Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

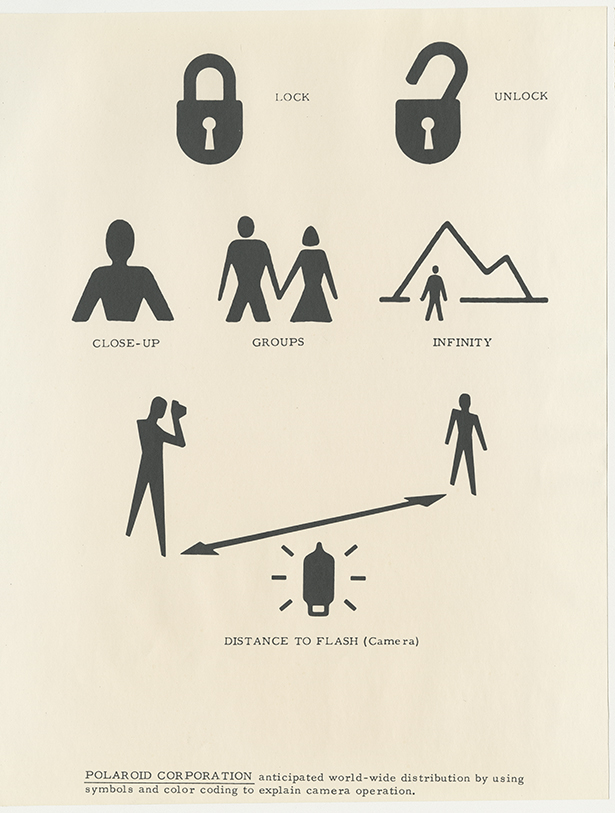

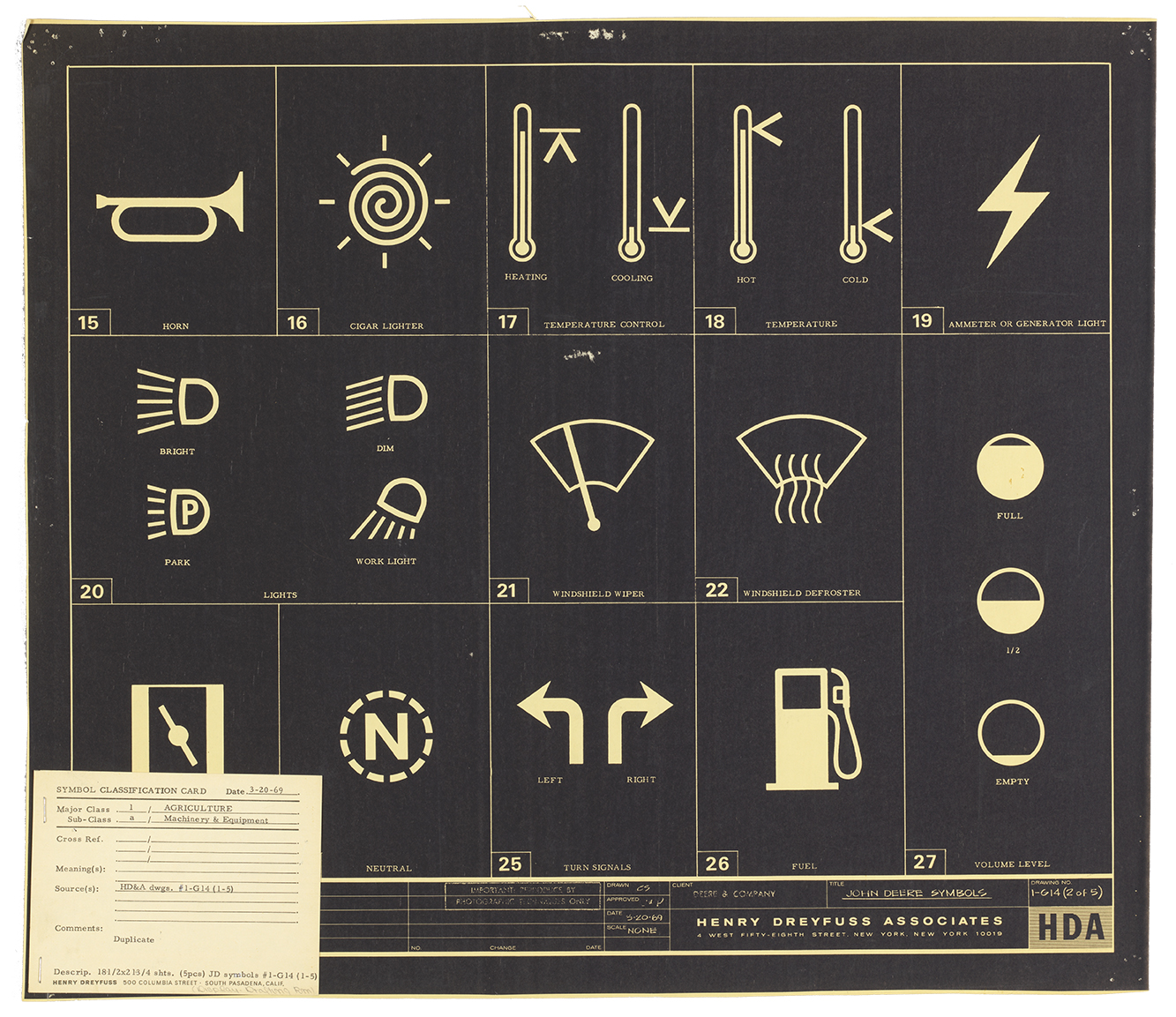

Henry Dreyfuss knew everyone. His vast network of clients and business associates extended back to his early days as a theatrical designer and read like a “Who’s Who” of the cream of American society from the 1930s to the 1970s. So it was no surprise that when he seriously took on the challenge to collect as many international symbols as possible in the mid 1960s for his Data Bank (out of which the Symbol Sourcebook grew)[1] that he should go to his network first for symbol information. After all, he had designed many symbols for clients throughout his long career as an industrial designer for organizations such as Polaroid (Fig. 1), Singer, and John Deere (Fig. 2) to name but a few. This starting point provided a huge number of symbols and background information on origins and usage, but it also enabled Dreyfuss to expand his network with client referrals for potential new symbol contacts. This is the basis of the intricate web of correspondence that is found in the Symbol Sourcebook archive. Some symbol requests were written quite formally by Dreyfuss and Paul Clifton (always citing the person who had recommended them if they were referrals), but many personal requests were hand-written by Dreyfuss, sometimes on Plaza Hotel notepaper where he always stayed when he was in New York. He would drop phrases stating that he had just returned from lunch with Mildred Constantine (influential assistant curator and curatorial consultant at the Museum of Modern Art from 1943 to 1970) or that comedian Bob Hope was sitting near him at a gala event. Many typed letters concluded with friendly personal greetings to wives and families suggesting that they should all get together for dinner soon. These letters show how gregarious and personable Dreyfuss was and how he truly enjoyed being part of such a vibrant cultural society.

Fig. 1: Symbols for Polaroid Corporation, circa 1969; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 2: Poster, John Deere Symbols, YEAR TK; Diazoprint with printed card; 47.6 × 55.2 cm (18 3/4 × 21 3/4 in.); Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-1-13

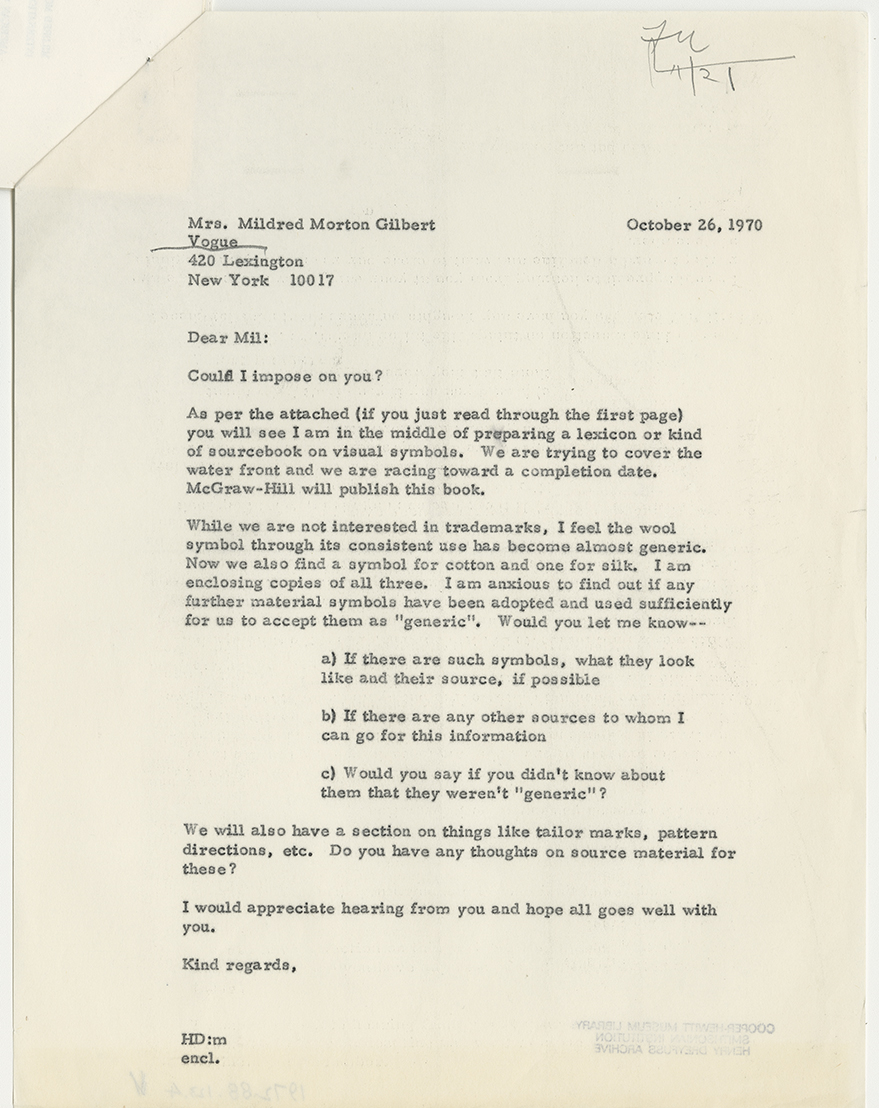

So it was no surprise that Mildred Morton Gilbert (1901–1992), International Executive Editor of Vogue magazine from 1966 to 1974, was one of the friends he leaned on to collect symbol information and find innovative ways to promote the Symbol Sourcebook to wider audiences—in this case 1970s Vogue readers.[2] In the archive, I came across correspondence from October 1970 to September 1971 sent between Dreyfuss and Gilbert (who Dreyfuss refers to as “Mil”). The correspondence from Dreyfuss not only asks if Gilbert can supply any symbols and related information from the fashion industry, but also provides commentary on how the book production was progressing. But Dreyfuss’s request to promote the book in the pages of Vogue—an idea supported by Mil—reveals a rather embarrassing incident that took place in Vogue offices on Lexington Avenue in New York City.

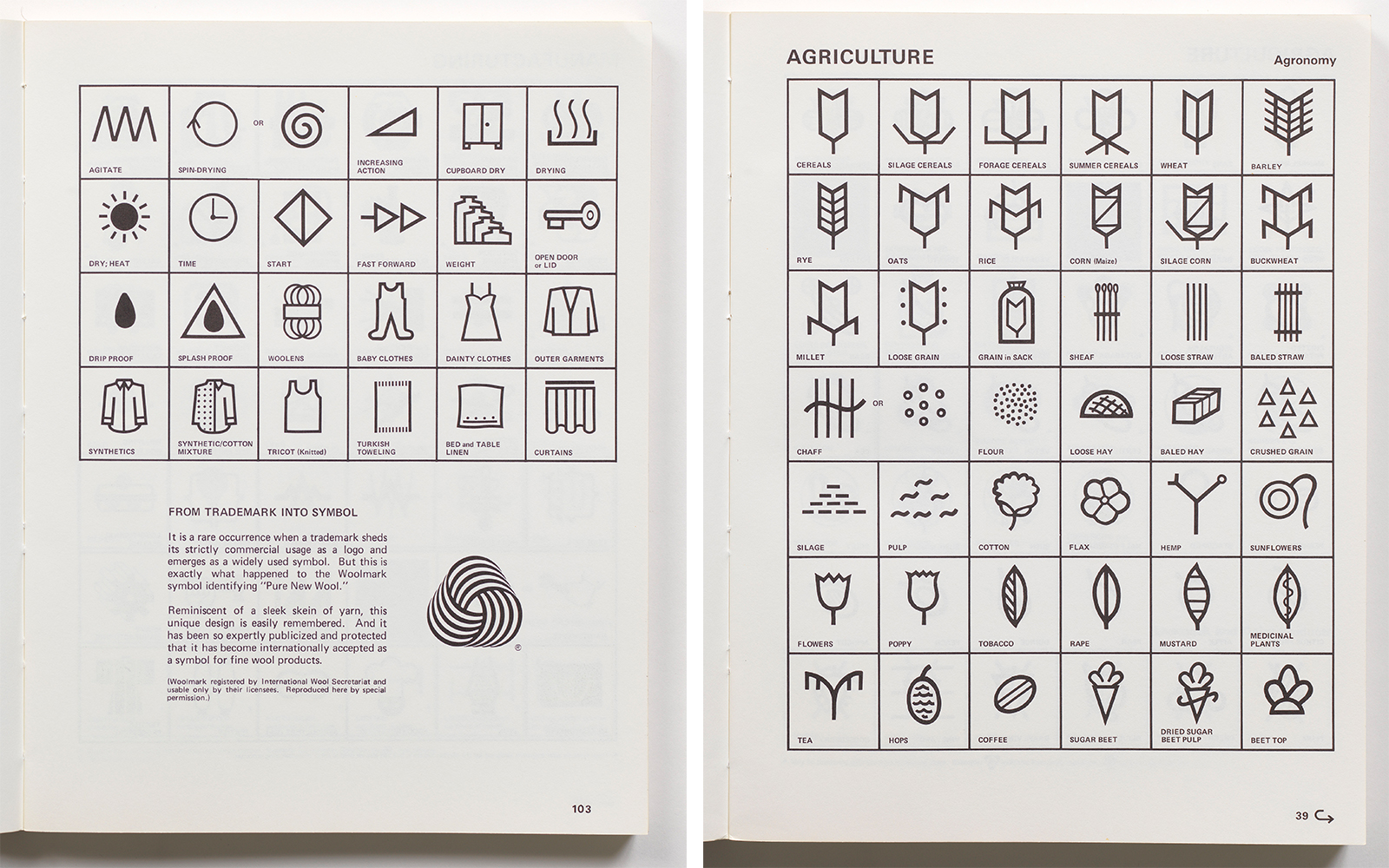

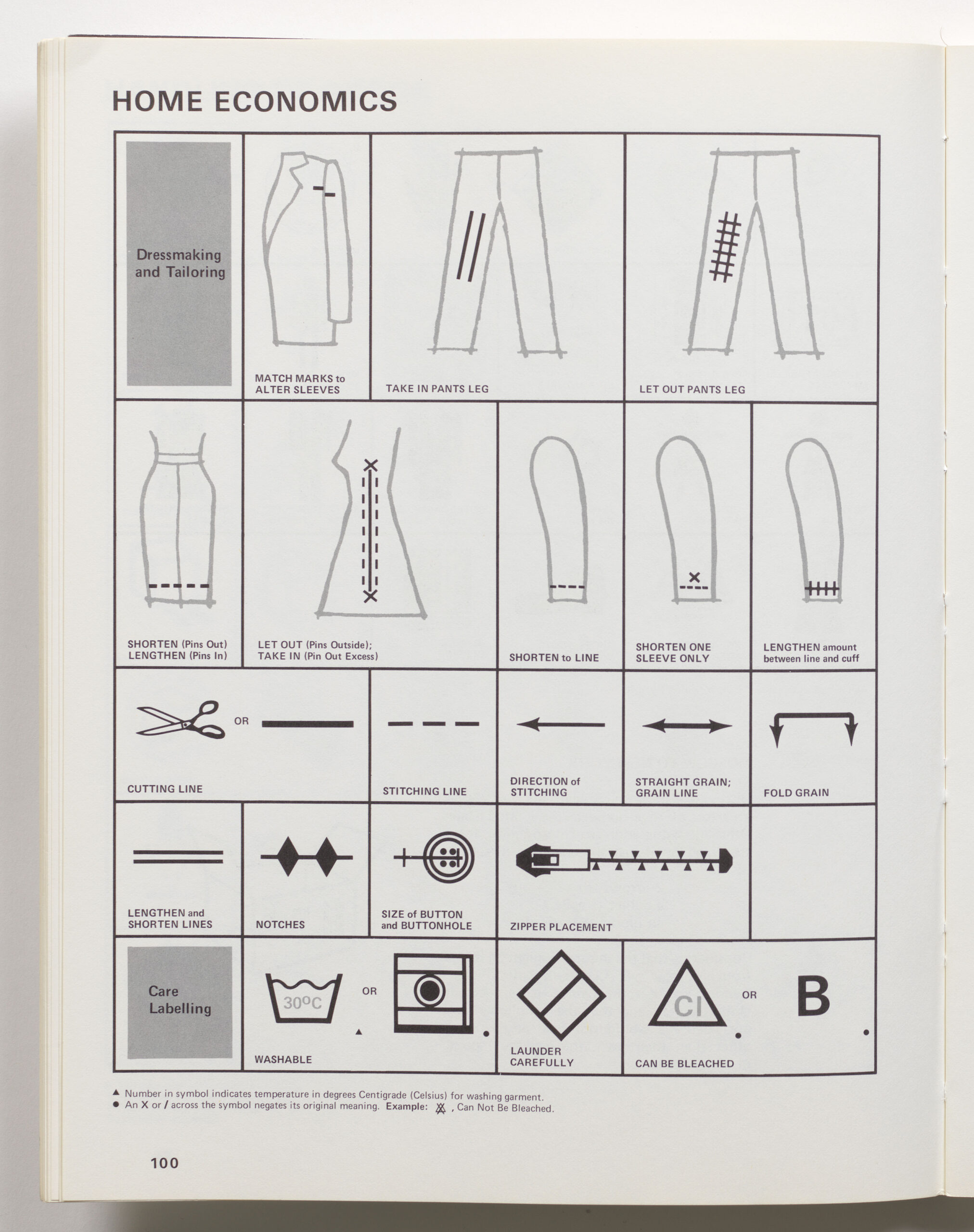

On October 26, 1970, Dreyfuss wrote to Gilbert (Fig. 3) with the phrase he often used with friends to start correspondence: “Could I impose on you?” He explained, “I am in the middle of preparing a lexicon or kind of sourcebook on visual symbols. We are trying to cover the waterfront and we are racing toward a completion date. McGraw-Hill will publish the book.” He went on to make it clear that he was not interested in trademarks, and although the wool symbol as a trademark (Fig. 4) had become generic through consistent use, he was interested in finding symbols for other materials such as cotton and silk (both appear in the final book, Fig. 5) and if they were also used sufficiently to be accepted as “generic.” Dreyfuss intended to include tailor’s marks and pattern directions (Fig. 6), asking Gilbert if she had any source material to help. She responded in November 1970 saying that she had circulated Dreyfuss’s requests for more information. This was a crucial time in the book production schedule as the research phase needed to move into the artwork phase to meet McGraw-Hill’s stringent deadlines. Doris Marks (Dreyfuss’s wife and business partner) wrote to Gilbert on November 10, 1970, saying, “As to symbols, let us know PDQ [pretty darn quick] if you get any dope [information] for us. This place is a madhouse, with symbols coming out of every corner and deadlines rearing their ugly heads. Hope you are not the same!”

Fig. 3: Letter, Henry Dreyfuss to Mildred Morton Gilbert, October 26, 1970; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 4: “From Trademark into Symbol,” Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive; Fig. 5: Cotton Symbol featured in “Agriculture” section of Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 6: Dressmaking and Tailoring Symbols featured in “Home Economics” section of Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Gilbert was true to her word and contacted her associates about fabric symbols. Mrs. Ingersoll of Condé Nast Publications directed the team to American Fabrics Magazine, and a Mr. Reinhardt found two widely used symbols for linen and mohair (neither of which appear in the Symbol Sourcebook, as Dreyfuss wrote in a pencil note that they were “Pretty far-fetched for our book”). Gilbert’s associates were unable to provide Dreyfuss with any more symbol information.

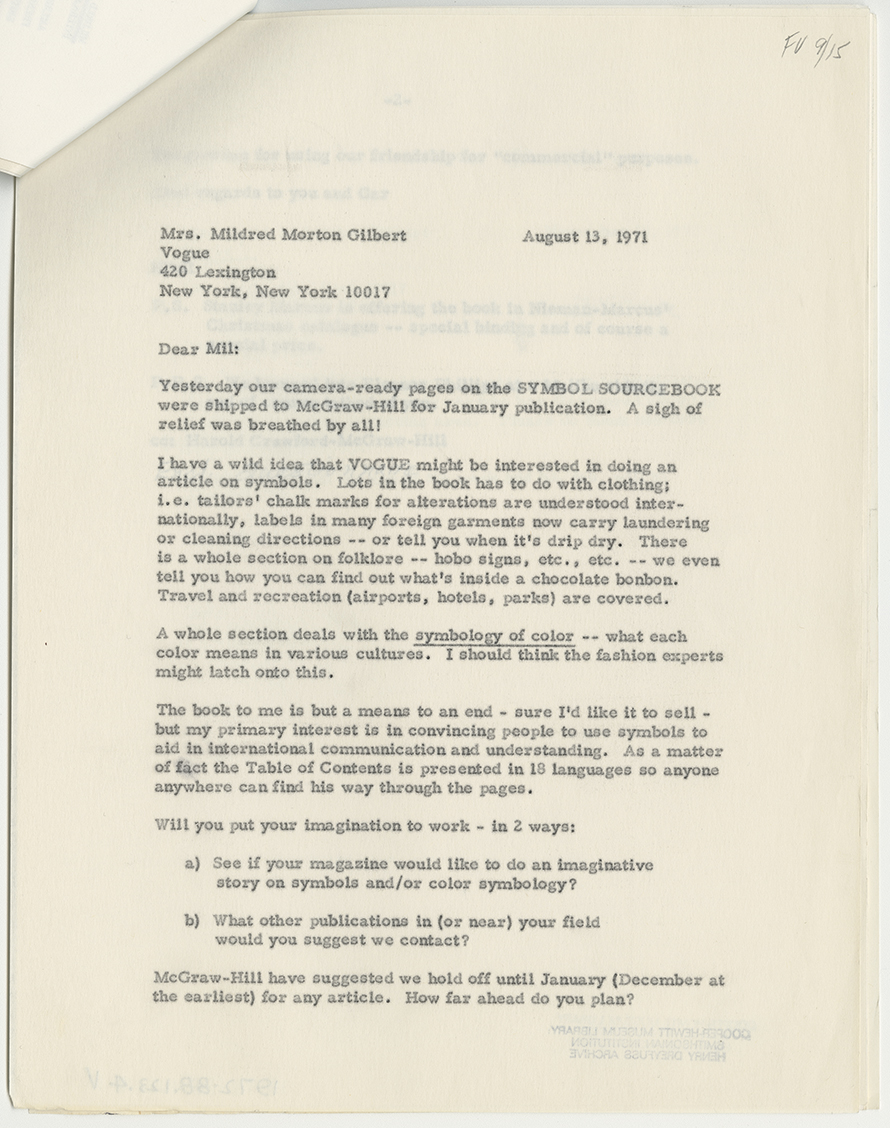

Friendly correspondence resumed in August 1971 keeping Gilbert up to date with progress: “Yesterday our camera-ready pages on Symbol Sourcebook were shipped to McGraw-Hill for January publication . . . —A sign of relief was breathed by all!” By this time, Dreyfuss was focusing on innovative methods to promote the book and again turned to Gilbert proposing:

“I have a wild idea that Vogue might be interested in doing an article on symbols. Lots in the book has to do with clothing: i.e., tailors’ chalk marks for alterations are understood internationally, labels in many foreign garments now carry laundering or cleaning directions—or tell you when it’s drip dry. There is a whole section on folklore—hobo signs, etc., —we even tell you how you can find out what’s inside a chocolate bonbon. Travel and recreation (airports, hotels, parks) are covered.

A whole section deals with the symbology of color—what each color means in various cultures. I should think the fashion experts might latch on to this.

The book to me is but a means to an end—sure I’d like it to sell—but my primary interest is in convincing people to use symbols to aid in international communication and understanding. As a matter of fact, the table of contents is presented in 18 languages so anyone anywhere can find his way through the pages.”

Dreyfuss ends by asking Gilbert if Vogue could include an imaginative story on symbols and/or color symbology (we would call this an “advertorial”) and if she knows of any other similar publications who might be interested in such articles (Fig. 7). He envisaged the Vogue article appearing in December 1971 at the very earliest. The intention was to send galleys (printed proofs) of the book to Vogue associate editor Kate Lloyd to gain a good understanding of how the article would work.

Fig. 7: Letter, Henry Dreyfuss to Mildred Morton Gilbert, August 31, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

But this is where things started to go wrong. It was holiday time and Kate Lloyd was on vacation, so a Mr. D. McConathy was tasked with meeting Dreyfuss and putting the plan into action. Dreyfuss had to cancel the first meeting but rearranged a new appointment with McConathy. The following is taken from a handwritten letter sent to Gilbert on September 28, 1971, which describes Dreyfuss’s brief meeting with McConathy, which was apparently terminated very quickly.

“Dear Mil:

My first impulse was not to bother you—my second is that you’d better get the story from the horse’s mouth. The Editor was not available to meet so I was put on to Mr. McConathy for a drink. But had to cancel, so went to see him by appointment today. He received me in the waiting room and asked to see “my work”. I had brought along a big dummy the result of many years’ effort and suggested we find an empty office. He explained that he looked at everyone’s work in the waiting room—I explained “Not mine!” Maybe because I spent the first half of the morning with the Chairman of AT&T and the second half with the Chairman of American Airlines, I couldn’t understand my reception or lack of it. What a way to run a railroad! I’m sorry if it causes you any embarrassment, sending love.”

In his defense, in a pencil note from a phone call between Marks and Kate Lloyd’s secretary, McConathy said he viewed everyone’s work in the waiting room, and he was sincerely interested in the Symbol Sourcebook, but had not realized that the HD who he was meeting was “THE HD.” Gilbert’s response on October 27, 1971: “I’m embarrassed and disgusted, and I can’t say anything more—Mil”.

Dreyfuss knew everyone, but evidently not everyone knew him. Archival correspondence ends after Gilbert’s response, and there is no evidence that Vogue published any articles directly relating to Dreyfuss’s work with symbols and color symbology at the time. Maybe due to a combination of Dreyfuss’s exasperation with the situation and Vogue’s embarrassment?

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Notes

[1] There were 20,000 symbols in the Data Bank in 1972 when the Symbol Sourcebook was published.

[2] Dreyfuss was was no stranger to designing women’s magazines. He redesigned McCall’s magazine and was responsible for the design and layout from 1932 to 1944. He also used this magazine to promote the Symbol Sourcebook to children in September 1972 in “Betsy McCall Learns Symbol Talk.”

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.