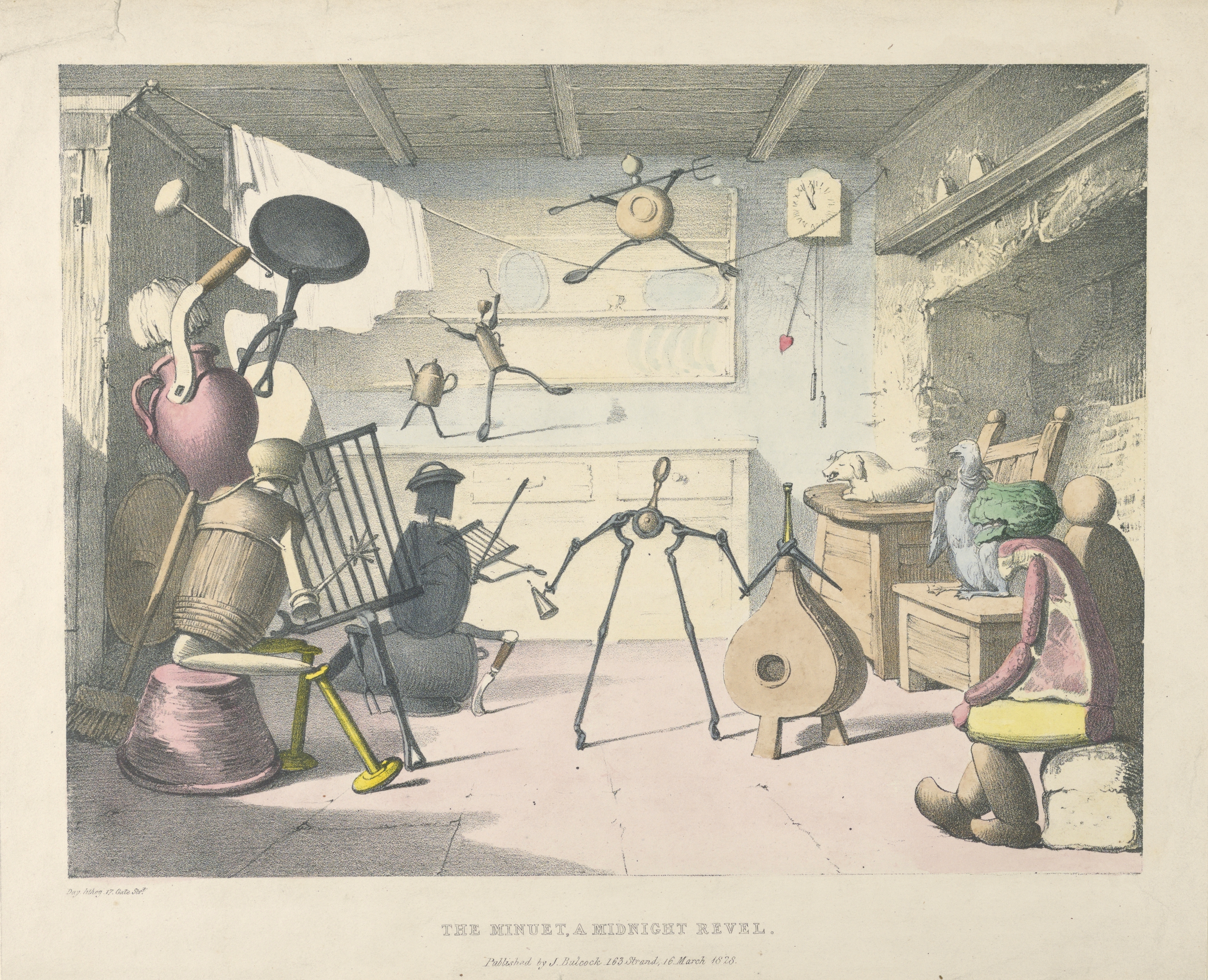

What goes on in the kitchen late at night? This whimsical print imagines the pantry come to life, as its normally inanimate occupants enjoy a jolly party. Dishes and cutlery dance to a merry tune played by a band of jugs, mops, pots and pans. A suckling pig, a goose, and a cabbage-headed meat-figure lend their voices to a chorus of tomorrow’s dinner.

Entitled “The Minuet, A Midnight Revel” and published in London in 1828, the print is the creation of William Day (British, 1797 – 1845), an early pioneer in the technique of lithography. Invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder (German, 1771 – 1834), lithography is a printing process that enables the transfer of designs to paper without the need to cut into wood or metal. Senefelder’s discovery made possible the rapid and economical production of prints using stone as the printing matrix. (The term “lithography” means “stone drawing.”) In early Victorian England, William Day realized that lithographs could be made even more cheaply by substituting zinc for stone. Together with his business partner Louis Haghe (Belgian, 1805 – 1886), Day became one of the most successful popular printmakers in England; in 1838 they were named “Lithographers to the Queen.”[1]

Day’s joyful image of kitchen revelry, although now relatively obscure, was once celebrated as a great achievement in British printmaking. In 1832, four years after its publication, the print was discussed at length in Jeffreys Taylor’s chronicle of recent inventions, A Month in London. Or, Some of its Modern Wonders Described.[2] In the book, Taylor’s protagonist, a “Mr. Finsbury,” takes delight in explaining to a group of naive young Americans how, thanks to the invention of lithography, this marvelous print could be produced at “the small cost of one shilling.”

Taylor’s description of “The Minuet, A Midnight Revel” is wonderfully evocative, and worth repeating here:

[The print] gave a view of an old kitchen, deserted, as usual at night, by its human inhabitants; but the bustle nevertheless was more than a little. The tongs, marching from the fireplace, were dancing a minuet with the bellows, which puffed themselves out for the occasion. The form of a musician was cleverly made up of a variety of culinary implements, holding a gridiron for a fiddle; whilst another performer, of similar materials, was thundering away at a frying-pan for a tambourine. A coffee-pot was capering away on the dresser, mounted on sugar-tongs as legs; whilst another vessel, whose limbs were composed of knives, forks, and skewers, footed it away on the tight rope above. The whole was innocently comical, and pleased the lads so much, that Mr. Finsbury promised to procure an impression for them.[3]

Dr. Julia Siemon is Assistant Curator of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

[1] For a history of lithography, see Antony Griffiths, Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques (University of California Press, 1996).

[2] Jeffreys Taylor, A Month in London; Or, Some of its Modern Wonders Described (London: Harvey and Darton, 1832).

[3] Ibid, 64 – 66.

One thought on “Up all Night with the Pots and Pans”

Reneau de Beauchamp on January 2, 2020 at 12:44 pm

Thanks ever so for sharing this delightful, pre-Disney, print with us! Beyond admiring the technical skills behind its production, it truly brings a smile to one’s face.