Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

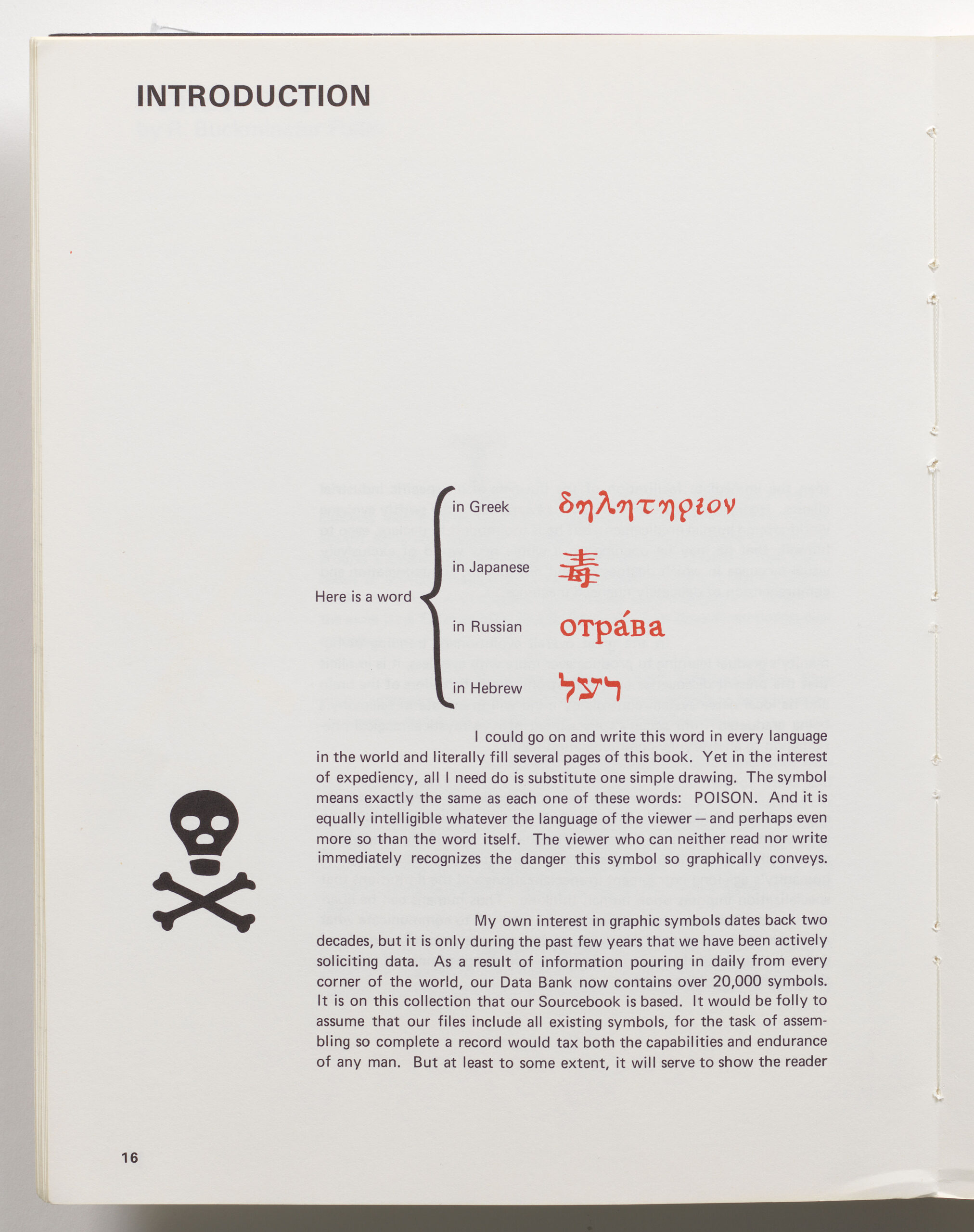

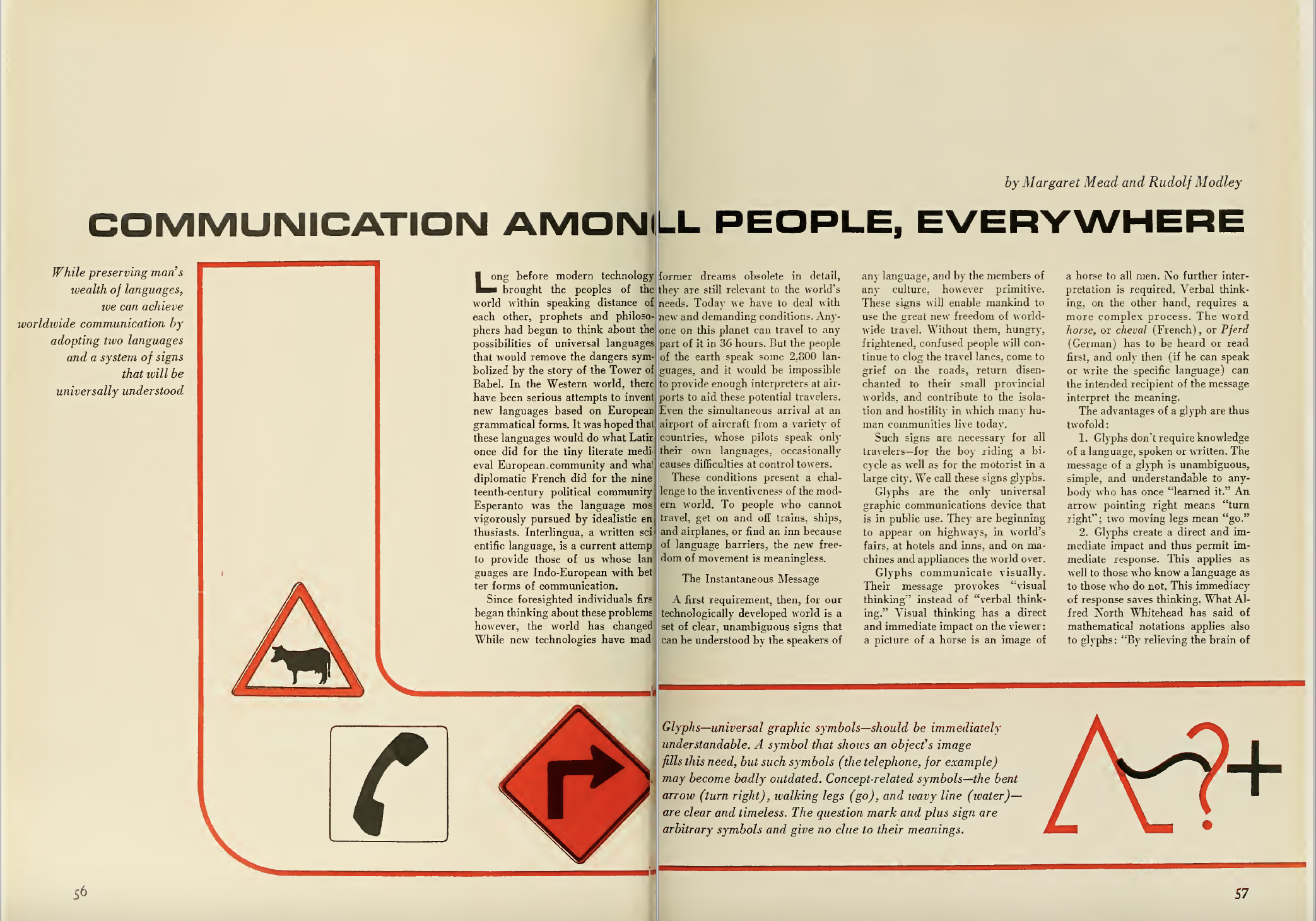

In 1972 Henry Dreyfuss published his Symbol Sourcebook, introducing it with: “Announcing the first tool to help break the communication barrier the world over.” It was not just a collection of symbols classified according to discipline, shape, and color, but also a cleverly designed cross-referencing system allowing the user to understand how symbols could be used to communicate in an increasingly visual (but not multi-lingual) world (Fig. 1). Dreyfuss did not consider his book a dictionary—as it was impossible to include every symbol in existence—but as a step toward a world where “universally understandable graphic symbols” could be used as effective tools to facilitate communication. This is a fascinating concept born out of an era known as “the jet and communications age” where the use of symbols was expanding fast due to more affordable international travel and trade, but also the underlying threat of the Cold War. In response, organizations such as UNESCO, the United Nations, and the Fund for Advancement of Education were supporting projects to promote peace and internationalism; the United Nations celebrated their 20th anniversary by naming 1965 as “International Co-operation Year.” Communicating through symbols was seen as the way to promote both peace and prosperity, reinforced by articles such as Natural History magazine’s August 1968 article “Communication Amongst All People Everywhere” written by anthropologist Margaret Mead and graphic designer Rudolf Modley of Glyphs, Inc. who introduced the concept of a set of universally understood “glyphs” that everyone in the world should learn (Fig. 2).[1]

Fig. 1: Introduction, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 2: “Communication Amongst All People Everywhere” by Margaret Mead and Rudolph Modley, in Natural History, August 1968; Courtesy of the National Museum of Natural History Library, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

Dreyfuss’s approach to “breaking the language barrier” was much more pragmatic. Many of the letters sent out by Dreyfuss and his team to collect symbols from organizations were accompanied by two symbol publications to give potential contributors an idea of the reasons why Dreyfuss was collecting symbols and the underlying ideas behind the project. These publications (sent out from early 1969 onward) were reprints of United States of America Standards Institute’s (USASI) October 1968 edition of The Magazine of Standards (Vol. 39, No. 10) article “Symbols: Communicating Without an Accent,” written by Dreyfuss to serve as a “summary of our current study,” and IBM’s November–December 1968 edition of THINK Magazine (Vol. 34, No. 6) containing science writer George A. W. Boehm’s article “A New Sign Language—Straight Ahead.” The following text reviews these two documents.

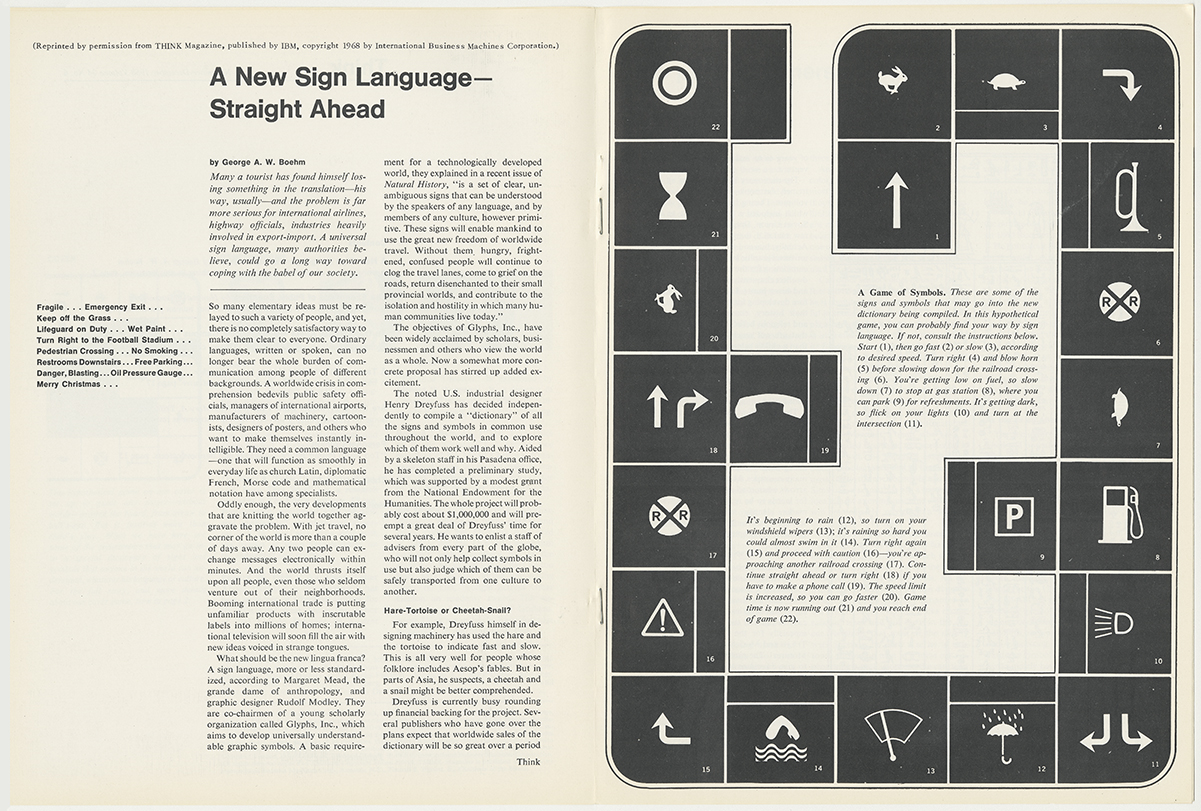

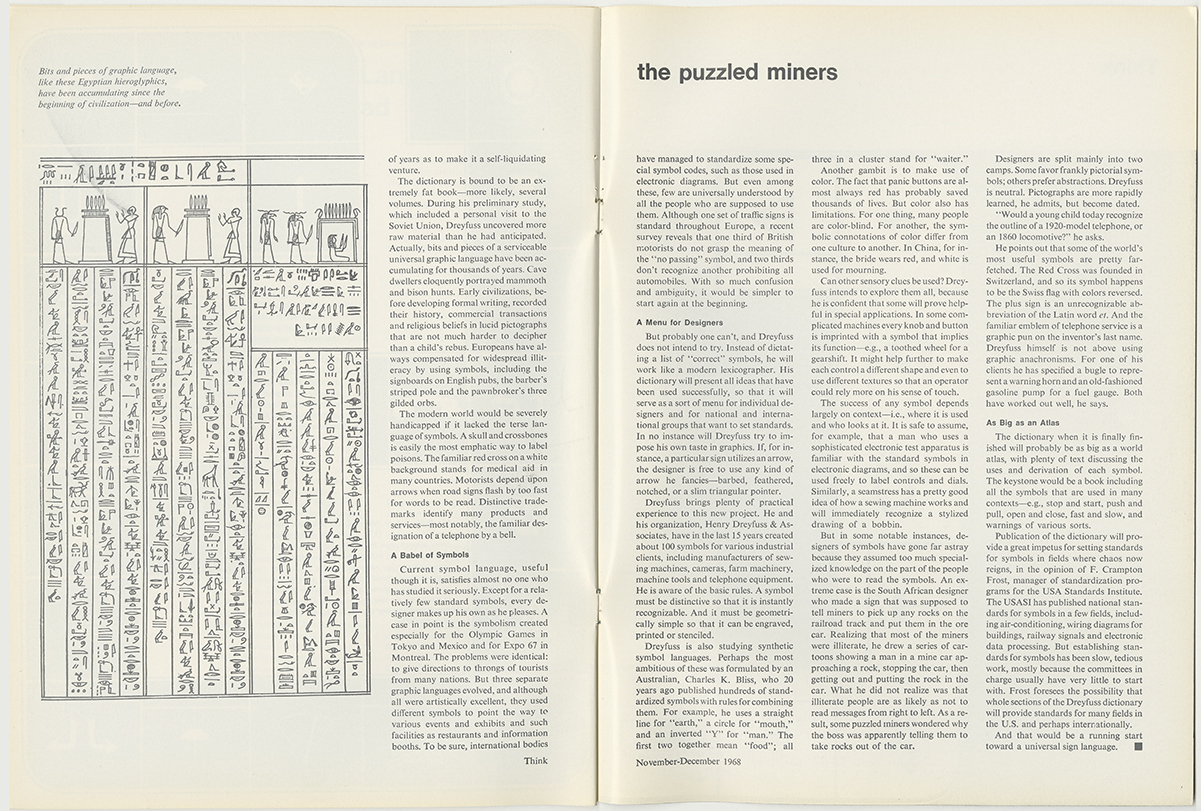

“A New Sign Language—Straight Ahead” by George A. W. Boehm, in THINK Magazine, November–December 1968 (Vol. 34, No. 6)

“Many a tourist has found himself losing something in translation—his way, usually—and the problem is far more serious for international airlines, highway officials, industries heavily involved in export-import. A universal sign language, many authorities believe, could go a long way toward coping with the babel of our society.” —George A. W. Boehm

This is the opening text for this article that features “A Game of Symbols” (Fig. 3), a diagram showing how easy it is to navigate using symbols. Dreyfuss knew Boehm well, and it is obvious that Boehm understood Dreyfuss’s motivations and ambitions for producing the Symbol Sourcebook.

Fig. 3: “A New Sign Language—Straight Ahead” by George A. W. Boehm, in THINK Magazine, November–December 1968 (Vol. 34, No. 6); Henry Dreyfuss Archive

The article describes the background for Dreyfuss’s work: “A worldwide crisis in comprehension bedevils public safety officials, managers of international airports, manufacturers of machinery, cartoonists, designers of posters, and others who want to make themselves instantly intelligible. They need a common language—one that will function as smoothly in everyday life as church Latin, diplomatic French, Morse code and mathematical notation have among specialists.” Or, to put it simply, a universal set of symbols that will say the same thing in any language.

Boehm’s understanding was that universal symbols could become a new lingua franca in a time when international trade was booming, air travel was becoming more accessible, and messages could be exchanged electronically in minutes (via cable). He predicted that international television “will soon fill the air with new ideas voiced in strange tongues.” This was the territory of Glyphs, Inc., and Boehm references their then-recent August 1968 article in Natural History: Glyphs are “a set of clear, unambiguous signs that can be understood by the speakers of any language, and by members of any culture, however primitive. These signs will enable mankind to use the great new freedom of worldwide travel. Without them hungry, frightened, confused people will continue to clog the travel lanes, come to grief on the roads, return disenchanted to their small provincial worlds, and contribute to the isolation and hostility in which many human communities live today.” This whole worldview chimes with Dreyfuss’s ideas on internationalism, but Boehm continues, “Now a somewhat more concrete proposal has stirred up excitement,” with pragmatism taking over from the utopianism of Mead and Modley.

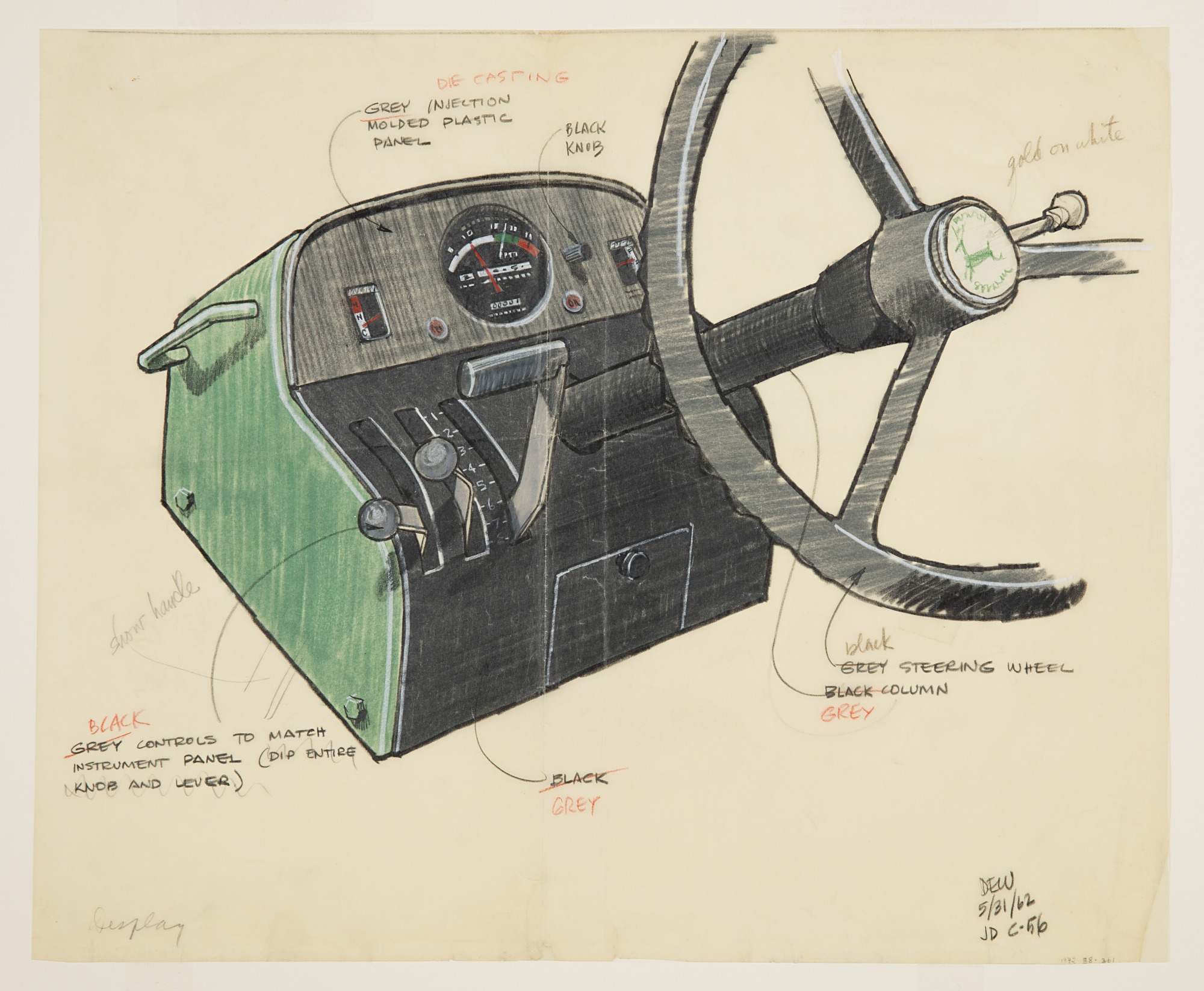

Boehm explained how Dreyfuss was uniquely equipped to take on this ambitious symbol project due to his experience designing symbols for industrial clients over the past 15 years (Fig. 4). Dreyfuss was aware of the rules of symbol design: they must be distinctive, instantly recognizable, and easily reproduced. Symbols must also work across several cultures and take account of how sensory clues (such as shape and texture) affect the audience’s response. The success of any symbol also depends largely on context—where it is used and who looks at it. Boehm explains that in some instances, symbol designers have assumed too much specialized knowledge on the part of the audience who cannot understand symbols, leading to confusion. He reports that symbol designers are split mainly into two camps: the pictorial and the abstract. Dreyfuss remains neutral.

Fig. 4: Drawing, Design for a Tractor Instrument Panel, May 31, 1962; Designed by Henry Dreyfuss Associates for John Deere (Moline, Illinois, USA); Color pencil and graphite on cream tracing paper; 35.3 × 42.8 cm (13 7/8 × 16 7/8 in.); Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-361

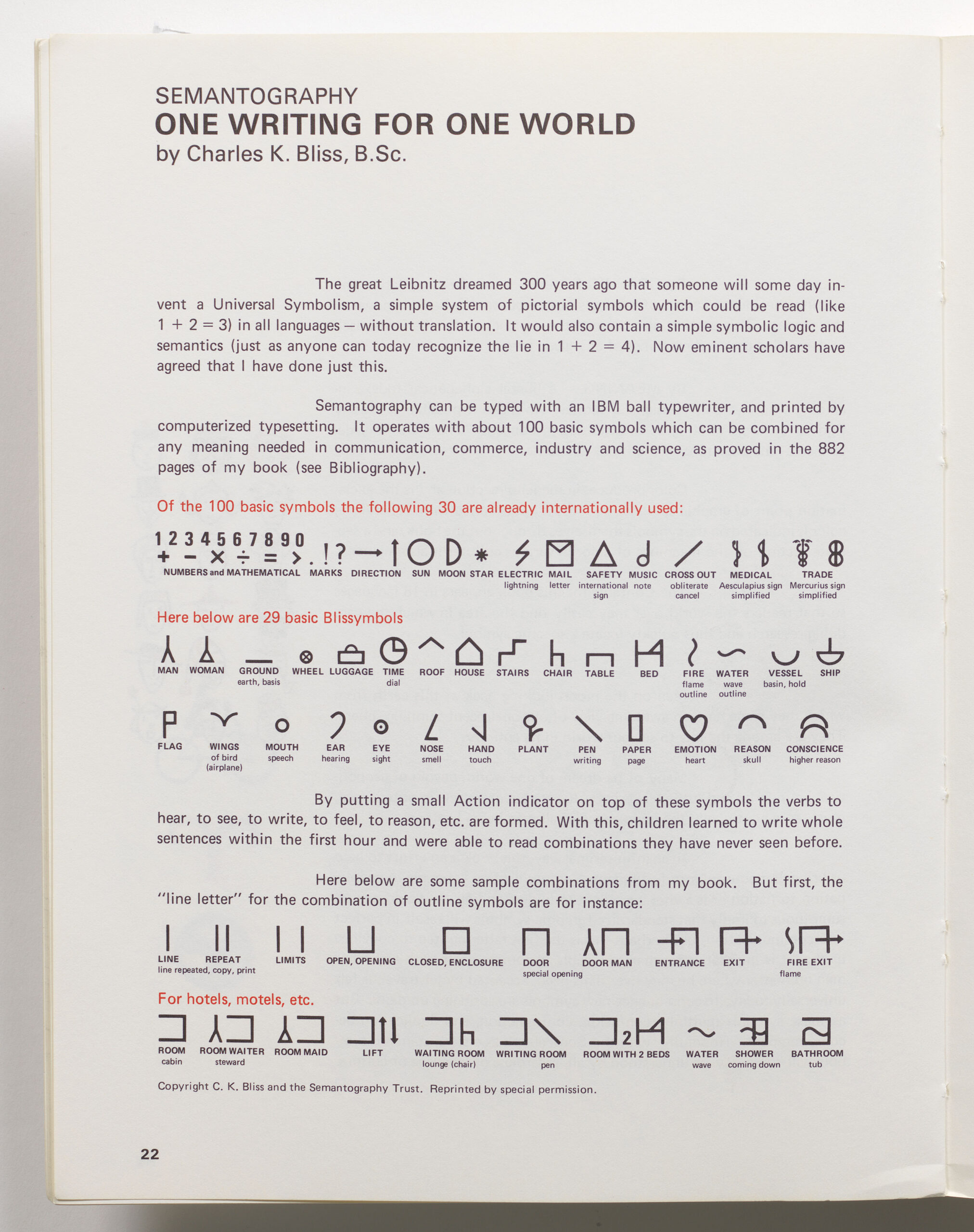

The article features an illustration of Egyptian hieroglyphics (Fig. 5). Boehm explains that Dreyfuss (after a trip to the Soviet Union) became interested in “bits and pieces of a serviceable universal graphic language that have been accumulating for thousands of years” before they developed into formal writing systems. Dreyfuss was also studying synthetic symbol languages, such as Charles K. Bliss “Bliss Symbols,” a language which consists of a set of hundreds of standardized symbols with rules for combining them (Fig. 6).[2]

Fig. 5: “A New Sign Language—Straight Ahead” by George A. W. Boehm, in THINK Magazine, November–December 1968 (Vol. 34, No. 6); Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 6: “Semantography: One Writing for One World” by Charles K. Bliss, in Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, 1972; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Finally, Boehm identifies the big problem with the lack of standardization in symbol design—“A babel of symbols”—and how often designers just create new symbols rather than developing or evolving existing ones. He points out that some symbols have been standardized, but relatively few are universally understood. He asks if, with so much confusion around, would it indeed be simpler to start again? Of course, this is impossible, and it was Dreyfuss’s intention to present symbols that have been used successfully in his book, creating a “menu for individual designers and for national and international groups that want to set standards.” Mr. F. Crampton Frost, manager of standardization programs for USASI, had published national standards for symbols in a few fields (including air-conditioning, wiring diagrams for buildings, railways signals, and electronic data processing), but it was a slow process. Frost saw great promise in Dreyfuss’s work in the establishment of US and international standards for symbols. And that, Boehm suggests, “would be a running start toward a universal sign language.”

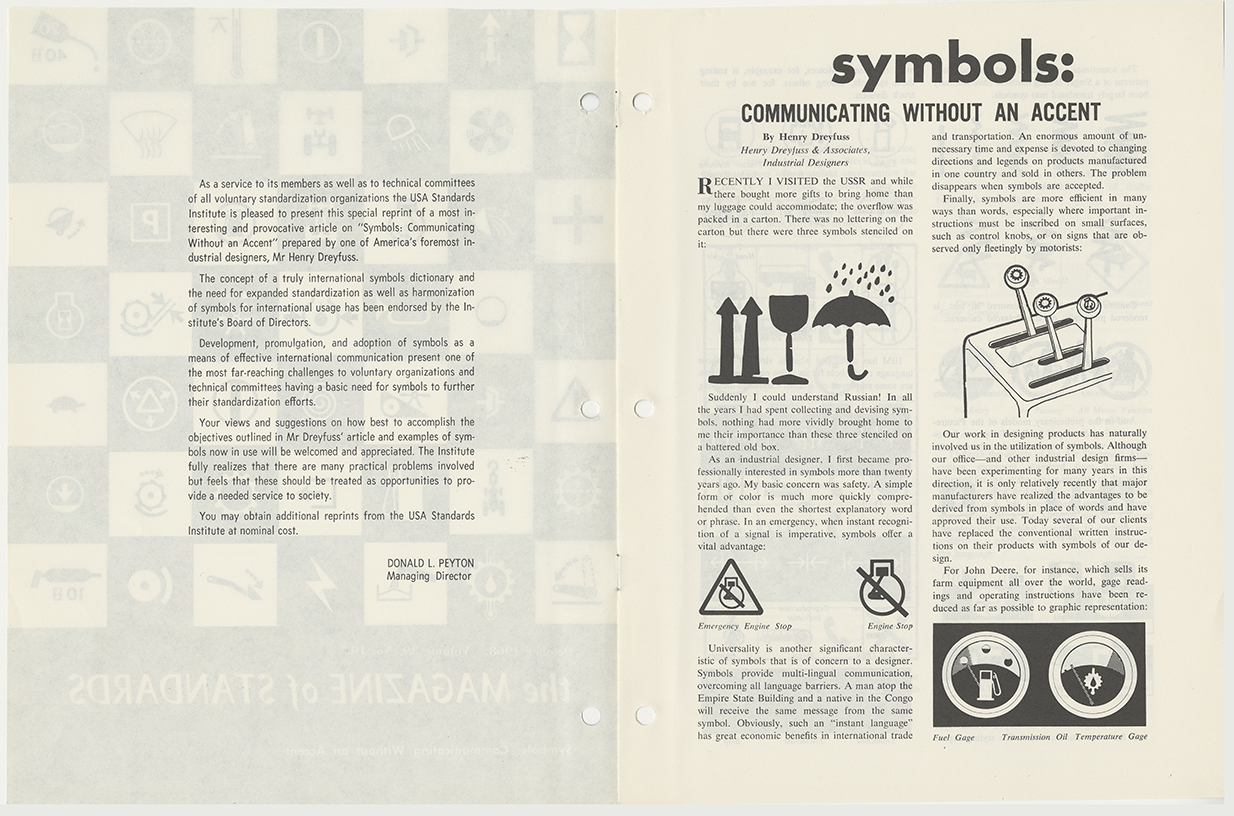

“Symbols: Communicating Without an Accent” by Henry Dreyfuss, in The Magazine of Standards, October 1968 (Vol. 39, No. 10)

The second printed article sent out with correspondence, “Symbols: Communicating Without an Accent,” was written in 1968 while Dreyfuss was still running Henry Dreyfuss & Associates. It is richly illustrated with examples of symbols and graphic languages (Fig. 7). It begins with a foreword by Donald L. Peyton, managing director of USASI,[3] who was enthusiastic about the need for standardization, but was aware of the practical problems involved and felt that they should be treated as “opportunities to provide a needed service to society.”

Fig. 7: “Symbols: Communicating Without an Accent” by Henry Dreyfuss, in The Magazine of Standards, October 1968 (Vol. 39, No. 10); Henry Dreyfuss Archive

“The concept of a truly international symbols dictionary and the need for expanded standardization as well as harmonization of symbols for international usage has been endorsed by the Institute’s Board of Directors. . . . Development, promulgation, and the adoption of symbols as a means of effective international communication present one of the most far-reaching challenges to voluntary organizations and technical committees having a basic need for symbols to further their standardization efforts.” —Donald L. Peyton

Dreyfuss begins his article with an anecdote about his inspirational trip to the USSR.[4] He reports that he sent gifts home to the US in a carton. When he received it back home, the symbols for “this way up,” “fragile,” and “keep dry” were stenciled on the carton. He exclaimed, “Suddenly I could understand Russian! In all the years I had been collecting and devising symbols, nothing had more vividly brought home to me their importance than these three stenciled on a battered old box.”

Dreyfuss’s most basic concern in symbol design was safety and how a symbol could provide immediate information when it is most needed. He explains his interest in universality, which designers need to be concerned about, and how symbols “provide multi-lingual communication, overcoming all language barriers.” He touches on the economic benefits for international trade and transportation that “instant language” can bring, and how well symbols can work on small levers for motorists. He reports that several of his clients have replaced written instructions with symbols to great effect, referencing his symbols for John Deere, Singer Sewing machines, and Polaroid Cameras, as well as the work that General Motors and IBM were doing in developing symbols for use by motorists and users of office equipment.

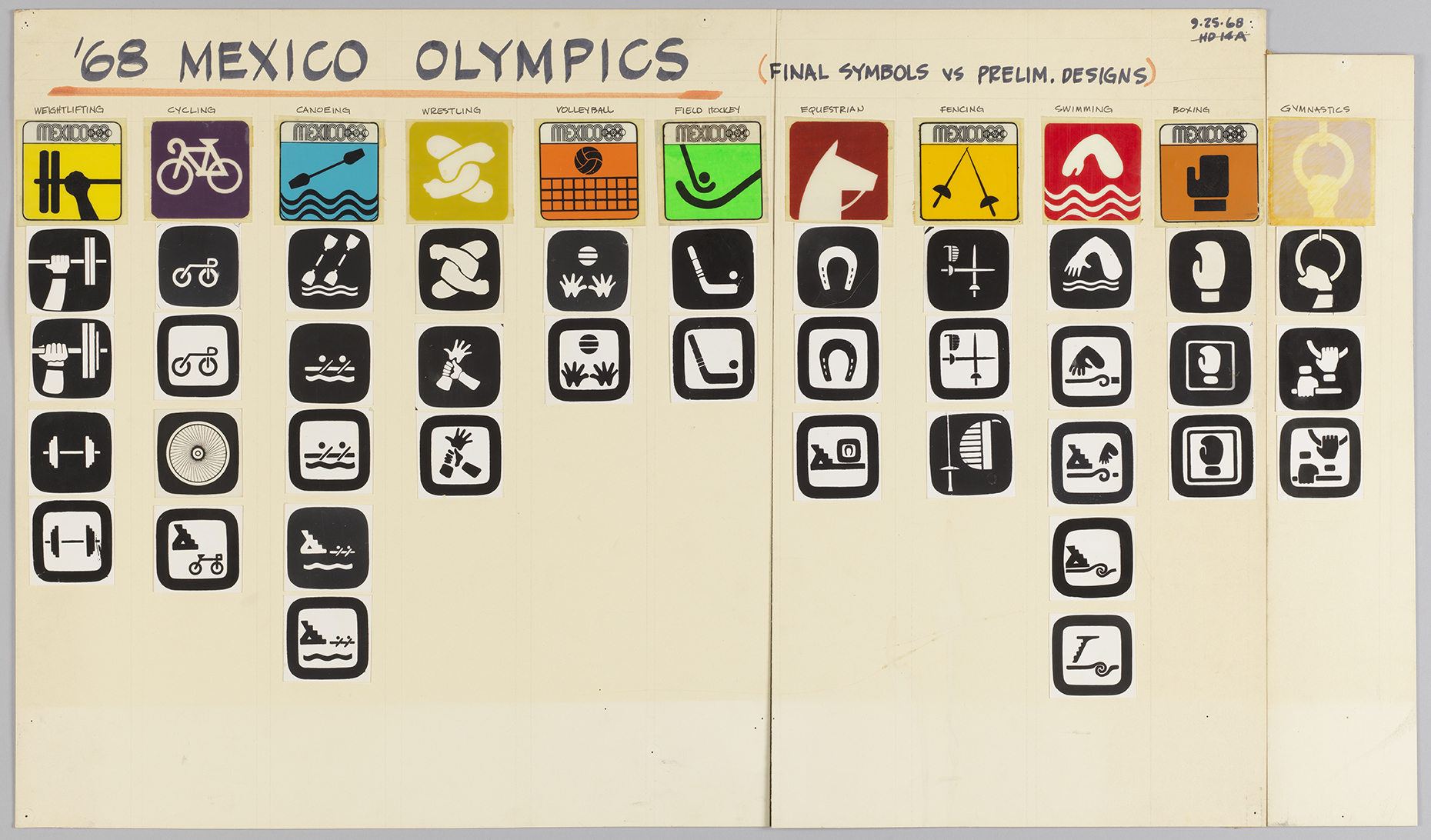

Dreyfuss then moves on to discuss directional symbols, quoting the examples of World Fairs and Olympic Games, which he notes, “provide interesting examples of how different designers approach the problem of abstracting the same concept in symbolic terms” (Fig. 8). He suggests that this is why standardization is needed, noting that if designers are going to “transcend the barriers of language, the same symbols need to be used in all countries.” He praises the Air Transport Association for the way that they have adopted symbol standardization in major international airports, which Dreyfuss used in the design of a new air terminal in Dallas, Texas. He observed the same symbols in the Moscow airport, so he was able to find his way around easily without understanding the Russian language. He quotes another example of good practice in the 21 member countries of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), who have adopted “a vocabulary of symbols designed for machine tool manufacturers.”

Fig. 8: Poster, ‘68 Mexico Olympics, Final Symbols vs Prelim. Designs, 1968; Designed by Henry Dreyfuss (American, 1904–1972); Ink and collage on posterboard, adhesive tape, glue; 49.8 × 85.4 cm (19 5/8 × 33 5/8 in.); Gift of Henry Dreyfuss, 1972-88-1-7-1,2

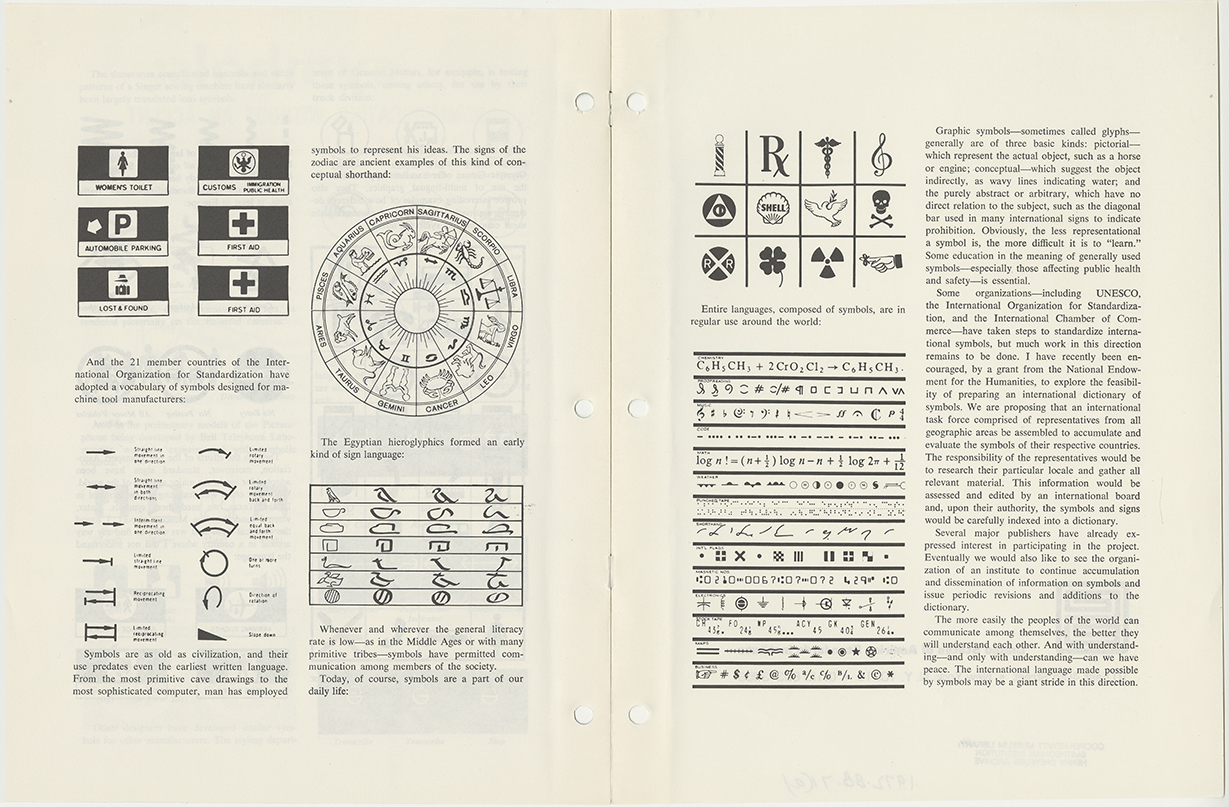

Dreyfuss also uses this article to discuss his interest in symbols from ancient civilizations: “From the most primitive cave drawings to the most sophisticated computer, man has employed symbols to represent his ideas.” He illustrates examples of zodiac signs, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and symbols from daily life (such as the barber’s pole, the treble clef, the Shell logo, and the skull and crossbones). He also shows examples of modern-day symbol language from chemistry to weather symbols, Morse code and electronics (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: “Symbols: Communicating Without an Accent” by Henry Dreyfuss, in The Magazine of Standards, October 1968 (Vol. 39, No. 10); Henry Dreyfuss Archive

As an article written to educate his audience on the importance of symbols in everyday life, he references glyphs (or graphic symbols) and describes the three basic types of symbols: pictorial (representing the actual object), conceptual (suggesting the object graphically, such as wavy lines for water), and abstract or arbitrary (having no direct relationship to the object, such as the diagonal bar to represent prohibition). He makes the point that the more abstract a symbol is, the more difficult it is to learn.

Dreyfuss finishes the article by providing good examples of how some organizations such as UNESCO, ISO, and the International Chamber of Commerce have begun to standardize symbols within their organizations, but suggests that much more work is needed in this direction. He uses these examples to introduce his “international dictionary of symbols” project. Like Boehm, he describes his ambitions for the project, the proposed international involvement from “representatives from all geographic areas,” and the interest of several publishers. His intention was for the information collected to be “assessed and edited by an international board and, upon their authority, the symbols and signs would be carefully indexed into a dictionary.” He sees the culmination of the project in the organization of an institute “to continue accumulation and dissemination of information on symbols and issue periodic revisions and additions to the dictionary.” He ends by stating, “The international language made possible by symbols may be a giant stride in this direction.”

These two articles set out Dreyfuss’s ambitions for his Symbol Data Bank and what would become three years later the Symbol Sourcebook. They are similar in content—with Boehm’s article being more text-heavy and Dreyfuss’s more illustrative—but the intention of both seen together, and sent with correspondence asking for detailed symbol information, must have strongly delivered the point that symbols were the way forward for international communication and that Dreyfuss (with the recipient’s help) was the one to make this happen. Reading these articles demonstrates Dreyfuss’s overwhelming determination to both make his project a reality, but also the pragmatism and adaptability required to turn the project into a workable proposition.

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Notes

[1] This is taken from Mead and Modley’s article: “Anyone can travel to anywhere on the planet in 36 hours, but people speak 2,800 languages, and it would be impossible to provide enough interpreters at airports to aid potential travellers . . . Glyphs are the only universal graphic communications device that is in the public use. Glyphs communicate visually. Their message provokes ‘visual thinking’ instead of ‘verbal thinking.’”

[2] Bliss symbols are featured in the Symbol Sourcebook. Dreyfuss corresponded with Bliss at length during the production of the book.

[3] Dreyfuss often consulted Peyton in symbol-related matters over the years, and correspondence is friendly and informal. Peyton provided Dreyfuss’s introduction to the International Standards Organization (ISO).

[4] A booklet was printed entitled “From Russia . . . with hope” based on Dreyfuss’s acceptance speech for the award of honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles County on May 17, 1968. Dreyfuss’s trip to Russia circa May 1968 showed him how small the world was becoming: “I had breakfast in Moscow, lunch in London—and in a slightly comatose state—attended a dinner party in New York. That day I really understood what people mean when they say the world is shrinking. I think I shrank a little myself.”

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.