On September 23rd, 1758, an aspiring architect named Robert Mylne (1733 – 1811) wrote to his younger brother William (1734 – 1790) with astonishing news. At twenty-four years old, Robert had just become the first Briton awarded top prize in the Concorso Clementino, a famous architecture competition held every three years in Rome.[1] This drawing of an altar—completed during a timed exam—was submitted as part of his winning entry.

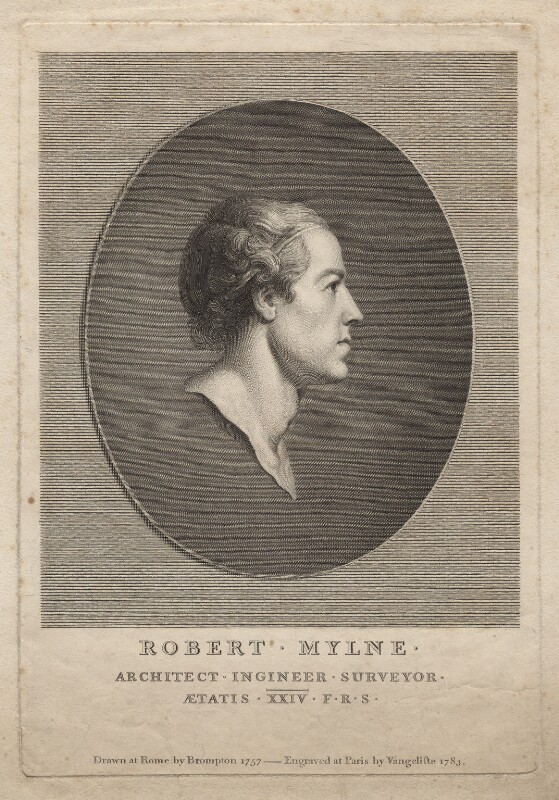

Portrait of Robert Mylne, 1783; engraved by Vincenzo Vangelisti after a drawing by Richard Brompton (1757); National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D5326

Robert and William Mylne were Scottish, born in Edinburgh to a family of builders: their ancestors were stonemasons.[2] After preliminary training in their native city, the brothers continued their architectural education in Europe. They traveled first to France, then made their way (mostly by foot, on account of the cost) to Rome, where they arrived in 1755.[3] In the Eternal City, Robert and William studied antiquities, attended lectures at the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of St. Luke), and built relationships with prominent architects such as Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778).[4] Unable to disguise their modest origins, in Rome the Mylne brothers earned the scorn of Robert Adam (1728 – 1792), a Scottish architect of much greater means. Adam described them as having “neither education nor money,” though he noted begrudgingly that Robert “begins to draw extremely well.” [5] In 1757, William returned to Edinburgh. Robert however remained in Rome, determined to try his hand at the Concorso Clementino.

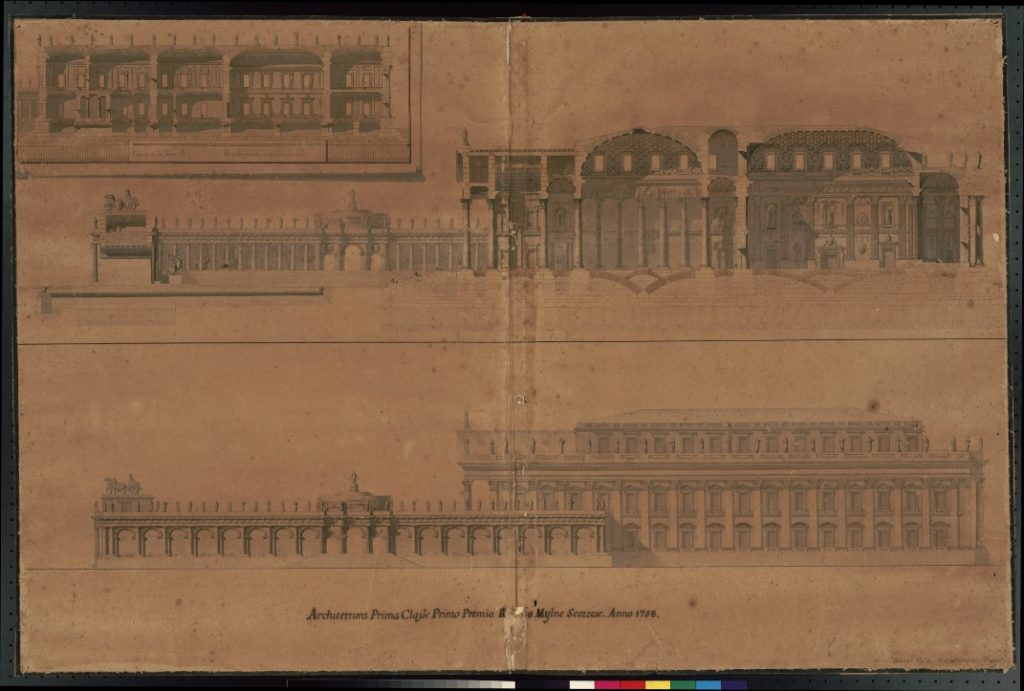

The contest, named in honor of Pope Clement XI, had been established by the Academy in 1702.[6] It carried enormous prestige, and was specifically intended for architects early in their careers. The competition consisted of two separate trials. First, several months before each Concorso, the Academy would announce the subject for the upcoming contest. In Robert Mylne’s year, the contestants were tasked with producing a series of drawings for “A Public Building with a Memorial Gallery to exhibit Busts of Eminent Men.”[7] When the deadline arrived, competitors submitted plans, sections, elevations, and whatever other drawings they felt would convince the judges of the superiority of their projects.

Robert Mylne, Interior and Exterior Longitudinal Sections, Concorso Clementino, 1758; Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca. (The yellow color of this drawing is the result of extended exposure to light during display.)

In the second phase of the contest, the architects gathered for an extemporaneous feat of drawing, the subject kept secret until the event. Mylne sat for this test, called a prova, on the 7th of September, 1758.[8] Afterwards, he recalled the experience in the letter to his brother: sitting before a panel of judges, the competitors were given two hours to design a “magnificent” altar adorned with composite columns.[9] “I am sure you are quaking for me now,” Mylne wrote, “however I made it out and a fine one—in comparison with the rest.”[10] What he produced was this relatively simple sheet in the Cooper Hewitt collection, bearing the elevation and plan of an altar in a modern, French-inflected Neoclassical style. At the top, the architect has added and identified allegorical figures of Hope, Humility, and Faith. A few days after the prova, Mylne learned he had been unanimously selected for the first prize. The announcement shocked him. “I think on my heart when I received the news—thump, thump, thump, I feel it yet…”[11]

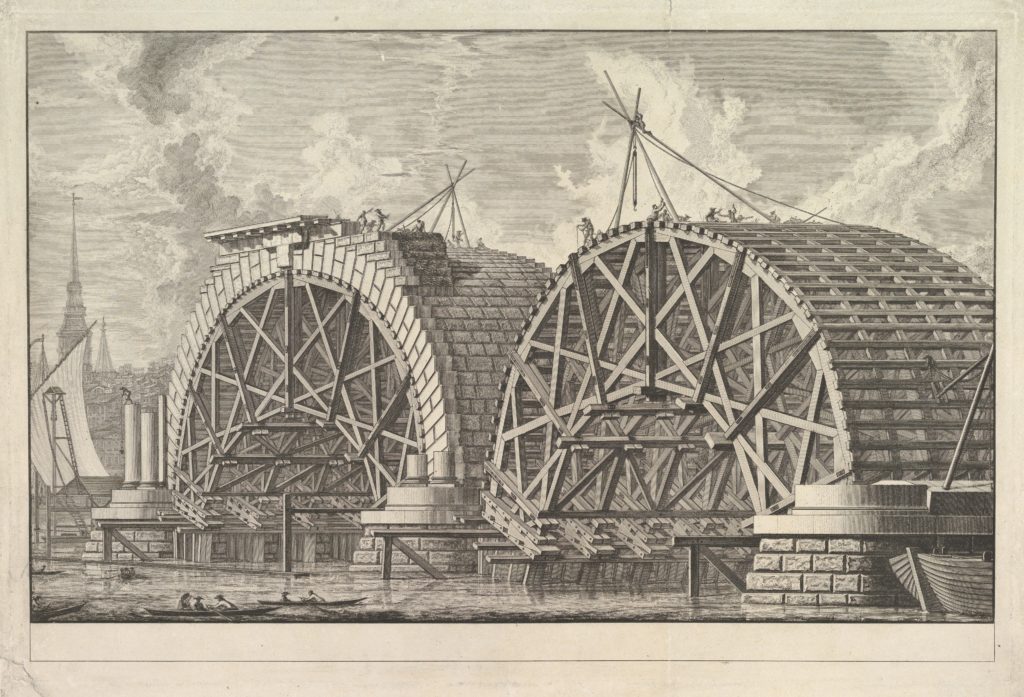

His triumph in the Concorso Clementino launched Mylne’s career. In Rome he was honored with a fabulous ceremony attended by Cardinals, and presented with a silver medal. His winning drawings were displayed in the Academy building and earned much praise (although not from Robert Adam and his supporters, who—full of sour grapes—continued to sneer). [12] Mylne returned to Britain the following year, where his Italian victory was soon overshadowed by another major success. In 1760 he submitted drawings for a competition to design the new bridge over the Thames at Blackfriars. And won. [13]

A View of Part of the Intended Bridge at Blackfriars, London, ca. 1764; etched by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; Metropolitan Museum of Art, 62.600.683

Dr. Julia Siemon is Assistant Curator of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

[1] Damie Stillman, “British Architects and Italian Architectural Competitions, 1758 – 1780,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol.32, No. 1 (Mar., 1973): 44 – 66, 44 – 45

[2] A. E. Richardson, Robert Mylne: Architect and Engineer, 1733 to 1811 (London: B.T. Batsford, 1955), 15

[3] William first went to France on his own, where he studied for a period before being joined by Robert so that the brothers could travel together to Italy. Stana Nendacic, “Architect-Builders in London and Edinburgh, c. 1750 – 1800, and the Market for Expertise,” The Historical Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3 (September 2012): 596 – 617, 599

[4] Richardson, 14

[5] Lindsay Stainton, “Hayward’s List: British Visitors to Rome, 1753 – 1775,” The Volume of the Walpole Society, Vol. 49 (1983): 3 – 36, 28; Nenacic, 611

[6] Stillman, 44

[7] Stainton, 28. The rules of the competition listed several specific requirements, including architectural elements such as an atrium, a theater, etc., as well as clarifications regarding the submission of a “plan, prospect, and section, and anything else that might be required to give a good demonstration of the idea.” These were printed in a celebratory publication for the awards ceremony, Delle lodi delle bele arti… del concorso celebrate dall’insigne Accademia del Disigno di S. Luca… l’anno MDCCLVII (Rome, 1758).

[8] Stillman, ibid. The Cooper Hewitt collection also includes a prova carried out by another British architect, Joseph Gandy, who won the Concorso Clementino in 1795.

[9] “Magnifico Altare con colonne d’Ordine composito per farsi in una della principali Capelle con suoi ornati.” See Stillman, 45

[10] Robert Mylne to William Mylne, 23 September, 1758, in Stillman, 44.

[11] Mylne in Stillman, ibid.

[12] Stillman, 41 n. 21.; 44

[13] For the bridge, see Roger Woodley, “‘A Very Mortifying Situation’: Robert Mylne’s Struggled to Get Paid for Blackfriars Bridge,” Architectural History, Vol. 43 (2000): 172 – 186

One thought on “A Surprise Victory for Robert Mylne”

Reneau de Beauchamp on July 6, 2020 at 12:03 pm

Thank you SO VERY MUCH for submitting this intriguing report! Now – if only you had included a view of the completed Blackfriars Bridge ;->