In 2021, the Smithsonian Institution celebrates 175 years since its founding. On October 7, 1976, Cooper Hewitt opened, joining the Smithsonian and becoming the nation’s design museum. Learn how that came to be.

The following has been adapted from Life of a Mansion: The Story of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum by Heather Ewing, available for purchase through SHOP Cooper Hewitt.

THE CREATION OF COOPER HEWITT

In 1963, the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art announced that it was disbanding its museum. Inventor and industrialist Peter Cooper, who believed that education lay at the heart of a healthy civic state, had established the school in 1859 to provide an institution of higher learning “open and free to all.” Central to that mission had been the creation of a museum, which was accomplished through the efforts of his granddaughters, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, in 1897. For more than half a century, inspired by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the museum amassed and organized its vast reference collections in ways conducive to exploration of, comparison of, and ongoing dialogue on decorative arts and design.

The looming dispersal of the Cooper Union Museum generated a tremendous outcry. Philanthropist Alice Kaplan, then president of the American Federation of Arts, established the Committee to Save the Cooper Union Museum in the living room of her Upper East Side town house—a committee, as she described it, that “was formed in outrage.” Henry Francis du Pont, scion of the chemical company family, who had turned his Delaware estate Winterthur into one of the premier American decorative arts museums, served as chairman, despite being nearly 90. Within a few months the group numbered more than 250 people.

As the critic Ada Louise Huxtable so aptly described it, “The museum was disowned and faced with dismemberment by a financially hard-pressed Cooper Union, whose architecture students were more involved with urban problems than ormolu.” She called the situation a “cultural cliff-hanger.” For a while, it seemed likely that the collection would be dispersed, sold at auction, or taken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art—a solution that would have sent much of the collection into storage, never to be seen. Over four years the beleaguered curatorial staff of the museum and the committee to save the museum worked to preserve the collection intact and find a new home. Du Pont facilitated the development of a relationship with the Smithsonian. With an endorsement from the American Association of Museums, the Smithsonian agreed in 1967 to make the newly named Cooper-Hewitt Museum part of the national collections.

Carnegie Corporation of New York came forward with the offer of a home for this new entity: the Carnegie Mansion, which was being vacated by the Columbia University School of Social Work in 1969. Initially the foundation leased the building to the Smithsonian for $1 a year, with an option to purchase. When it proved difficult for the museum to fundraise for what seemed with the lease to be a temporary solution, the foundation decided instead in 1972 to give the house—then valued at about $8 million—outright.

The Carnegie Mansion at 2 East 91st Street in New York.

For the Smithsonian, it was an adventure. Cooper Hewitt represented the institution’s first museum outside of Washington, D.C. It also soon became the first Smithsonian museum to be led by a woman. In 1969, Secretary of the Smithsonian S. Dillon Ripley appointed Lisa Taylor as director; until that time she had been in charge of the Smithsonian Associates, a new organization dedicated to building public programming for the institution. When she arrived in New York, she was the only female director of a museum in the city.

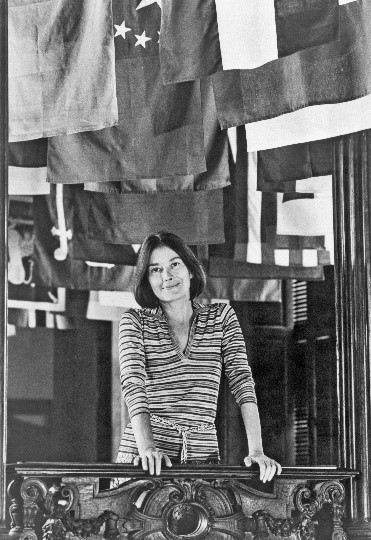

Lisa Taylor on the grand staircase of the Carnegie Mansion in 1976, with a display of flags from the inaugural exhibition MAN transFORMs.

COOPER HEWITT OPENS TO THE PUBLIC

The museum opened in 1976, America’s bicentennial year, on October 7, with tremendous fanfare. Around the city, other museums hosted Salutes to the New Museum, small satellite exhibitions of loans from Cooper-Hewitt that interacted with their own collections: drawings at the Morgan Library, rare natural history books at the American Museum of Natural History, painters’ sketchbooks at the Whitney, and more.

The opening exhibition at the Carnegie Mansion was not a selection of highlights from the permanent collection, but instead what director Lisa Taylor billed “a very shocking show,” entitled MAN transFORMs. The museum invited Austrian artist-architect Hans Hollein to curate the show, which featured contributions from international designers such as Buckminster Fuller, Richard Meier, George Nelson, Ettore Sottsass, Arata Isozaki, and others. MAN transFORMs emphasized the role that design has played in human history, affecting even the most elemental and basic aspects of our lives. Every space over three floors of the mansion was treated like an installation. One room featured an array of birdcages from varied periods and locales; another room displayed an enormous table filled with different kinds of breads made all over the world. “The objective,” according to Hollein, “was to produce a series of encounters that would unfetter the imagination.”

Tetrahedrons and octahedrons in Carnegie’s library served as an entry to Buckminster Fuller’s film exploring the “elegantly meshed design of the universe,” part of MAN transFORMs (October 7, 1976–February 7, 1977). Courtesy of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

Taylor brought a playful, energetic program to the mansion. Nothing was off-limits, recalled former curator of exhibitions Dorothy Twining Globus: “shopping bags, lace, ocean liners, writing and reading, soup tureens and mustard pots, Antoni Gaudí, Robert Adam, the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, Mad King Ludwig,” and more. The public came to expect the unexpected.

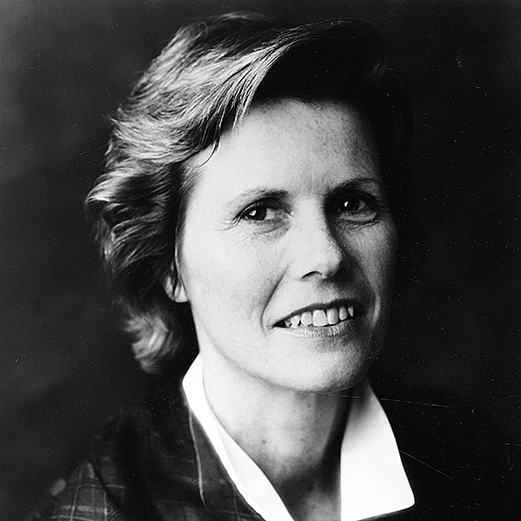

Taylor retired in 1987 and was followed by Dianne Pilgrim, then chair of the Decorative Arts Department at the Brooklyn Museum. Pilgrim led the museum for more than a decade, during which time she focused on making the collection more accessible, both conceptually, in terms of broadening what fell under the definition of design, and physically, in transforming the mansion campus.

Dianne Pilgrim.