Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

This article contains quotes with dated language that may be offensive to some readers.

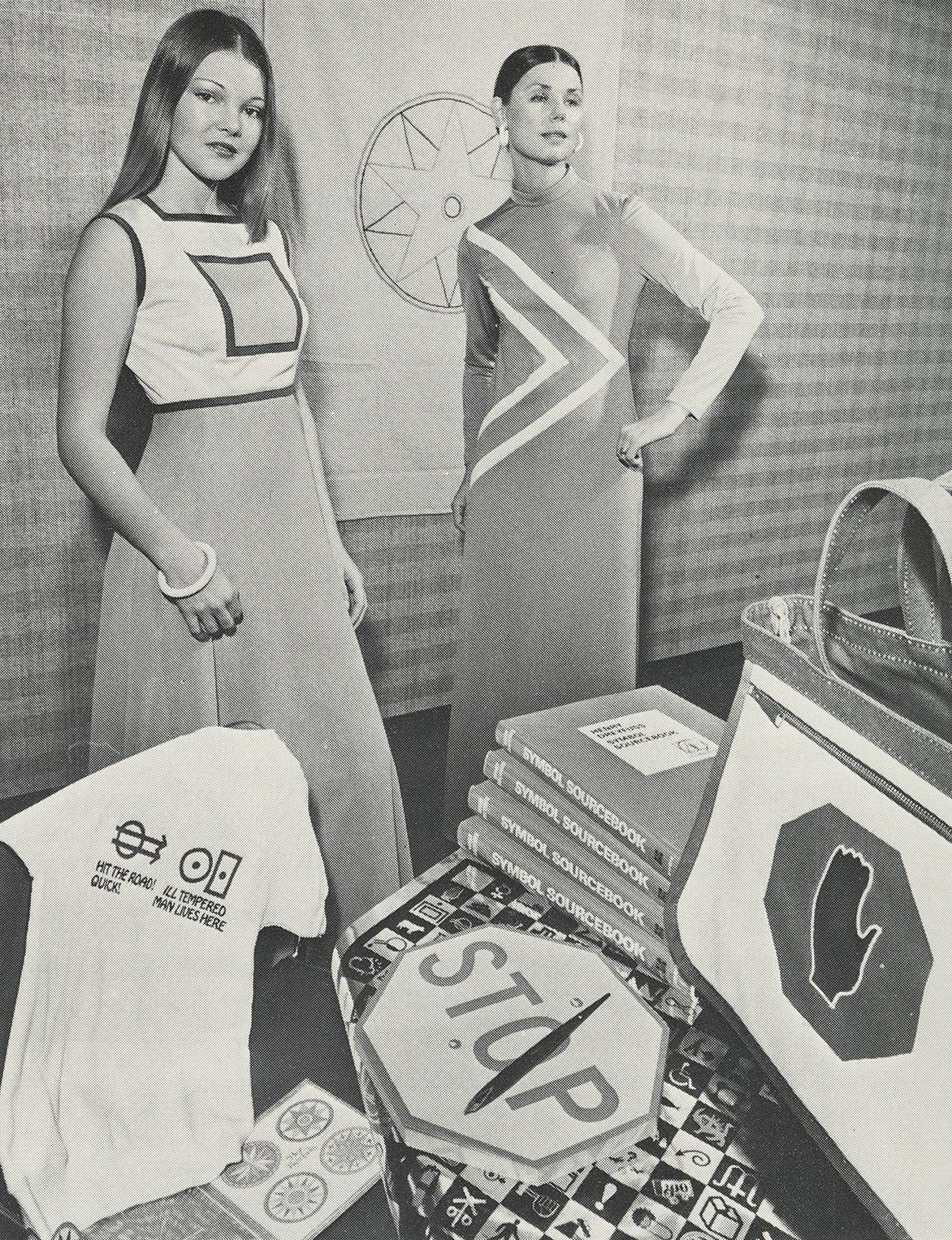

When Henry Dreyfuss signed the publishing contract with McGraw-Hill to proceed with the design and artwork of what was then known as “The Henry Dreyfuss Sourcebook of Symbols” on July 28, 1970, Dreyfuss’s business associate and friend Stanley Marcus of Neiman Marcus department stores sprang into action to promote the book by producing a wide range of symbol-inspired merchandise (Fig. 1), along with a specially bound Neiman Marcus edition of the Symbol Sourcebook. Neiman Marcus’s PR department also organized a punishing schedule of US-wide book signings, TV talk show appearances, and radio interviews from December 1971 through the first half of 1972. Working together, Dreyfuss and Marcus developed innovative ideas for a selection of eye-catching, symbol-inspired fashion and home wear items, launched in Neiman Marcus’s 1971 Christmas catalog and featured in all Neiman Marcus window displays in January/February 1972 to coincide with the publishing of the Symbol Sourcebook on January 11, 1972.

Fig. 1: Neiman-Marcus Symbol Merchandise, “Symbol Sourcebook,” Communication Arts, 14 (1), 1972, p. 72; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

But promotion of the Symbol Sourcebook began even before Dreyfuss signed the publishing contract with McGraw-Hill. In May 1971, Dreyfuss connected Marcus with New York–based Terry Hicks, the product manager of McGraw-Hill, with the possibility of using Neiman Marcus’s mailing lists to promote the book. Dreyfuss was also eager to promote the book to European organizations using Marcus’s contacts, but those contacts did not extend to Europe. It was originally Marcus’s idea to apply symbols to merchandising, but from archival correspondence it was clear that Dreyfuss was wary of copyright issues. He also suggested showing the merchandise at Halls Shopping Center in Kansas City, Missouri, where Halls Exhibition Gallery had staged a retrospective exhibition on Dreyfuss’s work—Designing for People—from June 3 through July 10, 1971. Work on the Symbol Sourcebook is mentioned as being his latest project.

Dreyfuss understood the retail sector; he loved shopping and saw it as a means of understanding people’s motivations. It was therefore quite logical that he would use retail to promote what could be seen as quite an esoteric book to a wider audience. In a letter to Marcus dated May 7, 1971, Dreyfuss supplied a long list of possible merchandising ideas: “I’d say the ideas could be unlimited. We could help supply the symbols to a designer or, if the designer could call on us, he (or she) could do the choosing. Where do we go from here?” Dreyfuss’s ideas for possible merchandising show the playful attitude he had in considering the possibilities of what the range could include:

Bed sheets, Pillow Cases International traffic symbols. Could or could not have “double meanings”. Yield, Stop, Soft Shoulder, Turn Right, Caution, Danger, Exit, Enter, etc., etc. OR a pattern of male and female symbols

Ashtrays Reversible ones, No smoking symbol on convex, Permit smoking on concave [Figs. 2, 3, 4]

Coasters, Glasses, Coffee Mugs, Chinaware Any number of applications, traffic, Male on some, Female on others [Figs. 5, 6]

Raincoats Clouds and what they mean

Umbrellas A pattern of umbrellas (means Keep Dry)

Costume Jewelry Pendants, Belts, Earrings, Cufflinks, Fast, Slow

Ties Alchemy, Traffic symbols

Pajamas (someone has done a rather crummy all-over pattern on men’s Pajamas)

Scarves We have a collection of HEX wheels – some warding off evil, some attracting luck, abundance, wisdom, etc., etc. Perhaps one big wheel on a scarf or a pattern of them explaining meaning under each wheel.A 15th Century manuscript has turned up concentric staffs of music (like Row-Row-Row your Boat). The circular card on which the music was inscribed was rotated on a table, around which were seated the signers. How about Frere Jacques?

Bathmats Slippery when wet.

Table Mats Either a pattern or a single symbol at big scale on a circular mat

Children’s Apparel Either all-over pattern material OR big applique

Shopping Bags Would the symbols used on John Deere farm machinery be good stenciled on blue jeans? OR the new recreational symbols done for our National Parks (designed by Chermayeff) be good for camping outfits? We have a great collection of HOBO symbols that tramps scratch in chalk on fences to guide their buddies. They can read like sentences (or not) and I think could be successfully applied to any number of things.

Kids We have a series of symbols designed so that youngsters can understand them – before they learn to read: DO NOT TOUCH (fire) (sharp) CAUTION re street crossing, traffic light etc., etc.

Fragile This symbol is a cracked goblet and could be used on some ladies’ (women’s) wear!

Fig. 2: Symbol Ashtray: Caution, 1972; Designed by the Office of Henry Dreyfuss (South Pasadena, California, USA); Distributed by Neiman Marcus (Dallas, Texas, USA); Plastic; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-129-1; Images © Smithsonian Institution

Figs. 3, 4: Symbol Ashtrays: Up and Prohibition, 1972; Designed by the Office of Henry Dreyfuss (South Pasadena, California, USA); Distributed by Neiman Marcus (Dallas, Texas, USA); Plastic; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-129-2, 3; Images © Smithsonian Institution

Fig. 5: Symbol Coffee Mug: Male, 1972; Designed by the Office of Henry Dreyfuss (South Pasadena, California, USA); Distributed by Neiman Marcus (Dallas, Texas, USA); Earthenware, glaze; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-126-a,b; Image © Smithsonian Institution

Fig. 6: Gypsy Teacup and Saucer, 1972; Designed by the Office of Henry Dreyfuss (South Pasadena, California, USA); Distributed by Neiman Marcus (Dallas, Texas, USA); Earthenware, glaze; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-128-a,b; Image © Smithsonian Institution

In a handwritten letter to Marcus dated June 24, 1971 (on Admiral Club letterhead), Dreyfuss thanks his friend “Stan” for “being so generous in providing the ‘Kick off’ platform for the Symbol Sourcebook” and supplies a concise description of the book for the copywriter to use for the Neiman Marcus Christmas catalog text:

a) Forward by R. Buckminster Fuller

b) Table of contents is presented in 18 languages – the theory being that once you are led to a discipline you should be able to ‘read’ the symbols

c) SYMBOLS are identified in 3 ways

- by DISCIPLINE i.e. architecture, agriculture, astronomy etc., etc.

- by MEANING a very complete alphabetical index

- by a most unique (never been done before) GRAPHIC FORM. Thus, if you see a symbol out of context + can’t look it up alphabetically you can find it in this section. For we have all the circles in one place, all triangles, all human forms etc. etc. It is a kind of ‘visual index’ that then refers you back to the actual disciplines in which a particular symbol belongs.

d) Perhaps the COLOR section will be of particular interest to N. M. patrons. We have found a good compilation of the meaning of colors.

In the same correspondence, Dreyfuss describes the “Color” section of the Symbol Sourcebook: “This section is a ‘beaut’ (+ printed in full color) you can find out what blue means in a Persian rug or what is inside a pipe when it’s painted blue. I hope this will mean something to your fashion industry . . . I really hope this collection will start a real effort to standardize symbols. A woman should find symbols for the same meanings identical on the dashboard of her car as on her washing machine. We seem to have hit the jackpot as far as time is concerned—our mail is ferocious and from all over the world with people enquiring or contributing and the letters from USA government agencies as well as European governments come in great quantity.” (Before signing off, Dreyfuss asks pardon for his scribble, saying that veteran comedian Bob Hope is seated in front of him—which shows the circles in which Dreyfuss was mixing!)

On June 25, 1971, Marcus sent a copy of Dreyfuss’s letter in an internal memo to his colleague John Mashek, asking him to send Dreyfuss’s description to the buyer and the copywriter and to eventually use it for training staff in the various stores. On June 26, he wrote a similar memo to Kay Kerr that illustrates Marcus’s deep understanding of the symbol project:

My friend, Henry Dreyfuss, is completing a book which McGraw-Hill will publish in January. It will be called a ‘Dictionary of Symbols’. The book will cover all of the symbols used by all of the countries for a wide variety of subjects ranging from communications as noted on the back page of the brochure. The index will be printed in eighteen languages. We’re going to use it in the Christmas Catalogue for January delivery since the book won’t come out until January.

It has occurred to me that since this has such graphic appeal that we might launch the book in January with a set of windows backed up by a select group for merchandise in which symbols have been used for design. For example, I can see a half of dozen coordinated sports outfits utilizing a printed symbol fabric printed in red, white and blue or any other combination you might like; blazers with symbols embroidered on a pocket, scarfs with a symbol design printed over it and even going into hi-ball glasses decorated with symbols and playing cards. I’d like to see enough for windows in all of the stores and with the merchandise from an apparel point of view probably concentrated in one department, preferably sportswear. I’m enclosing a copy of Henry Dreyfuss’ letter which was inspired after my conversation with him in which he outlined some further ideas. After you’ve had a chance to study this won’t you give me a quick reaction. If we’re going to do it, now is the time to get started on it for a January resort promotion. I haven’t discussed this with any of the merchants or buyers but will await your reaction.

These are the words that appear in the Neiman Marcus 1971 Christmas catalog, which goes back to Dreyfuss’s core motivations for designing the Symbol Sourcebook: “The word for the future, however, may well be found in Henry Dreyfuss’ Symbol Sourcebook ($39.50), a visionary compilation of symbols, modern and ancient. Mr. Dreyfuss offers the world a possible solution to simplified communication. He suggests a universality of symbol language that may well be the beginning of standardization of information, direction, or instruction in the ever nearing world of tomorrow.”

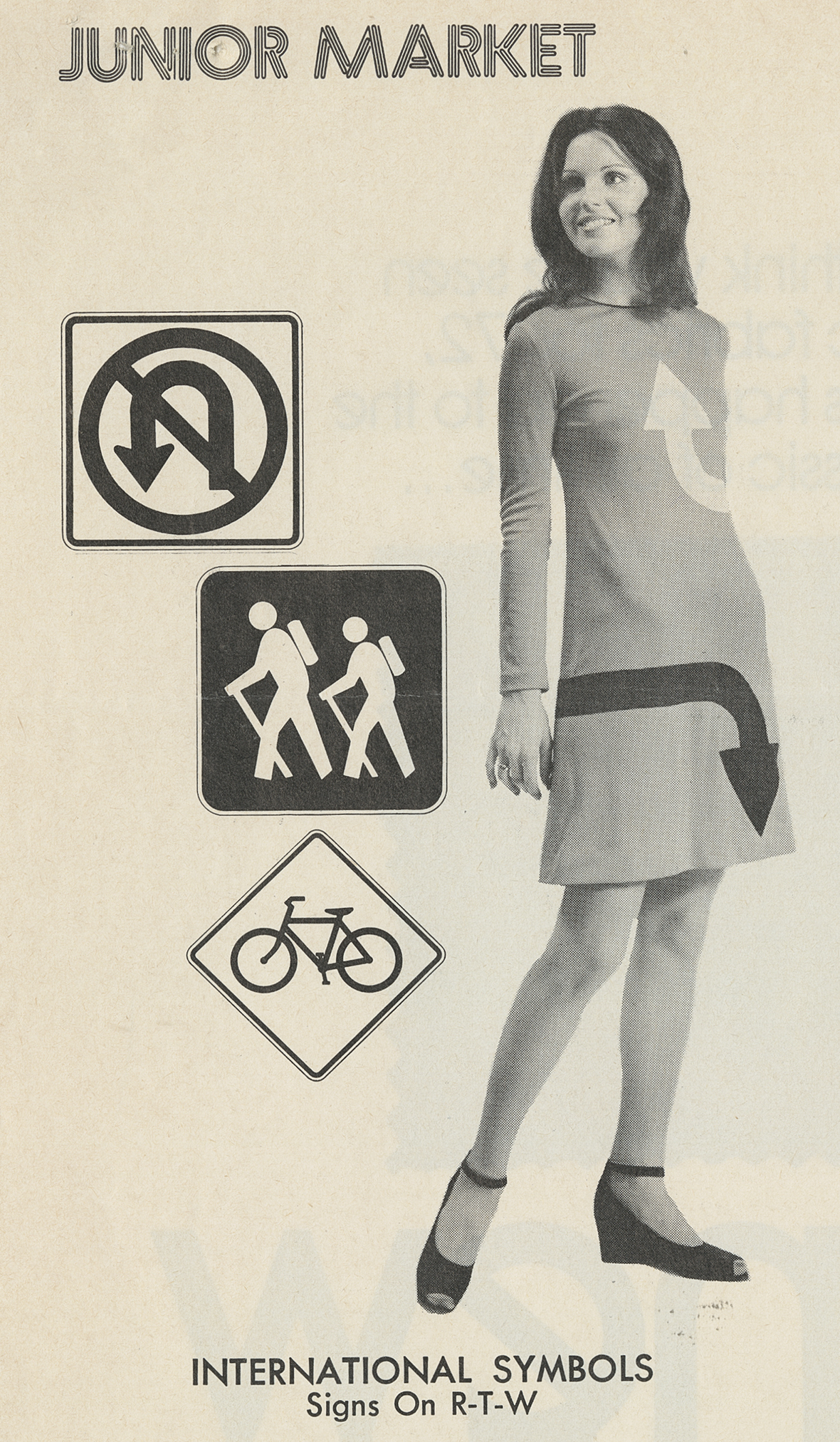

Fig. 7: Magazine Clipping, “International Symbols: Signs on R-T-W,” Clothes, January 3, 1972, p. 42; Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Image © Smithsonian Institution

On November 10, 1971, Marcus reported to Dreyfuss, “They are going ahead with fabrics expect to make men’s sport shirts, symbols on jewelry, hex symbols on needlepoint, hobo symbols on T shirts and smocks, the arrow on dresses and lots of symbols on raincoats, etc.” Marcus viewed the first sketches and samples of the merchandise in New York on November 22, 1971. In a letter to Dreyfuss dated December 30, 1971, Marcus stated that Neiman Marcus had invested $175,000 in symbol-inspired retail covering 50 different departments. In the same letter he enclosed a clipping from Clothes magazine that shows the arrow mini dress (Fig. 7).

In December 1971, even before the Symbol Sourcebook had been printed and the merchandise was available, Dreyfuss set out on an intense series of promotional trips to Neiman Marcus stores in Dallas, Houston, and Fort Worth. “Mr. Dreyfuss will be here tomorrow from 11.30 – 1.30 in the Stationery Department, Downtown, to autograph his extraordinary Symbol Sourcebook Neiman Marcus limited edition new book.” Dreyfuss in-store book signings are documented in press ads showing sketches of the outfits, accompanied by lively descriptions that promote both the Symbol Sourcebook and the merchandise, which highlight the types of synthetic fabrics used in the early 1970s. Does anyone still have any of these items anywhere in their attics?

With thanks to Ann Peterson, Curator of Photographs, DeGolyer Library, for her research assistance in the Stanley Marcus Papers.

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.

One thought on “Signs of the Times: Neiman Marcus’s Symbol Merchandise”

Dianne Rowell on September 8, 2023 at 10:26 pm

I graduated high school in 1970 in S California and had already discovered Mt Dreyfuss from a book in our library. I was so interested, and being able to buy it, I began copying whole sections in longhand. I wanted to be an Industrial Designer and no one knew what that was.

Time passed, and looking back, I know I wouldn’t have had the skills (math, sciences), I thought, to become an Industrial Designer. I did pursue other creative employment.

In 1984, our son Jonathan was born (we live in S Oregon) and like any mom, I shared my interests in design and architecture. In the fall of ‘03, he began his journey, first at Pasadena CC and then Art Center College of Design, also in Pasadena. He majored in product design and is an Industrial Designer. (One of my greatest thrills is when he told me I “mom, you could’ve done it”.

Over time, I learned of Eva Zeisel while she was still alive, one who didn’t have the aid of computers etc to do her work.

I realize I guess I had no excuse!

After graduation, Jonathan first began working for a consultancy in SF called frog, and Google on both coasts. Presently, he is the Design Director at the Cartier Lab in Williamsburg Brooklyn.

He also designs furniture, currently manufactured by HBF.

jonathanyoshidarowell.com

During this past spring, we did visit Mr Dreyfuss’ exhibit and I was thrilled. Also, eventually I found a copy about(?) Mr Dreyfuss before our son was born.

I’ve prevailed upon you I know, but I felt I had an interesting tale.