In observance of Pride month, Cooper Hewitt’s curatorial departments have selected a group of objects with LGBTQ+ stories to feature on the museum’s collection site. These objects are loosely connected by the theme of queer modernisms and are by LGBTQ+ designers.

Modernism is a style typically associated with early- to mid-20th-century design in Europe and the United States that focused on simplified forms, industrial materials, and form in service of function. The broad interpretation of modernisms through this object selection brings dimensions to this simplified definition, embracing art deco, midcentury craft, and Space Age modernism, while stretching into postmodernism and beyond.

LGBTQ+ identity developed and matured during this time as well, openly becoming part of modern life while at times facing waves of repression. Queer designers worked within accepted aesthetic styles, still pushing boundaries and queering design.

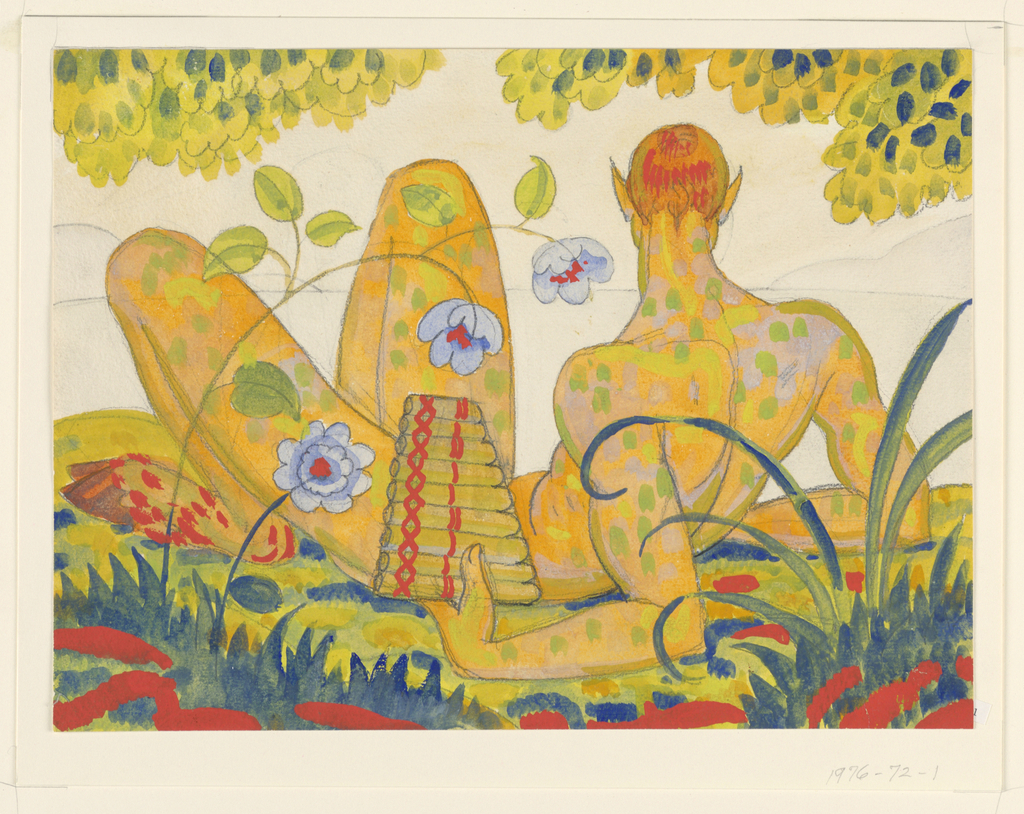

Drawing, Faun, circa 1920; Designed by Paul Thévenaz (Swiss, 1891–1921); Brush and watercolor, graphite on white paper; H × W: 24.2 × 32.7 cm (9 1/2 × 12 7/8 in.); Gift of Alice DeLamar, 1976-72-1

Paul Thévenaz worked primarily as a muralist, creating fantastical scapes for residential interiors. His figural imagery echoes bold, geometricized forms and use of bright color common in art deco design of the 1920s. This drawing of a faun was possibly made at the same time as the publication of The Canticle of Pan, a book of poetry written by Thévenaz’s partner, Witter Bynner.

The drawing was gifted to Cooper Hewitt by Alice DeLamar, an arts patron and lesbian heiress who quietly supported a circle of queer artists, including sponsoring a catalog of Thévenaz’s work after his early death.

Modernette Cuff Bracelet, designed 1948; Designed by Art Smith (American, 1917–1982); Copper, brass (alloy); H × W × D: 6.4 × 6 × 6 cm (2 1/2 × 2 3/8 × 2 3/8 in.); The Susan Grant Lewin Collection, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2016-34-102

Art Smith was active in New York City’s Greenwich Village from the late 1940s until the ‘70s. Part of the studio jewelry movement, Smith’s work was intended as “wearable art” and showcases materials wrought in abstract, biomorphic forms inspired by modern sculpture, dance, and jazz.

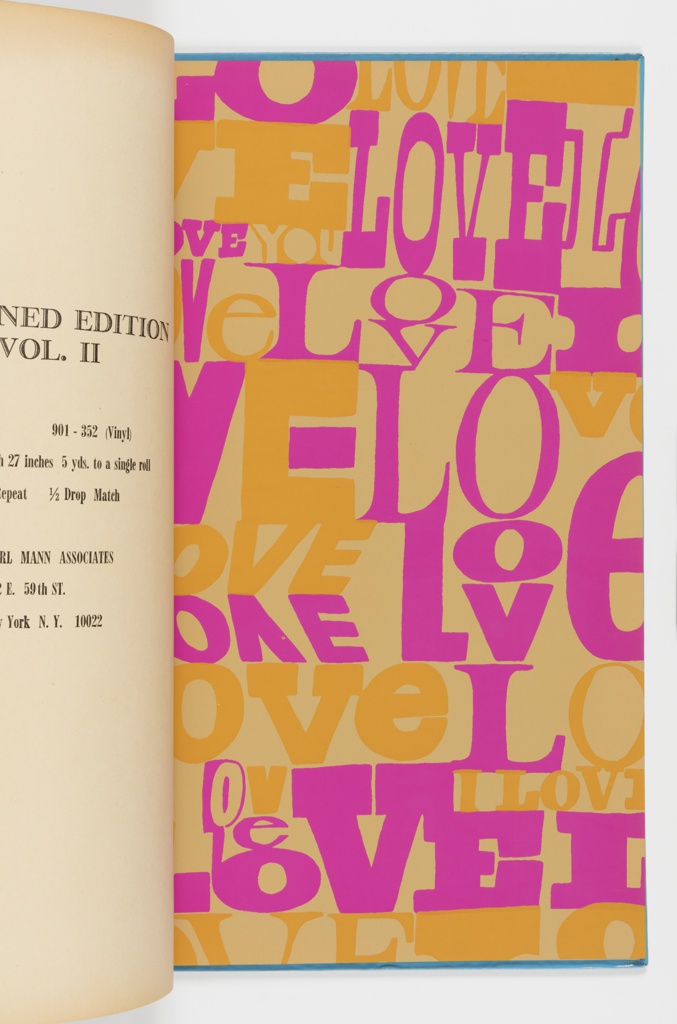

Sample Book, Combined Edition II, 1969; Designed by Jack Lenor Larsen (American, 1927–2020) and William Skilling; Manufactured by Karl Mann Associates (USA); Screen-printed paper, vinyl; Overall: 51 × 36 × 4 cm (20 1/16 × 14 3/16 × 1 9/16 in.); Gift of Karl Mann Associates, 1969-132-1-1/57

Jack Lenor Larsen was one of the foremost American modern textile designers. Like many designers, he branched out of his expected medium for collaborations. In this book of wallpaper samples designed with William Skilling for Karl Mann Associates, Larsen used a similar bright, bold color palette often found in his textile designs and abstract forms displaying a handmade imperfection. He was an advocate for the role of craft in modern design in a career spanning seven decades.

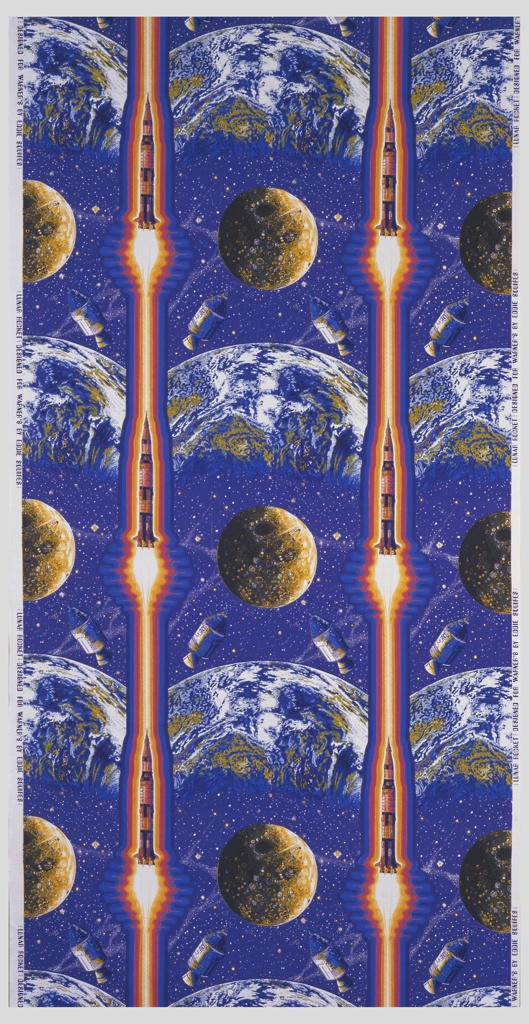

Textile, Lunar Rocket, 1969; Designed by Eddie Squires (British, 1940–1995) for Warner Fabrics (London, England); Printed by Stead McAlpin & Co. (Carlisle, England); Screen printed plain-weave cotton; H × W: 295 × 124.1 cm (9 ft. 8 1/8 in. × 48 7/8 in.); Gift of Eddie Squires and Richard Reiche, 1991-102-1

Titled Lunar Rocket, this textile by Eddie Squires celebrates the moon landing in 1969 and reflects the interest in the exploration of outer space from the 1960s. Squires was design director for Warner Fabrics and sought out trends in design and culture to update the company’s traditional, high-quality fabrics.

Squires donated this piece to Cooper Hewitt with Ruppert Richard Reiche, who was the partner of David Exley, textile designer and friend of Squires. Exley’s work is represented in Cooper Hewitt’s collection, including his intriguing Cat and Tinned Eye textile. Both Exley and Reiche passed away from complications related to AIDS between 1990 and 1991.

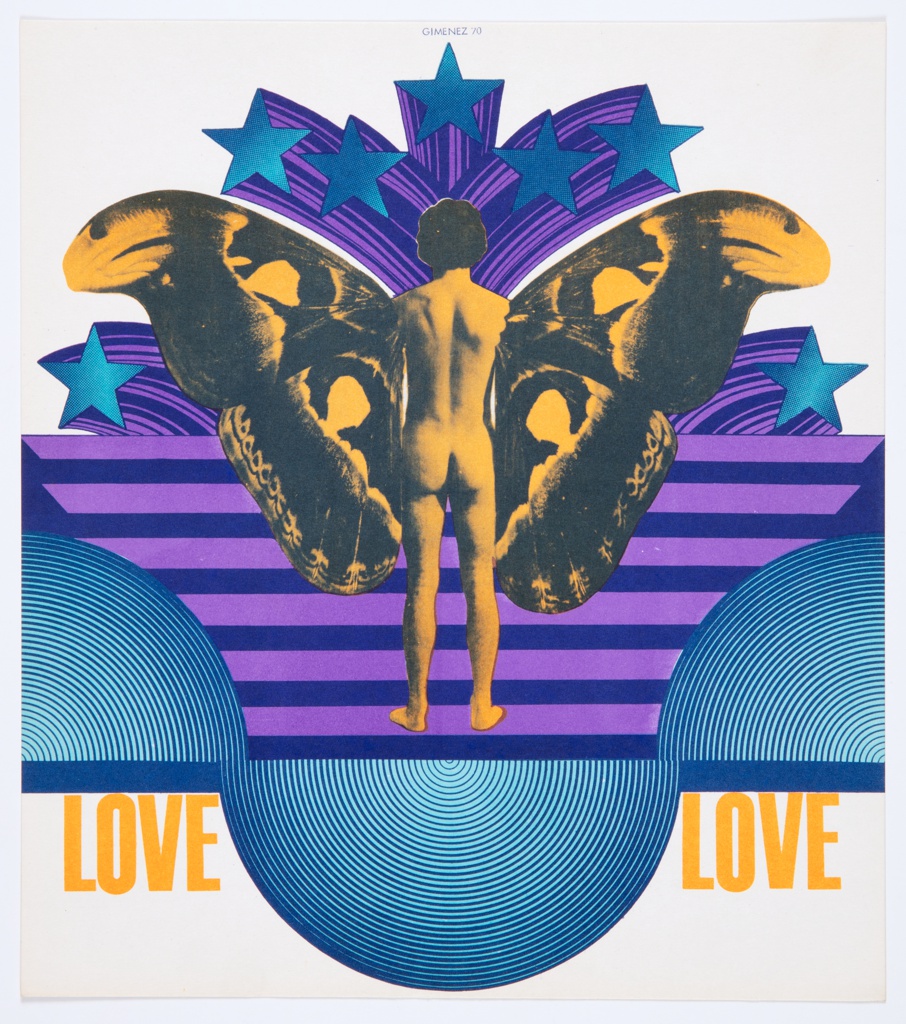

Poster, Love (Butterfly), 1970; Edgardo Giménez (Argentinian, born 1942); Screenprint on paper; L × W: 25.7 × 23.2 cm (10 1/8 × 9 1/8 in.); Gift of the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), 2021-29-16

Edgardo Giménez understood the power of a thirst trap. In promotional material for his design work, he included imagery of himself in boxer shorts, jockstraps, and harnesses, and freely indulged in homoerotic imagery. Giménez often used photo collage (including photographs of his own body) enhanced by bold color palettes to generate eye-catching imagery inspired by international artistic trends. Produced before Argentina’s military dictatorship and Dirty War, his work displays a modern, liberated approach to sexuality and the human body.

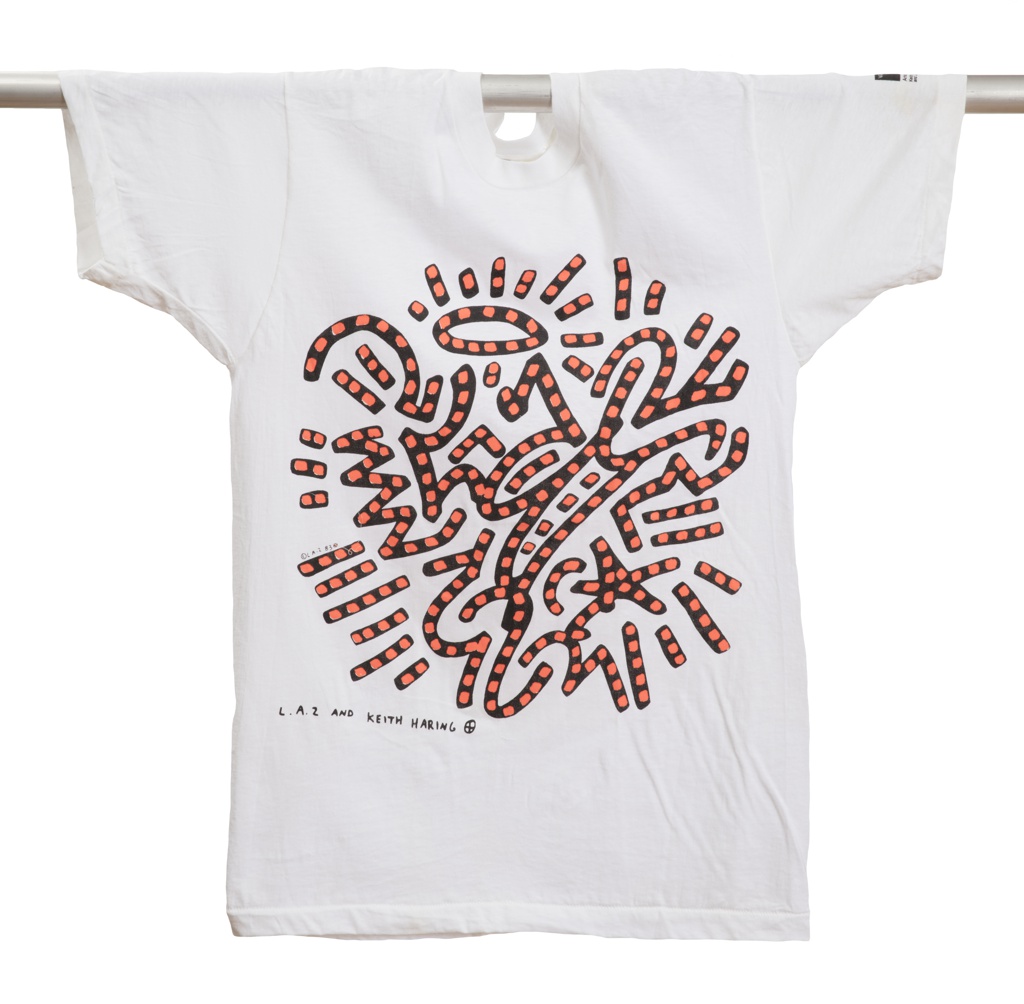

T-shirt, 1984; Designed by Keith Allen Haring (American, 1958–1990) and LA II (American, born 1967); Made for WilliWear Productions (New York, New York, USA); Screenprint on cotton; H × W: Approx. 76.2 × 50.8 cm (30 × 20 in.); Gift of Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation, 2022-39-1

Keith Haring’s animated, lively work—cut short by his early death related to AIDS—has become synonymous with 1980s New York, encapsulating the creative energy of the time and an unpretentious production of art. This t-shirt was produced for WilliWear Productions, lead by Black, gay designer Willi Smith, whose work aimed to bring art and fashion to everyday people on the streets.

Cosmos Floor Lamp, circa 1985; Designed by Dan Friedman (American, 1945–1995); Anodized aluminum, plastic, metal, rubber (casters); H × diam.: 39 × 43 cm (15 3/8 × 16 15/16 in.); Gift of Ken Friedman, 1997-19-3

While Dan Friedman started in corporate graphic design (remember the old CitiBank logo from your bank statement, anyone?), he transformed into a postmodern darling, creating daring, sometimes confusing, queer designs that challenged modern conceptions of graphics and interiors. Proportion is called into question and shape deployed seemingly erratically in Friedman’s fascinating, otherworldly designs. This floor lamp, measuring little more than a foot tall and equipped with wheels for mobility, screams for a radical space and a departure from modern living.

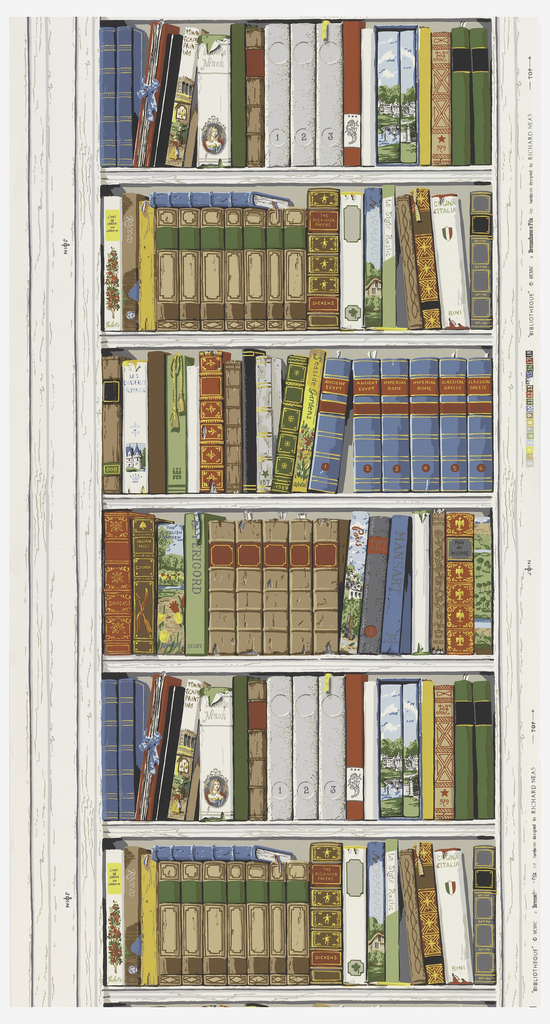

Sidewall, Bibliotheque, 1980–90; Designed by Richard Lowell Neas (American, 1928–1995); Produced by Brunschwig & Fils, Inc. (Aubusson and Bohain, France); Screen-printed paper; 266.7 × 86.4 cm (105 × 34 in.); Gift of Hank and Gladys Edelman, 1997-159-1

In the latest of the selection—and arguably stepping outside the confines of modernism—Richard Lowell Neas employs trompe l’oeil whimsy in mimicking the look of books on shelves in 2D on wallpaper. The design is a tongue-in-cheek rejection of the sanctity of the surface. Such illusionistic imagery—both witty and more traditionally decorative—was the cornerstone of Lowell Neas’s practice as both an artist and interior designer.

Matthew Kennedy is Publications Associate at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and History & Collections Chair of Smithsonian Pride Alliance.