In celebration of World Pride, June Object of the Day posts highlight LGBTQ+ designers and design in the collection.

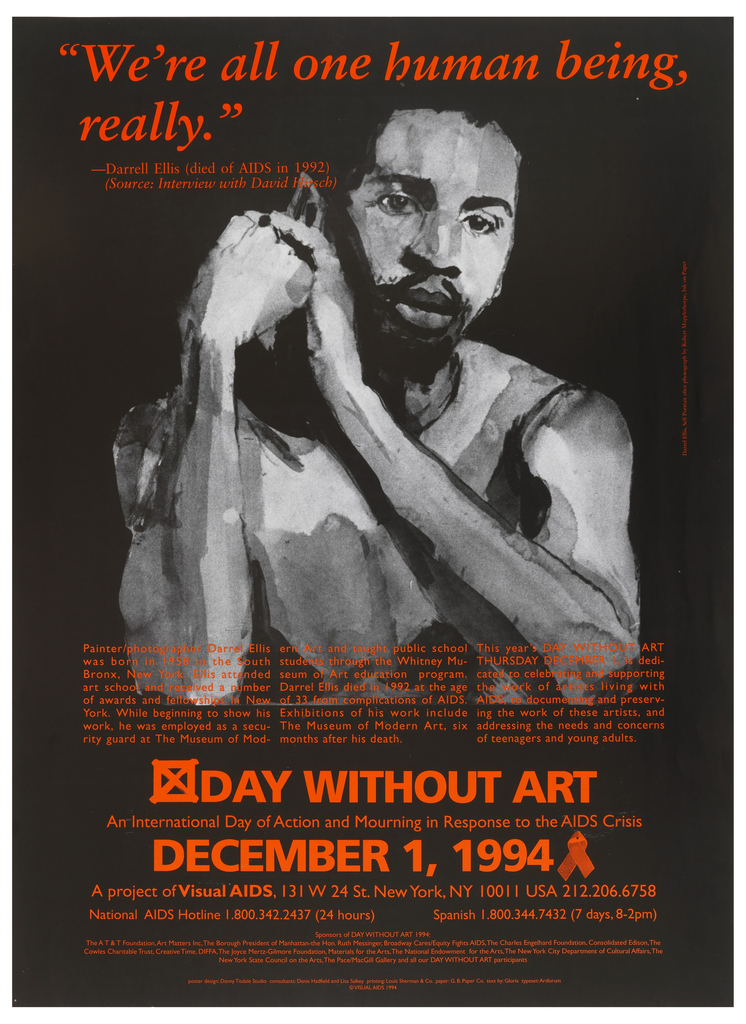

This poster, published by Visual AIDS in 1994, features a painting by Darrel Ellis (1958–1992), an African-American artist who created photographs, paintings, and mixed media sculptures. Many of his paintings are based on photographs, including family pictures taken by his father, Thomas Ellis, who was killed by police shortly before Darrel was born.

One of Ellis’s best-known works is featured in this poster. It is a self-portrait painted from a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. Ellis’s gentle, mournful expression and crossed arms suggest both vulnerability and strength. Mapplethorpe, a hugely successful white photographer, often produced images of young men of color who were less economically and socially secure than himself. In creating this painting, Ellis took back Mapplethorpe’s portrait and made it his own. Ellis’s black-and-white brushwork preserves a crucial element of photography while making a gestural, deeply personal image.

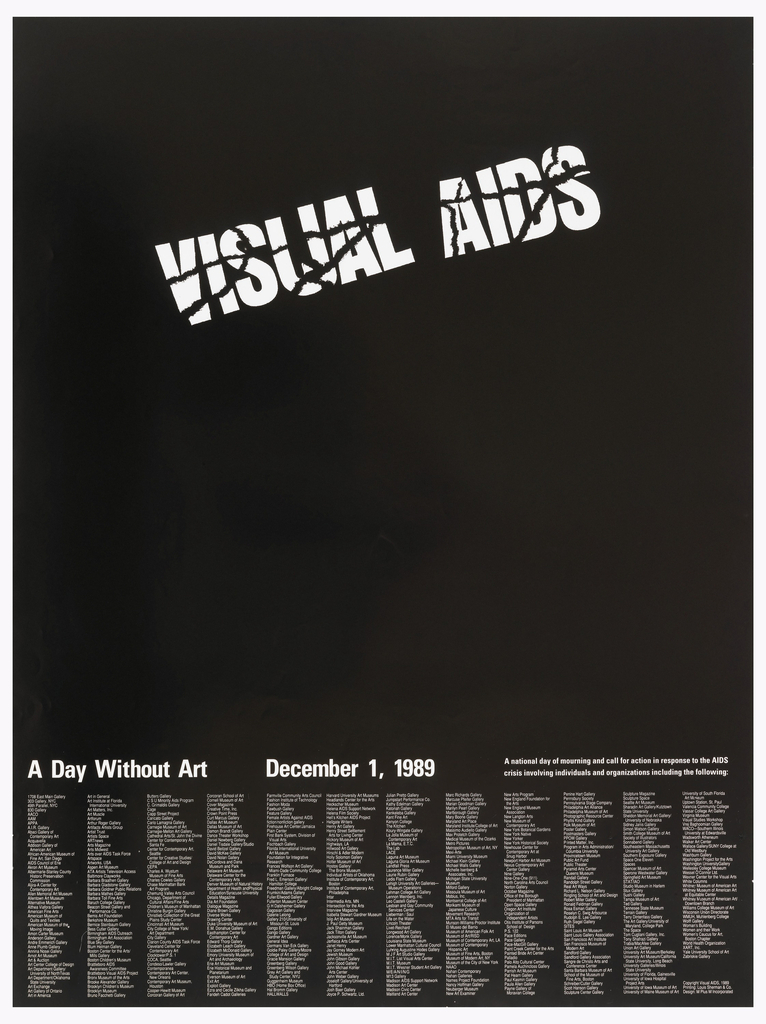

Founded in 1988, Visual AIDS honors and supports work produced by artists with HIV/AIDS and by the AIDS movement. The organization founded its Archive Project in 1994, which began as a research library and slide collection and became an online database. Hundreds of artists are represented, including Ellis. The organization also founded Day without Art, an annual observance held on December 1.

Poster, A Day Without Art, 1989; Designed by M Plus M Incorporated (New York, New York, USA) for Visual AIDS (New York, New York, USA); USA; offset lithograph on paper; 79.7 x 59.7 cm (31 3/8 x 23 1/2 in.); Gift of Visual AIDS; 1995-26-5

Cooper Hewitt’s collection includes several posters for Day without Art, including the poster that inaugurated this international day of mourning and action in 1989. Here, the absence of imagery speaks to the brutality of the epidemic. The poster honoring Ellis took a different direction by celebrating the achievements of a specific artist through his work, words, and biography.

Below is a discussion of Ellis’s paintings and photographs, written by art critic Ariel Goldberg for Art In America. This excerpt comes from a longer reflection on contemporary photography. Goldberg asserts the importance of Darrel Ellis in the history of queer photography.

Darrel Ellis was the star of “New Photography 8” in 1992 [MoMA exhibition] with mixed-media works distorting family photographs his father, Thomas, took in the 1950s in Harlem and the South Bronx. Ellis was a prolific artist who briefly worked as a security guard at MoMA in the late ’80s. He was also a black gay man who died of AIDS at the age of 34, just months before “New Photography 8” opened. While two Ellis works from the exhibition are in MoMA’s permanent collection, the portfolio provided on the website of the nonprofit Visual AIDS offers the most substantial body of his work online. A hand-drawn self-portrait of Ellis was frequently reproduced in the press to represent the controversial 1989 Artists Space exhibition “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” [curated by Nan Goldin]. A model for other photographers, Ellis wrote a haunting caption to his self-portrait for the Artists Space catalogue: “I struggle to resist the frozen images of myself taken by Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar.”

Ellis, who worked primarily in painting and drawing, used photography to document his practice. He eventually adopted a laborious process—employed in his final body of work for “New Photography 8”—that abstracted figurative representation by projecting his father’s negatives onto three-dimensional molds. Ellis then re-photographed the bent figures and scenes, sometimes adding geometric shapes to block and layer parts of the snapshots, and even further layered the new photograph with watercolor, gouache, pencil, and ink. Thomas Ellis’s pictures captured a family history that ruptured: he died at the hands of plainclothes police over a traffic dispute a month before Darrel was born. In the early years of appropriation, Ellis translated his father’s black-and-white snapshots into figurative drawings and paintings of a matching grayscale palette, as if to memorialize the parties and family milestones. Then came experiments with more turbulent renderings, such as an untitled image of a busy birthday party. Kids float around an adult who extends an arm outside the frame, perhaps serving food, his head reaching the streamers on the ceiling. A picture on the wall ripples like a flag in the wind. Ellis’s reworking of the birthday party scene collages embellishments and obfuscations that evoke the vicissitudes of memory and lost family bonds. Art historian Deborah Willis has described the work as conveying “the notion of absence . . . through excision or obstruction.” I rarely hear Ellis’s name uttered in discussion of queer photography, which should prompt us to question what is recognizable as “queer” in our rich histories.

— Ariel Goldberg for Art in America, 2018

Read more about Darrel Ellis at “In the Stacks with Lara Mimosa Montes: Darrel Ellis,” Coffee House Press in the Stacks, 2019.

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and the author of numerous publications, including Design Is Storytelling, The Senses: Design Beyond Vision, and How Posters Work.