Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

For a few years I’ve been corresponding via email with Pam Holaday, who fortuitously replied to a postcard sent to her by my colleagues Wibo Bakker and K. J. Hepworth, who were trying to track down members of the original team who had worked on Henry Dreyfuss’s 1972 publication Symbol Sourcebook. Pam and I exchanged photographs of our lives in Pasadena, California, and Lewes, East Sussex, United Kingdom, respectively. Pam shared many memories of her experiences working on this iconic book from June 1970 to late 1971. It had a profound effect on her life that is still fresh in her memory 50 years on. In March 2022 we finally got to meet, and she welcomed me into her home in a leafy district of Pasadena, where she introduced me to her friends and neighbors and her dog Mattie.

We talked about her work, her life, and her family. I recorded her words, and this writing is based on a transcript of the conversation we had, which I found very moving. It brought to life how Henry managed to bring such an ambitious symbol project to fruition in such a relatively short time. It was a huge privilege to meet Pam and we have become long distance friends across the pond. The most astonishing thing I found out from Pam is that she drew the majority of the symbols in the Symbol Sourcebook by hand, and there are over 3,000—a monumental feat!

Pam was raised in Pasadena and came from a family with a solid professional background with German origins. Her father was a successful engineer and attorney who at one point in his career worked with Hopi and Navaho Native Americans. Her mother rose to be a top secretary for Jet Propulsion Lab at Caltech in Pasadena, and her brother fought in Vietnam. Pam gained a bachelor of science degree from University of California, Davis, and before working on the Symbol Sourcebook she worked in a microbiology lab. She had no formal experience in art and design when she began working on the Symbol Sourcebook project on June 22, 1970, starting the day after her interview. She was 26. This job was not what Pam’s parents expected her to do with her background in science, and her family would not have understood the fact that her new role would involve hand-drawing symbols all day (often including the weekends) for the next 18 months.

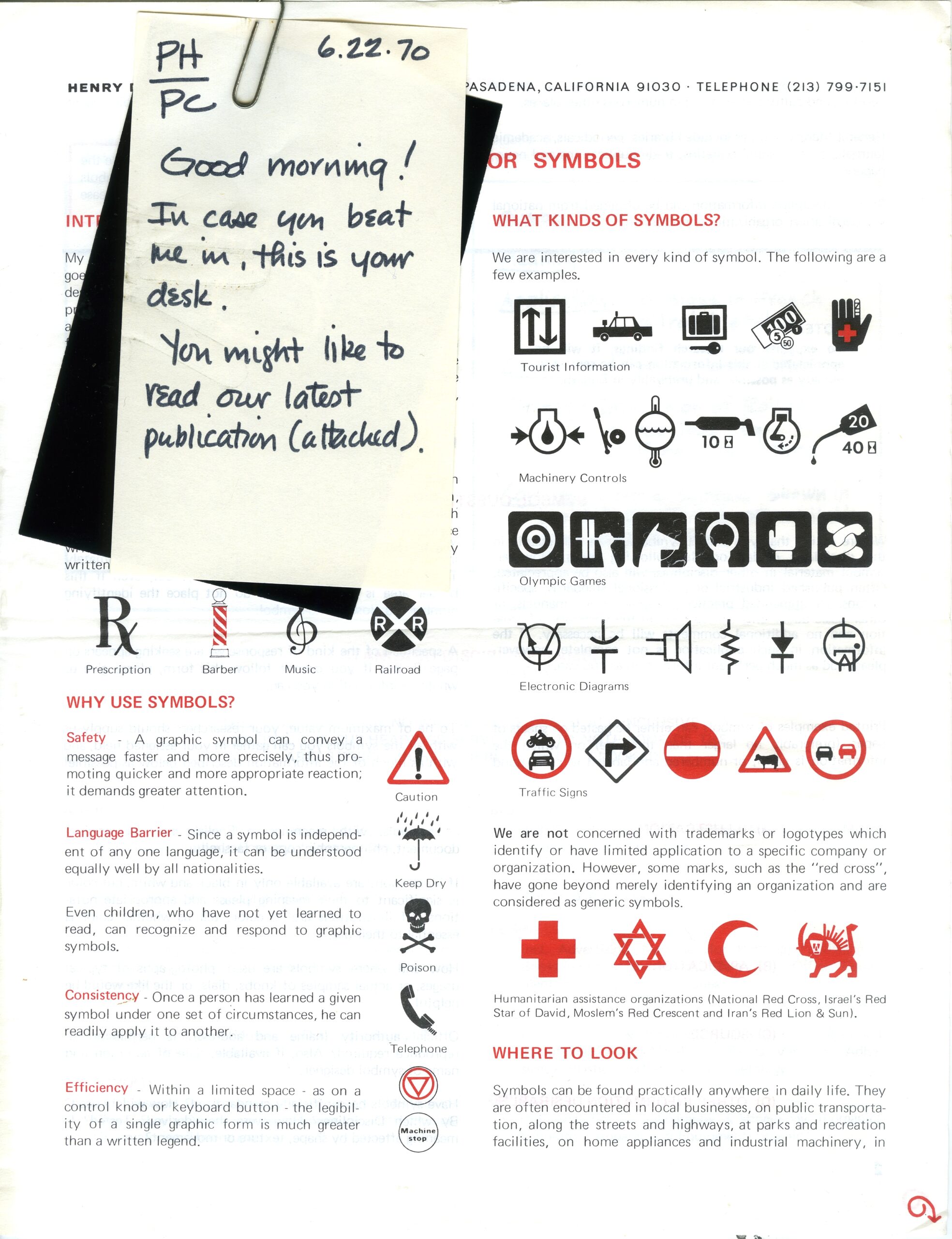

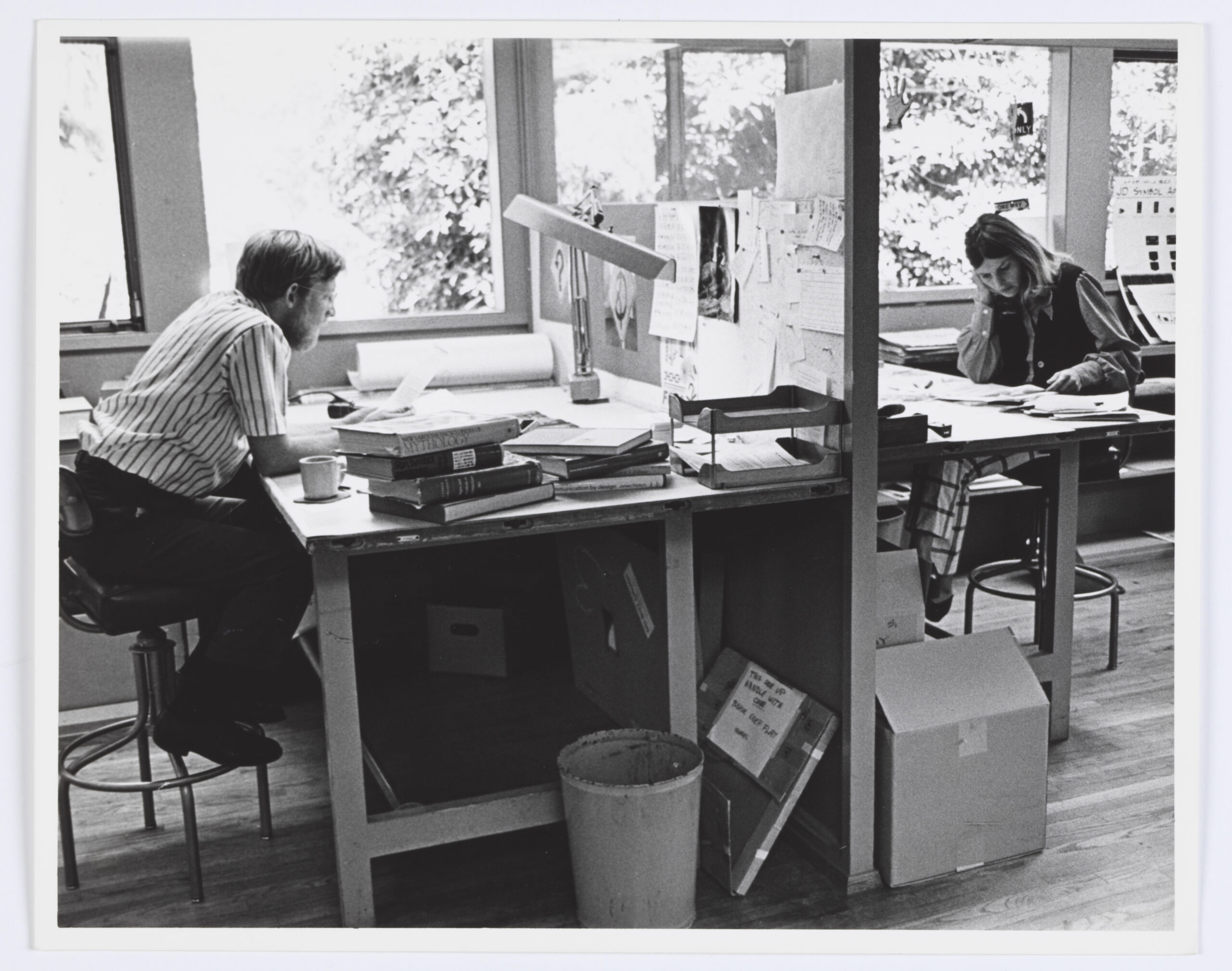

Pam was hired after seeing an advertisement at Pasadena City College. Henry was always pushing for younger people to work in his studios, so he found this a good place to recruit energetic young people who would stimulate activity in the working environment and not demand high salaries. Pam found the pay to be adequate, and she could afford her own apartment and car. On her first day, she found a welcoming note from Paul Clifton, the project manager, on her desk, along with a hobo symbol of a cat, which means “kind lady lives here” (fig. 1). She describes arriving in the spacious studio, which was full of rows of large flat drafting tables standing upright—the remnants of Henry’s thriving Pasadena industrial design practice (fig. 2). Henry had no formal involvement with Henry Dreyfuss Associates (they dropped the ampersand to form the new company) after 1969; the company moved to New York and was headed by Donald Genaro, its president until 1994.

Figure 1: Note, Paul Clifton to Pamela Holaday, June 22, 1970; Courtesy of Pamela Holaday

Figure 2: George Ball and Pamela Holaday, Office of Henry Dreyfuss, South Pasadena, California, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

Henry and his wife and business partner Doris Marks Dreyfuss lived at 500 Columbia Street in a substantial family home in a wealthy district of South Pasadena (a very expensive dentist now works from the studio) set in lush, leafy grounds. It was situated up a hill, with barnlike garages that overlooked the modern studio. There was a small parking lot in front of the studio accessed by walking down a path from the 500 Columbia Drive entrance.

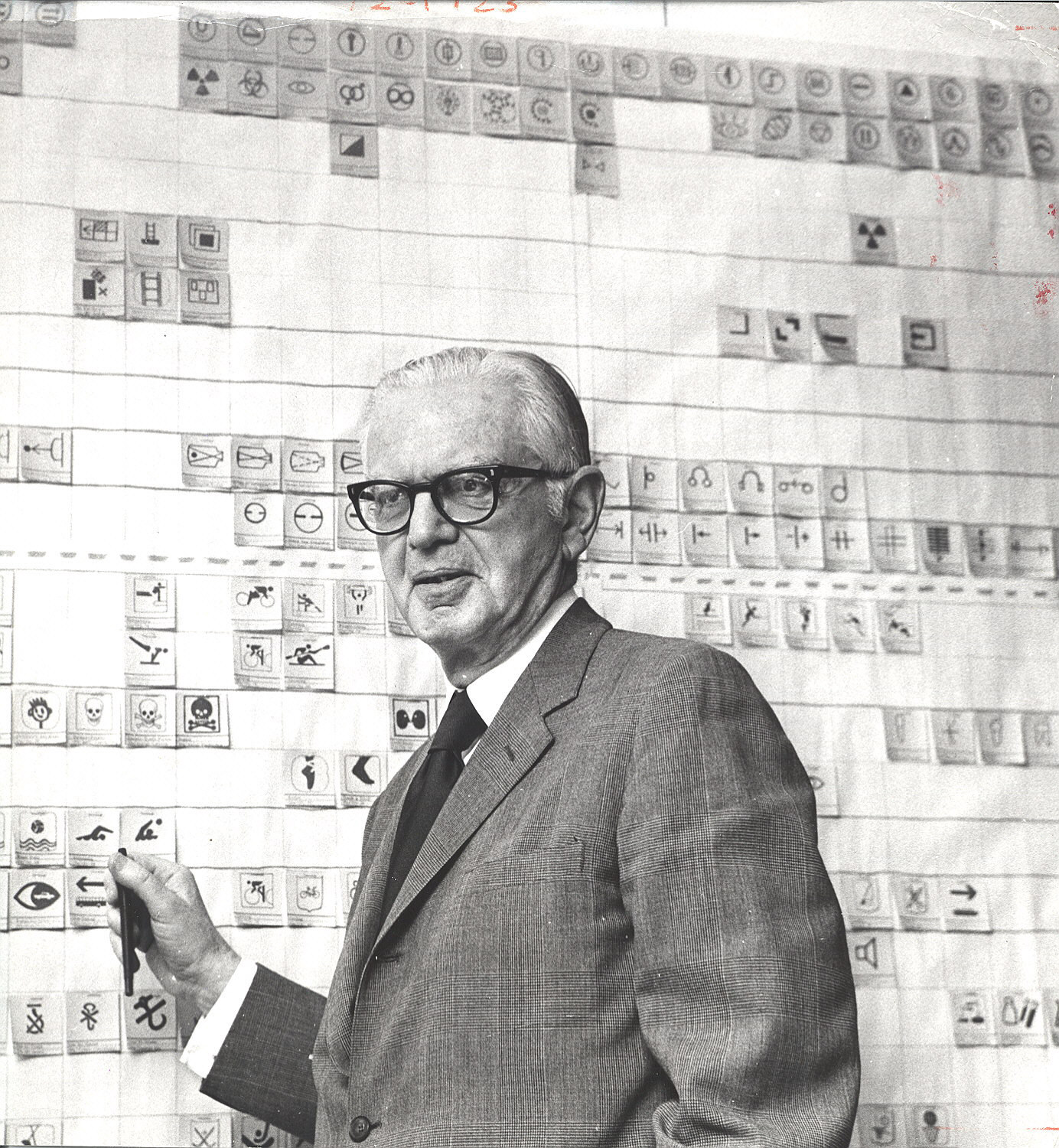

Pam described how the studio was configured. Henry had an office at the back, where he worked on a large table. Doris had offices at the front in the center, near the secretarial staff, next to project manager Paul’s office, where the famous “symbol wall” was located (fig. 3). Pam worked alone, tucked away in the back corner of the studio on the left-hand side, surrounded by upright drawing boards. She saw a little of what went on among the rest of the team.

Figure 3: Henry Dreyfuss in front of Symbol Wall, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

The Team

The original team consisted of Henry Dreyfuss, Doris Marks Dreyfuss, Paul Clifton (project manager), Kathryn Bray (secretary), Jeanette McFarland (secretary), and Pam. Later they were joined by George Ball, who worked on the editorial side of the book (Pam remembers him as a convivial colleague). They were later joined by two young women who worked on the Agricultural section of the Symbol Sourcebook (they may also have helped with pasting the symbols to artwork boards). The two young women were hired to help meet McGraw-Hill’s tight publishing deadline, on the realization that Pam could not complete the job of drawing all the symbols alone within the time frame. Archival correspondence between McGraw-Hill and Henry verifies this struggle to meet the deadline, but Pam was never put under any pressure, nor did she ever receive any criticism. She loved her work and happily worked seven days a week for most of the duration of the project. Henry and Paul were aware of her commitment to this role, which Pam said was the only job in her life that really mattered to her. It was an intense period, but she relished it. Pam remembers going home to her parents’ house for lunch, also washing her clothes while there. But apart from that, she worked all the time and parked her car in the parking lot at the front of the studio. The studio doors were unlocked, and she worked alone, tirelessly drawing symbols.

Pam didn’t see much of Doris Marks, who appeared unwell and never visited her part of the studio (Doris was in her late 60s at this point and had cancer). Doris was often found in Paul’s office, which was next to the secretary’s office. Kathryn Bray was secretary to Henry. Pam thought her a lovely woman (which rings true according to the warmth and humor seen in archival correspondence). Jeannette McFarland was the junior secretary and worked strictly in the secretarial area.

Pam’s job did not involve dealing with the huge amount of paperwork generated by the project (the Symbol Sourcebook archive consists of 26 large boxes full of correspondence—much of it is printed on very thin paper, which Henry used as a paper-saving measure—and they threw nothing away). There was also a substantial amount of airmail correspondence, along with a few telegrams and memos (on yellow paper). Doris and Paul, supported by the secretarial staff, organized the reference material for Pam to draw from. Pam was unaware of the intricate details of how Paul managed the job and constructed the symbol wall, but it was the place where he, Henry, and Doris would have their meetings and discuss the project. Henry never stopped working—he was always commenting on what was going on, and his lively and often humorous comments can be found throughout the archive. Pam had limited contact with Henry, but she commented on how calm and supportive he was, with a magnetic personality, highly creative brain, and great sense of humour.

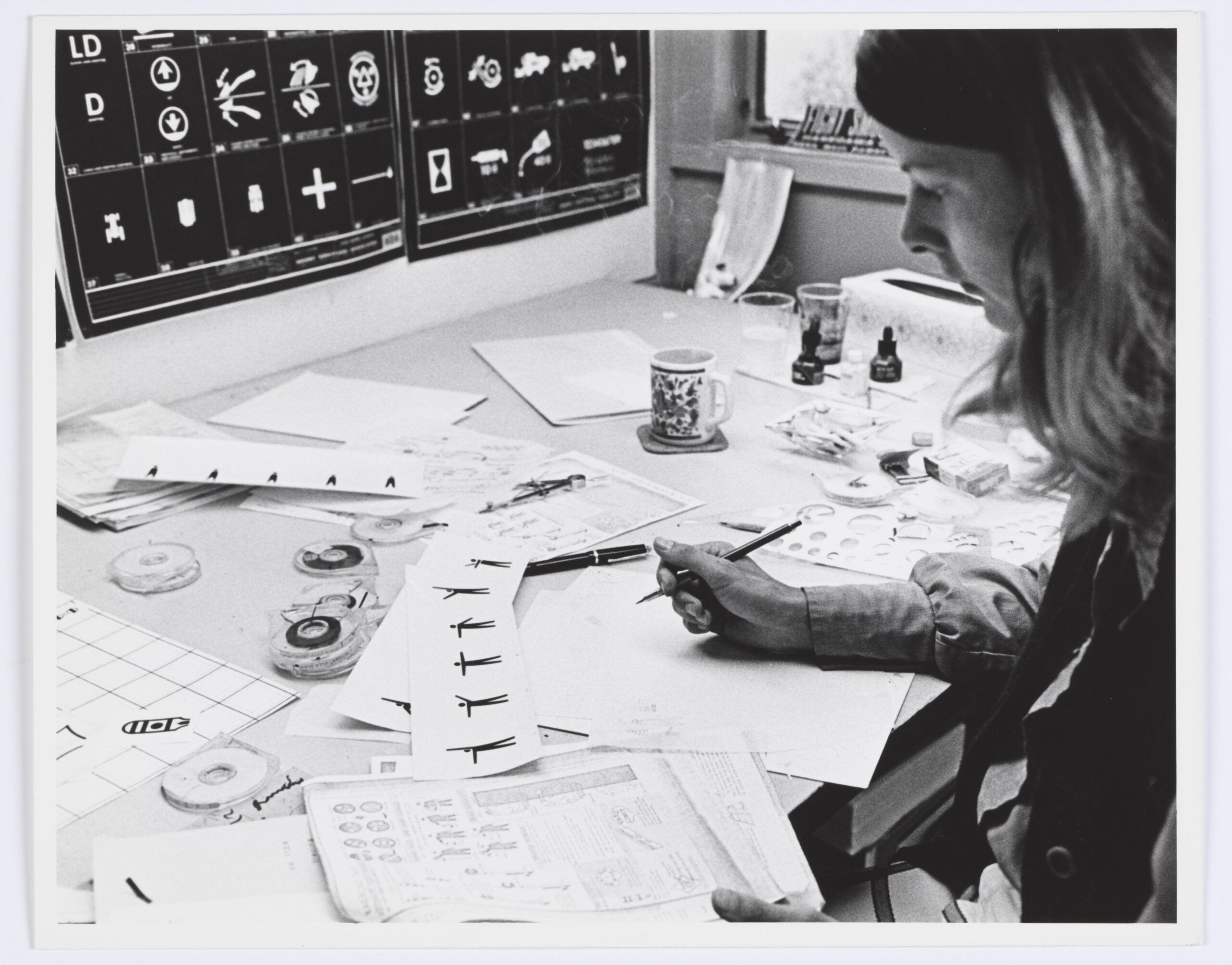

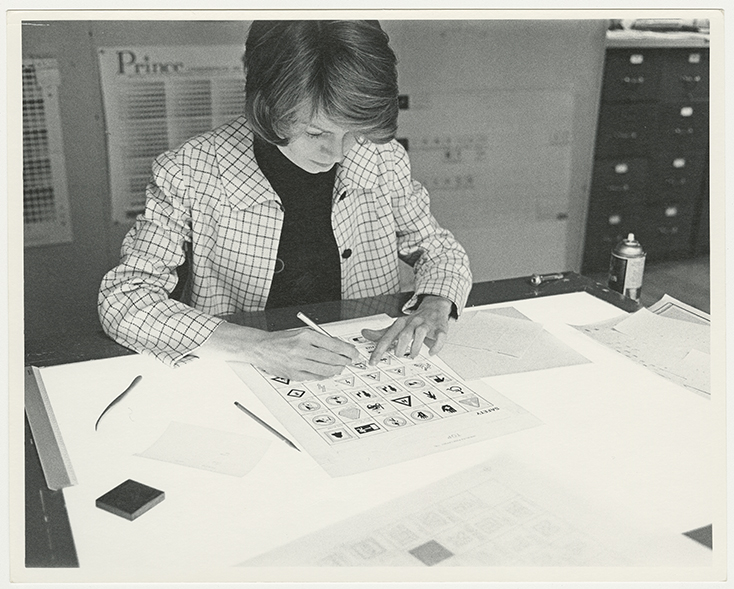

The Photographs

The team wore their most stylish clothes for the “candid” press photographs taken by a local Pasadena photographer for the Symbol Sourcebook, which she admitted were all staged. Pam is shown in many of the publicity shots, pictured with piles of files on her desk and a variety of drawing pens and ink. She originally had shoulder-length hair, but she cut it shorter because it got in the way of her work (figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Pamela Holaday Redrawing Symbols, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

Figure 5: Pamela Holaday Laying Out the Symbol Sourcebook, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

The Working Day

Pam drew the majority of the 3,000+ symbols in the Symbol Sourcebook, except for the large section of agricultural symbols (drawn by the two latterly recruited young women); those in the filler features at the end of each “Disciplines” section (drawn and written by Henry and retouched for consistency by Pam—he was unaware of this); those in the introductory Bliss and Isotype sections; and the symbols supplied by designers and large corporations as camera-ready artwork that didn’t need to be redrawn (such as Lance Wyman’s Mexico Olympic symbols and design manuals containing corporate signing systems such as that of American Airlines). Pam also stated that she didn’t draw the hobo symbols and suspected that Henry did.

Pam admitted that initially she felt out of her depth, as she knew nothing about symbols and didn’t have much experience in drawing. But her creativity and skill in draftsmanship is obvious from the highly accomplished artworks around her home, created despite her having no formal training in art or design. She threw herself into the task of drawing symbols with great enthusiasm and professionalism. There were no mechanical means of resizing available in the office—just drafting tables and oversized drawing boards.

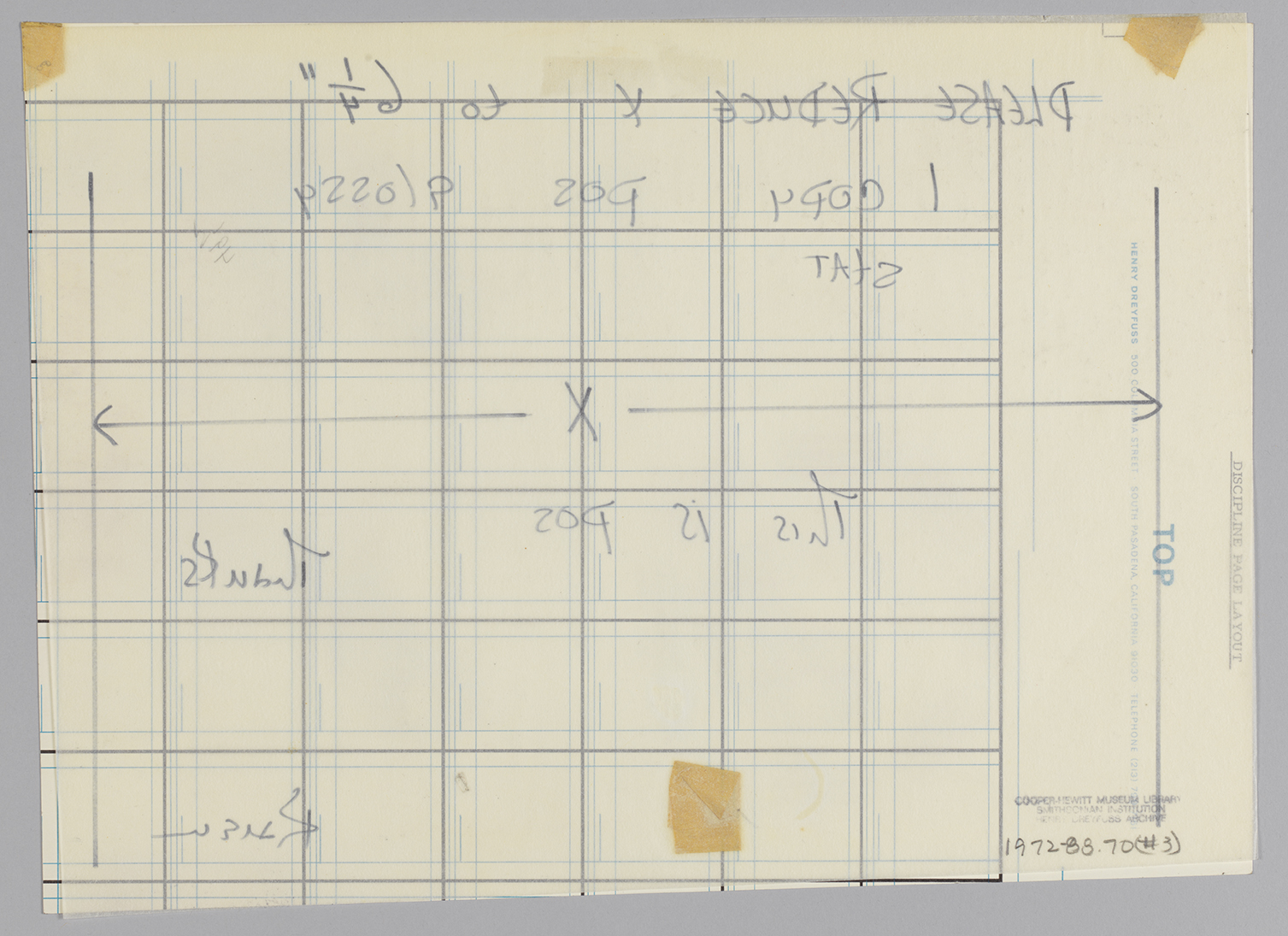

Initially, Paul introduced Pam to preprinted grid sheets with blue lines forming the boxes in which she would redraw symbols from the reference material provided. Her drawings needed to fit neatly into each box and be of consistent size and line thickness (fig. 6). The grid and page size had already been designed when Pam arrived. From archival correspondence in the working files, it appears that Paul supplied Pam with the reference material to draw the symbols that had been sourced by Doris Marks, Henry, and himself. Much of it was collected in response to the call for symbols in the Symbol Questionnaire (issued extensively to Henry’s work contacts and old clients from 1970 through 1971). But symbol references also came from the tens of thousands of symbols in Henry’s existing collection, which he had amassed over the previous three decades and which would form the symbol Data Bank that was to be the legacy of the project and was intended to be continually updated.

Figure 6: Design Drawing, Discipline Section Page Layout for the Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, ca. 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

When Pam arrived at work in the morning, she was greeted by an in-tray full of reference material she needed to draw symbols. She had little idea of the structure of the book or how the symbols fit together. Paul managed the book’s content. It was not a stressful situation, and Paul never told her what to do; she just got on with drawing the symbols, working at the back of the studio. The only area where Pam was allowed free rein to design symbols for the Symbol Sourcebook was in the Astrology section, where there were no preexisting standards. It was a solitary job. At that point, due to Doris’s illness, neither Henry nor Doris traveled.

The symbols Pam drew were collected by Paul, who (I presume) added them to the relevant discipline pages. They may also have been placed on the famous Symbol Wall in Paul’s office. This was a good representation of what was going on in Henry’s expansive mind. Paul was able to interpret what Henry was thinking; he was the practical facilitator of the project, and Henry needed him to realize his vision. Doris Marks was the perfect person to manage the project.

Pam referred to Paul, Henry, and Doris as PC, HD, and DM. Each of them used a different-colored pencil to add comments and initialize reviewed correspondence when it arrived in the mail (DM was red, PC was blue, and George Ball was green).

Paul and Doris handled the symbol collection, writing to organizations and individuals, and they continually sent out Symbol Questionnaires after 1970 to those they thought might provide new perspectives on symbols or any extra information about them. The Symbol Questionnaire originally went out to everyone in Henry’s extensive 40-year address book of former clients and associates, and he made new contacts by building on their knowledge and expertise. This is all documented in the six boxes of correspondence on symbol collection. The boxes contain correspondence (deftly filed in alphabetical order with support from a grant from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee) from such varied organizations as American Airlines; John Deere; Bell Telephones; and a variety of international designers, including Lance Wyman and Massimo Vignelli. Everything was kept, and it forms the archive.

Memories of the Dreyfuss Home

Henry, Doris, and originally their three children lived on a hill on their estate in a large, beautiful house surrounded by lush vegetation and paths to the garage. Pam visited the house only once (and never met the other members of the family), when Doris Marks invited her for lunch when her employment with them was reaching an end. It is clear from correspondence that both Doris Marks and Henry wanted to help Pam with the next step of her career. Pam described the Dreyfuss house as being tall, with large rooms and dark wood paneling. Lining the walls of the large hall were many beautifully designed, glazed, dark wood cabinets. They were filled with the couple’s collection of priceless, exquisite antiques of all sizes, worthy of any museum collection—Pam just wanted to touch them. Pam had had very little contact with Doris Marks during her work and admitted to feeling intimidated by the formality of the surroundings. Servants provided the food. Doris Marks was very kind and tried to make conversation, but Pam felt so uncomfortable in these unfamiliar surroundings that she was lost for words. This was not helped by the meal’s being served topped with a soft egg, something she could not eat! Her memory of this meal is very vivid, her parents always cooked food well. In hindsight, Pam suggested that Doris Marks was in poor health and needed the extra nourishment provided by the soft egg. Sadly, Doris’s health deteriorated, and this was Pam’s last visit to the house. Letters and notes written to Pam by Henry, both while she was working on the project and after she left, show that he really did want to try to help with her future career plans. Pam is aware that he and his wife didn’t try to do this for everyone, and it was obvious that Pam was a highly respected member of team.

Pam’s Life after the Symbol Sourcebook & Memory of Henry Dreyfuss

After the Symbol Sourcebook went to print (sometime in late 1971), the studio team was disbanded, and Pam needed to find a new job. She went to work for California State University, Los Angeles (Henry had many connections with this university). Her job was working with pathogenic bacteria, growing them in petri dishes, which she did for about 10 years and which was at least somewhat related to her background in science. She found the job easy but boring. She went back to study part time for a degree in education. After graduating, she taught three- to five-year-old children with special educational needs. She taught for 10 years with the help of a wonderful classroom assistant, until it was decided that someone was needed to teach physical education. So Pam once more went back to school and studied for a degree in adapted physical education for children with special educational needs. Pam worked in this role until she retired.

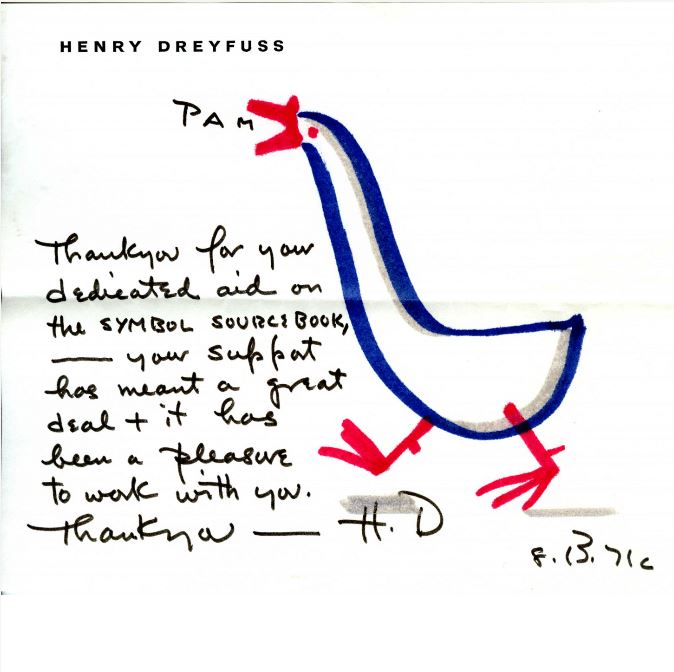

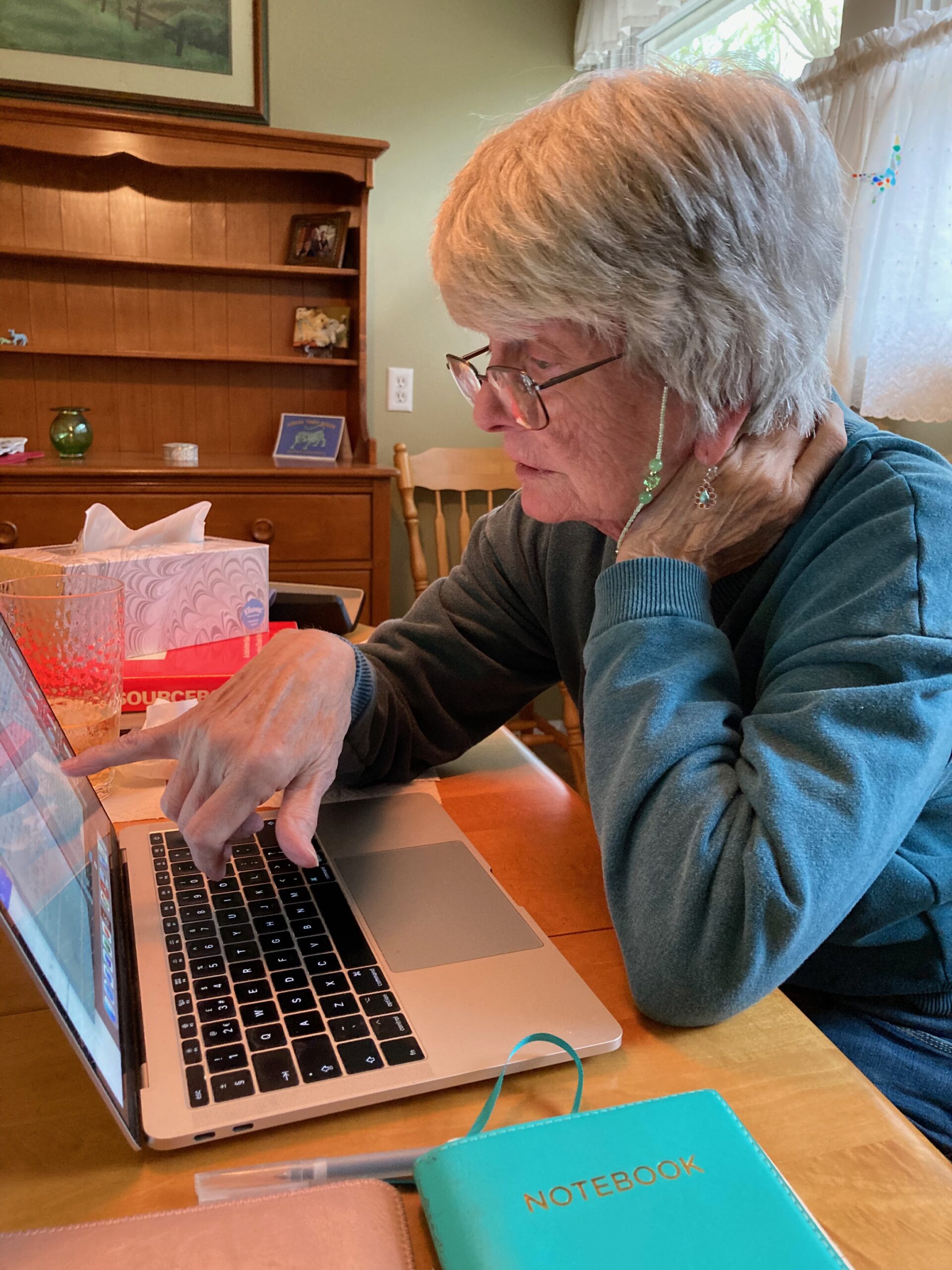

Henry left many amusing drawings on Pam’s desk, which she very kindly presented to me. She would secretly leave cookies on his desk, but it was obvious he knew who had left them. He also drew a Christmas card with a friendly snake and charming drawings of friendly geese (fig. 7). Henry’s and Pam’s mutual respect shines through in these drawings and notes. Henry kept in contact with Pam after her work on the Symbol Sourcebook was finished. He was concerned that she wasn’t happy in the microbiology lab. She didn’t feel it appropriate to reply to his letters until she was asked if she had spotted any corrections and spelling errors in the first edition of the Symbol Sourcebook (published in January 1972) that could be amended in the planned second edition. Serendipity brought forward a letter written by Pam to Henry that I found in the archives before my meeting with her. In the letter, Pam “critiqued” the book in an organized manner! She was laughing as she viewed the 50-year-old letter online and couldn’t believe her youthful audacity (fig. 8). Pam would have been the perfect person to spot corrections, given her attention to detail and knowledge of the overall project. She reported that she found no misspelled words, though Henry had joked in an earlier letter to her that he hoped the “Mistakes” folder didn’t get too fat!

Figure 7: Note, Henry Dreyfuss to Pamela Holaday, August 13, 1971; Courtesy of Pamela Holaday

Figure 8: Pamela Holaday, Pasadena, California, March 5, 2022

Pam pointed out that Henry was born on March 2, Doris Marks on March 3, and she on March 4. Pam never thought of Henry as her employer, which shows the open, easy manner he had with his team. That interpretation is reinforced by the notes left by Henry on Pam’s desk and the concerned notes he sent to her thanking her for her work, her kindness, and her commitment.

Sadly, on October 5, 1972, Henry and Doris took their own lives when Doris’s cancer became too painful to live with. An exhibition had taken place at the Hallmark Gallery in New York in early 1972, the first and second editions of the Symbol Sourcebook had been printed, and the third edition was planned. Henry had arranged for the archived materials from the whole of his working life (including all the papers, dummies, and correspondence from the Symbol Sourcebook) to be donated to Cooper Hewitt.

Pam remains deeply affected by their deaths. She felt that Henry’s life was cut short and that he still had a lot to give. She described his “peaceful, wonderful, tangible energy,” his larger-than-life intellect, and his role in redefining industrial design.

My interview with Pam will always stay with me. She made me welcome in her home, which I’m very grateful for. Her 18 months working on the Symbol Sourcebook from 1970 through 1971 was a time she remembers with great joy, though it culminated in great sorrow. In addition to learning that she drew nearly all the symbols for the book by hand and gaining a much greater insight into how the book was produced, I caught glimpses of Henry’s personality and his respect for Pam and the rest of the team’s tireless work on the project. Pam is formally thanked for her work in the book on page 251, and Henry and Paul both wrote dedications in her copy of the Symbol Sourcebook.

I found a surprising fact in the Leo Burnett folder in the archive: A feasibility study shows that in 1970, what was to become the Symbol Sourcebook was nearly taken to Leo Burnett’s Chicago head office to be produced (Henry Dreyfuss and Leo Burnett were firm friends going back many years). But plans changed because Paul wouldn’t move to Chicago and Leo’s health was failing, so Leo couldn’t give the project (which he passionately believed in) the time and attention he wanted to commit to it. Leo ends by saying that the project needed Henry as a guiding light to push it forward and that being associated with advertising could taint it. This turn of events gave Pam the job she relished in her hometown of Pasadena, and the world got the Henry Dreyfuss Symbol Sourcebook.

March 5, 2022

Interview with Pam Holaday

Pasadena, California, USA

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.