In celebration of May Day—at a moment when the essential role so many workers play in our community is at the forefront of our minds—we are re-posting a modified version of this blog by Virginia McBride originally published November 8, 2015. Formerly a 2014 Peter Krueger curatorial intern, then a Curatorial Assistant, and Cataoguer in Cooper Hewitt’s Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design, Virginia is now a Research Assistant in the Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Aim—pull—release! This archer draws back his bowstring and prepares to shoot. Peering into the distance, he points his arrow off the poster’s printed page. But the Dutch artist and designer Richard Roland Holst leaves no doubt about his target: a bullseye that hovers just above the archer’s head bearing the word “Livelihood” in Dutch. In this poster promoting the Labor Board (Raden van Arbeid), Roland Holst’s archer aims for a better life for working men and women. The fortifications of social security rise up around him in a stylized wall, labeled with benefits like “Widows’ and Orphans’ Funds” and “Old Age and Disability Pensions”—all protections provided by the Labor Board.

Roland Holst was a member of the Dutch Social Democratic Worker’s Party (SDAP), and the husband of a prominent socialist poet. His political views were shaped by the writings of William Morris, a British designer and activist for whom socialism carried the promise of artistic renewal. Describing Morris’ influence in her autobiography, Roland Holst’s wife Henriette wrote, “Capitalism had not only condemned the masses to a life of joyless toil, to ignorance and degeneration, it had also made the world ugly, murdered the beauty of nature as well as that of the old cities, and it had killed the spirit of community without which art cannot exist.”[1]

Her husband’s poster is a graphic throwback to better times. The medieval archer invokes a pre-industrial ideal when life was believed to be more communal.[2] But however grim Roland Holst’s view of the present, his challenge was to make worker’s rights relevant to the contemporary viewer. By placing his archer in a stylish frame of interlocking, geometric forms, he ushers him into the twentieth century. Like the archer’s arrow, Holst’s design points toward progress.

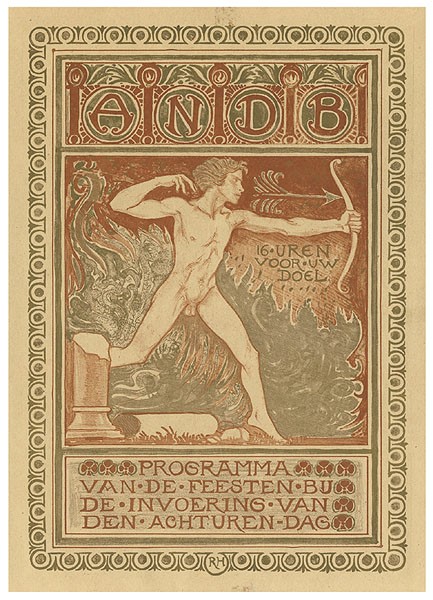

Richard Roland Holst, Cover for the General Dutch Diamond Workers’ Union (ANDB) “Program of Celebrations for the Introduction of the Eight-Hour Work Day (Programma van de feesten bij de invoering van de achturendag).” 1919.

This is one of several of Roland Holst’s designs to feature an archer. A similar marksman appeared on the designer’s pamphlet from the previous year, commemorating the 8-hour workday (see above). Though the archer lends these designs historical gravitas, he is only loosely affiliated with the worker’s cause, which was more often embodied by mechanics, engineers, and assembly-line laborers in contemporary poster designs. Roland Holst’s anachronistic choice reflects his wariness towards industrialization, which he felt abstracted work into mundane, repetitive, dehumanizing tasks. The archer’s poise, technique, and perfect aim embody a kind of skilled labor that Roland Holst saw slipping into the past. This nostalgia was aesthetic, as much as economic—Roland Holst scorned the abstract, geometric art of groups like the Dutch De Stijl on the grounds that their non-objective designs were themselves de-skilled. He saw their work as a consequence of capitalism and accused them of a “mechanization of the spirit.” [3]

[1] Johanna C. Prins, “Henriette Roland Holst-van der Schalk (1869-1952),” Caans-Acaen 11, no. 2 (Fall 1990): 43.

[2] Roland Holst was an important advocate in the Netherlands for community art (gemeenschapskunst)—a model of collective artistic creation that would bring together architects, artists, and designers to effect social change.

[3] Richard Roland Holst in his address to the Rijksacademie after assuming its directorship, 1918, quoted in Michael White, De Stijl and Dutch Modernism (New York: Manchester University Press, 2003): 88.

One thought on “A Designer Takes Aim”

Maria La Place on June 20, 2020 at 3:49 pm

I was really surprised to see that you never referred to “Holst’s poet wife” by her full name in the text, which, I can see by the footnote, is a hyphenated one that contains her birth name as well as her married name. This is an omission I almost never see these days, as it reduces women to appendages of their husbands. I hope you’ll correct this omission.