial design of personal computers and devices, and frogdesign has been at the center of many of these collaborations.

In this case, some aspects of the design and inner workings of the object could not be known without opening up the device. But getting inside required potentially damaging the housing and/or internals– how could we practice before working on the collections object? On ebay, Small Data Industries was able to find a complete Motorola Envoy with all its related packaging, peripherals, and documentation. This second substitute object could be used for testing to give us a better sense of what was inside, and how to preserve the Envoy in the Cooper Hewitt collection.

Unfortunately, there are presently no existing emulators (tools which simulate a hardware environment, and can run outdated software) for the Motorola Envoy. If we were to create one, it would be a logical choice to build it within the MAME emulator platform, which is widely regarded for its rigor in implementation and dedication to accurately reproducing the functionality of specific vintage hardware. We engaged some of the maintainers of MAME in a conversation in an IRC chatroom (their chosen forum for discussing the MAME project) about what one would need in order to implement the Motorola Envoy. We were told that a good start would be dumps of the Envoy’s ROM chips, and very good photos of the circuit board—ideally schematics. We set about to fully disassemble the ebay Envoy so that we could investigate the viability of ROM dumping and schematic creation.

Reverse engineering the Envoy purchased on ebay allowed us to inspect the internal components of the device. While there is a certain intuition to consumer electronics disassembly, a ribbon cable was in fact damaged in the process. Inside, the PCB (printed circuit board) turned out to be double sided, meaning that there would be no way of creating a schematic other than doing a complete teardown. Additionally, there are, to the best of our knowledge, no methods of dumping the contents of 56 lead TSOP ROMs without fully desoldering and removing them from the PCB—a process that, due to the fine electronics on this board, is likely to be destructive, and unlikely to be reversible, two important principles of conservation ethics when working with museum objects.

What did we learn?: While Small Data located a service available in the Shenzhen province of China (presently the electronics manufacturing capital of the world) that will not only dump the ROMs of the Motorola Envoy, but also provide a complete schematic of the circuit board, and bill of materials, this process would be completely destructive. In order to get this information, each and every single electronic component would be desoldered from the circuit board, carefully cataloged, and then the board will be scanned, and then sanded down to reveal its next layer of circuit paths, scanned, sanded again, and so on.

Another approach, to simulate the software on another platform, led us to discover that General Magic had produced a few methods of running Magic Cap on desktop computers—seemingly for testing purposes. Small Data was able to source a copy of the Magic Cap Simulator for Mac OS 7, and have extensively tested it, running in the Basilisk II emulator. Based on this, we think that it holds some promise in serving a role as an interactive display for exhibitions. This recommendation comes with two important caveats.

- First: The Magic Cap simulator is just that—a simulator. No effort has been made to emulate the CPU of the Envoy so although the graphics and interactivity both function identically to the original hardware, everything loads very quickly. This does not create any problems per se, however, we feel it important to note this difference. General Magic explicitly designed for slow processing and load times on the Envoy, and went so far as to design an elaborate loading animation showing, instead of an hourglass or wrist watch, a magician’s magic hat spinning in a circle.

- Second: The Magic Cap simulator running inside a Mac OS 7 emulator solves only the issue of the ability to interact with the software, leaving the product design out of the picture.

The second Envoy from ebay was used to help inform the technical condition assessment, and provides the possibility of two different display options: either display the duplicate (powered on, touchable) or sacrifice it to collect the information to make a more accurate emulator (vs. simulator.

Going Forward–Simulation or emulation? Planning for interactive display: Selecting interactive hardware to enable this display would require finding a resistive touch screen, and ensuring proper size, resolution, and color. Also, some means of masking the screen, or otherwise ensuring the simulator fills the screen, must be devised, as otherwise it runs windowed with Mac OS 7 as seen below.

Displaying the Magic Cap simulator in an interactive display has promise, but will require collaboration between a technical expert and time-based media conservator to ensure the stability of the technology and aesthetic integrity of the overall user experience, which may be better served by investing the time and energy in creating an emulator.

Cass Fino-Radin is founder and lead conservator at Small Data Industries, a lab dedicated to supporting and empowering people to safeguard the permanence and integrity of the world’s artistic record. Before founding Small Data, Fino-Radin served as a time-based media conservator at MoMA, and Rhizome.

The Digital Collections Management Project was made possible with the generous support of the Collections Care and Preservation Fund of the Smithsonian Institution.