Written by Sarah D. Coffin and David A. Hanks

Adapted from Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism, edited by David A. Hanks, published in May 2021 by Yale University Press in association with the Richard H. Driehaus Museum. Republished by permission of Yale University Press. Purchase it at SHOP Cooper Hewitt.

The work of French architect Hector Guimard (1867–1942) has come to define art nouveau in the popular imagination. Introduced to an international audience at the 1900 Exposition universelle in Paris, the art nouveau style represented a radical break from the classical and revival styles of the nineteenth century in its embrace of naturalistic forms and its unity of architectural, decorative, and fine arts. Perhaps the most famous extant exemplars of art nouveau are Guimard’s station designs for the Paris subway, or Métropolitain: built between 1900 and 1912, these are considered so emblematic of the style that French art nouveau was sometimes referred to as “Le Style Métro.” While the popularity of art nouveau has waxed and waned since its introduction, architectural historians and critics now recognize the fundamental modernity of Guimard’s work. Underlying the sinuous curves and often exuberant ornament of his buildings and furnishings is a rejection of classicism in favor of a nature-based aesthetic, a use of industrial technologies, and a unified design of architecture and the arts. Guimard also focused on making modern design affordable, accessible, and a force for social good—an approach that aligned his work with concurrent modern movements in Europe and America.

Métro Entrance Medallion, circa 1900; Designed by Hector Guimard (French, 1867–1942); Produced by Val d’Osne Foundry (Saint-Dizier, France); Cast iron, enamel; 73.7 × 61 cm (29 × 24 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Harry C. Sigman, 2013-21-6

Details about Guimard’s personal life are sparse, and very little personal correspondence survives to provide biographical information or insights.[1] He was born on March 10, 1867, in Lyon, France, the son of an orthopedist and a linen maid and the middle of three children. In 1883, the Guimard family moved to Paris, where Hector was already at school. His studies focused on classic Beaux-Arts training. Accepted to the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris in 1882, when he was fifteen, Guimard was a talented and ambitious student.[2] Within his first six months he advanced to the second year, and he entered the architecture department in December 1883, going on to win a number of student medals, including the school’s grand prize for architecture, the Prix Jaÿ, in 1885. In 1888, while still in school, and without an apprenticeship or any experience with an established firm, Guimard began working as an architect. While his architectural practice developed between 1891 and 1900, Guimard taught drawing for the girls’ section at the École des arts décoratifs.

Guimard’s interest in modern design was augmented by a group of precursors who adhered to a common theme: design reform based on nature rather than the copying of past styles. Function and materials dictated form, and industrial production was embraced. Among Guimard’s most significant design influences were French architect and theorist Viollet-le-Duc; the British Arts and Crafts movement, which flourished between 1880 and 1920; and Belgian architect Victor Horta (1861–1947). Although Guimard found the Beaux-Arts tradition essential in architectural education, he diverged from its general emphasis on grand and ornate classicism in favor of an abstract modern style based on natural forms, which he judged appropriate for the Industrial Age. In so doing, he showed the significance of Viollet-le-Duc’s teachings, which advocated the Gothic style with its simplified forms as a way to reform design. Viollet-le-Duc proposed using modern building materials, such as cast iron, and rationalist methods of construction. In his Entretiens sur l’architecture (Discourses on Architecture), a series of essays dedicated to Gothic architecture published in 1863–72, he concentrated in particular on the use of iron and other new materials and on the importance of designing buildings adapted to their function rather than reproducing older styles.

Another significant influence on Guimard’s work was the British Arts and Crafts movement; in fact, Guimard’s interests were more aligned with the British philosopher-designers than with his French compatriots. Contemporaneous with art nouveau, the Arts and Crafts movement also shared the objective of reforming design. As Georges Vigne observed, “Great Britain was a much more obvious place for an architect to encounter modernity than the Continent, because in Britain the decorative arts had long been intimately associated with architecture.”[3] This unified approach is manifested in the work and writings of William Morris, John Ruskin, and A. W. N. Pugin. With a travel grant he received in 1895 from the Ministry of Public Education and the École des Beaux-Arts, Guimard visited Great Britain and Belgium, followed by a separate trip to the Netherlands and Belgium. At that time, his work already showed a familiarity with and affinity for British Arts and Crafts design: the Hôtel Jassedé of 1893 exemplified a revival of traditional crafts in its ceramic decoration and its garden setting, and the sketches from his visit to Great Britain reflected the growing appeal of the Arts and Crafts cottage style and perhaps a diminished interest in the work of Viollet-le-Duc.[4]

Another of Guimard’s most profound influences was his contemporary, architect Victor Horta, who introduced Guimard to the newly developing art nouveau style. On his second study trip in the summer of 1895, courtesy of the travel grant he had received, Guimard visited Horta’s recently completed Hôtel Tassel, a townhouse designed in this style, in Brussels and met the architect himself.[5] This introduction to Horta was a transformative experience for Guimard and an inspiration for his own work, clearly seen in Castel Béranger.[6] Guimard’s letters to Horta expressed great admiration for his work: “In you I have met the architect truly worthy of the name.”[7] Before this trip, Guimard’s architecture was more Gothic and less organic in appearance. Afterward, the curves of art nouveau began to appear in his work, notably in changes to the interior of Castel Béranger. Guimard did not copy the older architect’s work as much as he derived inspiration that allowed him to pursue a new, individualized visual language. A comparison of the interiors of Hôtel Tassel and Castel Béranger shows that ornamental forms and motifs are similar; the primary difference was the choice of materials, cast iron in Guimard’s project, exotic woods in Horta’s.

In a 1902 article introducing the art nouveau style for the Architectural Record, an American architectural magazine, Guimard wrote, “Nature is a big book from which we can draw inspiration, and it is in that book that we must look for principles, which, when found, have to be defined and applied by the human mind according to human needs.”[8] Among these principles, Guimard explained, are logic, which considers all conditions and factors in a project; harmony, which unifies exteriors, interiors, and surroundings; and sentiment, which “leads by emotion to the highest expression of the art.”[9] At the time Guimard was exploring art nouveau, it was flourishing throughout Europe, under different names in different countries. Although specific attributes varied from one interpretation to the next, all were characterized by a rejection of historicism, a unity of design elements, and a focus on nature as formal inspiration. Like Dresser, Guimard wished to make his design aesthetic available, via mass production, to a broad social spectrum—“to put the beautiful within reach of everyone.”[10] This attitude was a motivation throughout his career.

Guimard’s abstract art nouveau designs, often composed of curves and whiplash decorations, were based on natural forms that evoked movement and growth, expressed in novel ways. His work was distinctive in its combination of multiple materials, including cast and wrought iron, lava, concrete, ceramic, multiple colors of brick, and numerous types of stone, such as buhrstone and sandstone. He used these to create surprising forms—for instance, bizarre vegetal and floral forms, or the impression of his own hand for bronze doorknobs. His furniture designs evolved from the dark mahogany of Castel Béranger to lighter pearwood, which he favored because of its color and grain. Large openings in the asymmetrical, fluid forms of Castel Béranger furniture contrast to the predominantly symmetrical, tight compositions of the pieces for his own house.

Right: Side Chair from Hôtel Guimard, circa 1912; Designed by Hector Guimard (French, 1867–1942); Produced by Ateliers d’Art et de Fabrication Guimard (Paris, France); Pearwood, leather, brass; 113.5 × 46 × 48 cm (44 11/16 × 18 1/8 × 18 7/8 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Mme Hector Guimard, 1948-114-1. Left: Door Handle, 1900; Designed by Hector Guimard (French, 1867–1942); Bronze, gold; 8.9 × 10.2 × 10.2 cm (3 1/2 in. × 4 in. × 4 in.); The Collection of Richard H. Driehaus, Chicago, 20168

Dining Room in Hôtel Guimard, Paris, France, circa 1913; Unidentified photographer; Gelatin-silver print, toned; 21.6 × 28.1 cm (8 1/2 × 11 1/16 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Mme Hector Guimard, 1956-78-11

Guimard’s early projects were for a relatively small group of loyal clients, most newly rich, living in his neighborhood of Auteuil. His floor plans are distinctive, often carefully worked out to suit awkwardly angled lots. He used mass-production technology, such as standardized building components in cast iron, to promote his vision of modern design for all. At the same time, for some of his commissions, particularly for wealthier and more adventurous clients, he began to introduce interior furnishings. After marrying Adeline Oppenheim (1872–1965), an American artist from a wealthy Jewish banking family in New York, in 1909, Guimard designed Hôtel Guimard, a new house on avenue Mozart, along with the interiors, furnishings, carpeting, draperies, and even table linens. Except for their World War I–era sojourn, during which they stayed at Hôtel Gassion in Pau, the Guimards lived in Hôtel Guimard from 1913 to 1930; they then moved to the fourth floor of an apartment building at 18, rue Henri-Heine, which Guimard had designed in 1921 and completed in 1926, in an area he hoped to develop.

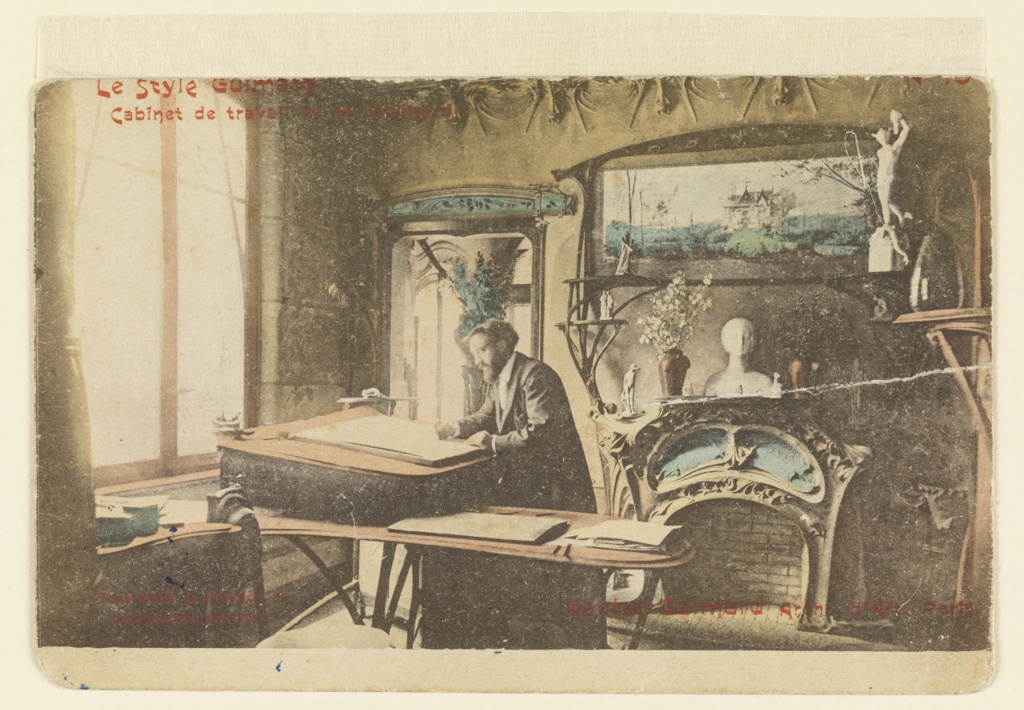

Guimard was as advanced in the ways he promoted his work as he was in the work itself. In 1900, he branded himself “architecte d’art” to distinguish his creative ambitions from purely commercial architecture; that same year, he first used the motto “le style Guimard.” In 1903, he used both phrases in a collection of twenty-four postcards printed to promote his designs. He seems to have abandoned architecte d’art shortly afterward, but he continued to use le style Guimard until it was succeeded by “le style moderne” around 1910, because he wanted to be associated with the notion of modernity throughout his career. In her communications to museums receiving gifts of Guimard’s designs, Mme Guimard repeatedly reinforced the importance of le style Guimard brand.

Postcard No. 10 from Le Style Guimard series, “Hector Guimard in His Workroom at Castel Béranger,” 1903; Black ink, brush, watercolor on sepia paper; 8.9 × 13.9 cm (3 1/2 × 5 1/2 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Madame Pejol, 1958-84-1

In September 1938, the Guimards left Paris, which they both loved, anticipating the approaching war.[11] A Nazi-occupied France would be a threat to Adeline Guimard because of her Jewish heritage and to Hector Guimard because of his liberal political activism. Indeed, less than two years later, in May 1940, the Germans attacked France and, within weeks, defeated the French army and established a de facto Nazi dictatorship that would last more than four years. Before Guimard left France, he corresponded with Alfred H. Barr Jr., founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who made annual pilgrimages to Europe to see new art and architecture firsthand and to meet artists in preparation for exhibitions at the museum. The two may have met in Europe before the Guimards’ move.[12] In March 1936, Guimard wrote to Barr regarding MoMA’s upcoming exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, which included the architect’s work.[13] Perhaps already thinking of his legacy, Guimard described his artistic production, which he divided into four periods: 1900, “Search for a New Style”; 1910, “Realization of this Style”; 1920, “Evolution of the style due to the elimination of any work requiring artists”; and 1930, “Museum Proposals, where in the reinforced concrete structure, the formwork is preserved, representing a new architectural concept.”[14] Barr identified the essential aesthetic significance of Guimard’s work and his influence on modern artists: “Guimard has created a new type of biomorphic abstract form. It is a symbolic form that expresses the original rhythms of nature. . . . This is why Guimard’s highly simplified and dynamic forms have aroused the admiration not only of surrealist painters but also of Arp and Brancusi, Matisse and Picasso, and even of abstract expressionists! Guimard, Horta, Van de Velde and others gave abstract biomorphic art a formal language one generation before the painters. Guimard had a very special influence because his work was easily accessible. From the twenties to the fifties, all abstract artists look at Guimard’s symbolism. As Picasso said, ‘Guimard was everywhere.’”[15] Due in part to an exhibition proposal by Barr in 1933, appreciation of art nouveau and recognition of Guimard’s work in America began even before his move to the United States. Although Barr’s exhibition was not approved, in June 1949 MoMA exhibited art nouveau acquisitions in a special gallery, including work by Guimard, much of which was part of Adeline Guimard’s 1949 gift to the museum after her husband’s death.[16]

Hector Guimard died on May 20, 1942, at the Adams Hotel on 86th Street near Fifth Avenue, the Guimards’ New York residence. In poor health, he had not been able to work after the move to the United States.[17] A photo of Guimard at a sanatorium in Greenwich, Connecticut, shows an elegantly dressed gentleman seated in the garden with a group. The popularity of his work, which rose and fell throughout his life and after his death, was at its height in the first decade of the twentieth century, following the design of the Paris Métro. Although he continued to design buildings through the 1920s—including visitors’ quarters for the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs (World’s Fair) in Paris and interiors for his rue Henri-Heine apartment building—le style Guimard began to fade with the rise of Art Deco and the International Style. The short-lived art nouveau was on the wane by 1910, long before Guimard moved to New York.

Following her husband’s death, Mme Guimard devoted herself to preserving his legacy, making important donations to American and French museums, though she did fail to convince anyone in France to set up a Guimard museum in Hôtel Guimard. Her attempt to persuade newspapers to recognize Guimard’s career at the time of his death was unsuccessful, even with the help of their friend and advocate Alfred Barr Jr.[18] Happily, Adeline lived long enough to see a revival of interest in art nouveau and her husband’s work: in 1960, five years before she died, the Museum of Modern Art opened the exhibition Art Nouveau. More exhibitions would follow: a monographic show at MoMA in 1970 and a major retrospective at the Musée d’Orsay in 1992. Each of these presentations has taken a step toward a deeper and broader understanding of Guimard’s importance in the history of modern design; yet there is much still to be discovered in the work of this architecte d’art.

Sarah D. Coffin was Curator and Head of Product Design and Decorative Arts at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum from 2004 to 2018.

David A. Hanks is Curator of the Liliane and David M. Stewart Program for Modern Design.

The exhibition Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves is on display at Cooper Hewitt through May 21, 2023.

Notes

[1] A chronology of Hector Guimard’s life appears on the website of le Cercle Guimard, www.lecercleguimard.fr/en/biography/.

[2] A detailed summary of his education can be found in Georges Vigne, Hector Guimard: Architect, Designer, 1867–1942 (New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2003), 21–25. See also le Cercle Guimard’s chronology.

[3] Vigne, Hector Guimard, 14.

[4] Although there is no known itinerary for this trip, Guimard’s drawings at the Musée des arts décoratifs include watercolors for houses on the Isle of Wight and in Sussex. According to Claude Frontisi, Guimard visited Arthur L. Liberty (who sold Dresser’s glass and textiles), Aubrey Beardsley, Edward Godwin, and Christopher Dresser himself. Claude Frontisi, “Hector Guimard en son temps,” in Thiébaut et al., Guimard (exh. cat.), 31.

[5] Guimard arranged an exhibition of sketches of Horta’s work in Paris at the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts; it opened on April 25, 1896. Among the projects shown were architectural sketches Guimard made in England, Scotland, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Vigne, Hector Guimard, 60–61, 100. He also dedicated his portfolio, Le Castel Béranger, published in 1898, to Horta.

[6] As Philippe Thiébaut notes in his essay in this publication, “The First Gesture.”

[7] Hector Guimard to Victor Horta, May 8, 1896, reproduced and translated in Brunhammer et al., Art Nouveau, 410.

[8] Hector Guimard, “An Architect’s Opinion of ‘l’Art Nouveau,’” Architectural Record 12, no. 2 (June 1902): 127.

[9] Guimard, “Architect’s Opinion,” 127–31.

[10] Hector Guimard to Fernand Hauser (probably), December 11, 1913, cited in Vigne, Hector Guimard, 340.

[11] The Guimards traveled from Le Havre, France, to New York on the SS Normandie, September 7–12, 1938. According to the passenger records from that voyage, Hector had visited New York in 1912. The Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, passenger search, accessed September 3, 2019.

[12] Alfred H. Barr Jr. to Adeline Guimard, June 6, 1945, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard papers. Barr wrote to Adeline that he remembered her husband with admiration and affection.

[13] The Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 9, 1936–January 17, 1937. Guimard’s loans included drawings and photographs of the Métro entrances and Hôtel Guimard, as well as color plates from Le Castel Béranger.

[14] Hector Guimard to Alfred H. Barr Jr., March 10, 1936, MoMA Exhs. 55.4, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. An English translation of this letter appears in Vigne, Hector Guimard, 378.

[15] F. Lanier Graham, “Guimard, Viollet-le-Duc et le modernism,” in Guimard: Colloque international, Musée d’Orsay, 12 et 13 Juin 1992 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 18–19.

[16] Philip Johnson to Adeline Guimard, March 30, 1949, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard papers, discusses gifts he wants for the exhibition.

[17] Auguste Bluysen to Adeline Guimard, October 7, 1947, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard papers, Mss Col 1264; cited in Bruno Montemat, “Les cercles artistiques, littéraires et philosophiques d’Hector Guimard, ‘architecte d’Art,’” Romantisme 177 (March 2017): 107.

[18] Alfred H. Barr Jr. to Adeline Guimard, May 21, 1942. Barr agreed that “the press did not accord [Guimard] the attention his distinguished career deserved.” He telephoned the arts editor for the New York Times in an apparently futile attempt to get something published. Adeline Oppenheim Guimard papers.