Written by Dr. Sue Perks

In conjunction with the exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols, designer and researcher Sue Perks offers an expansive look into the Henry Dreyfuss Archive held at Cooper Hewitt. The archive contains detailed documentation on Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols, which serves as the basis for the exhibition.

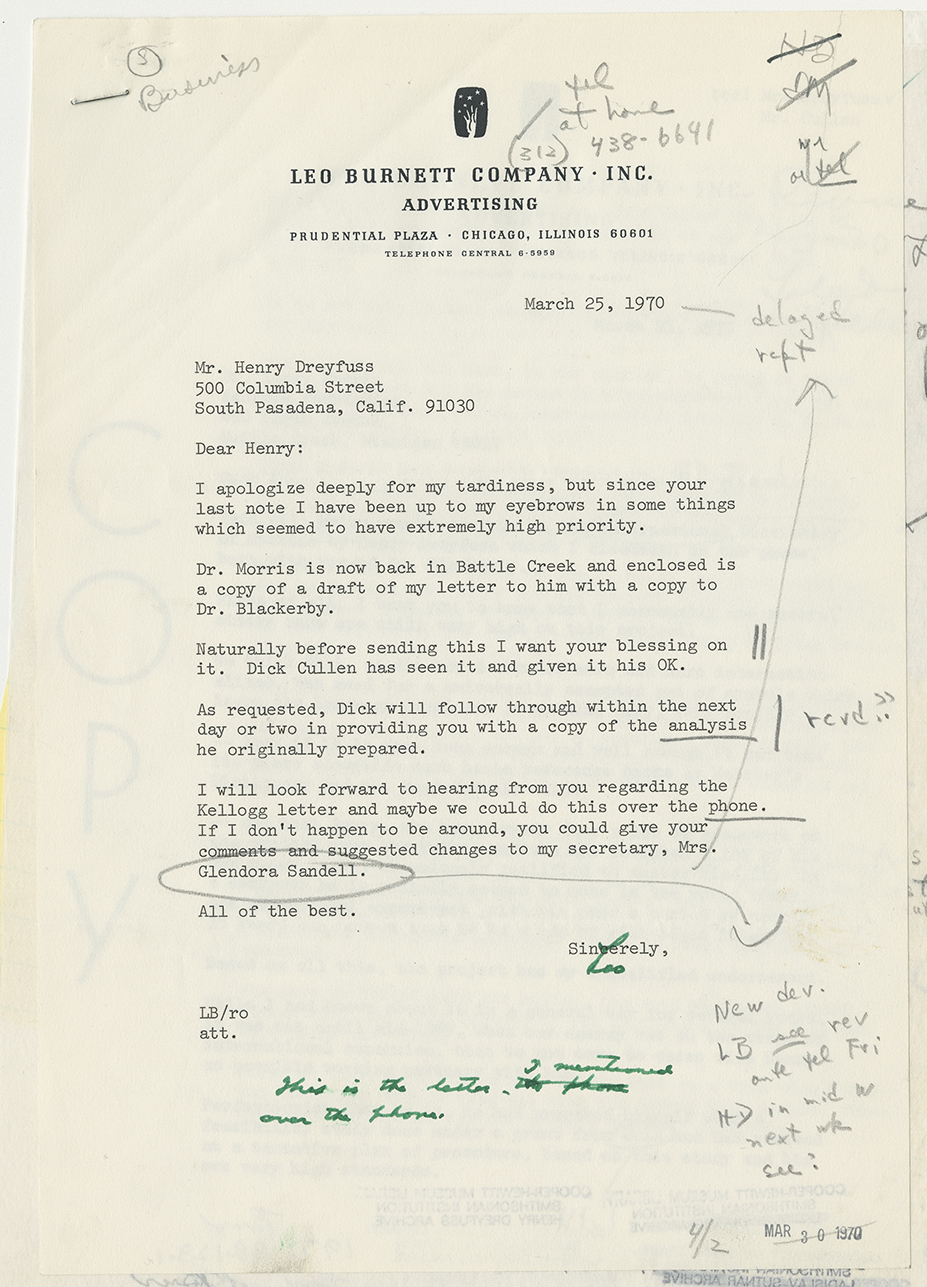

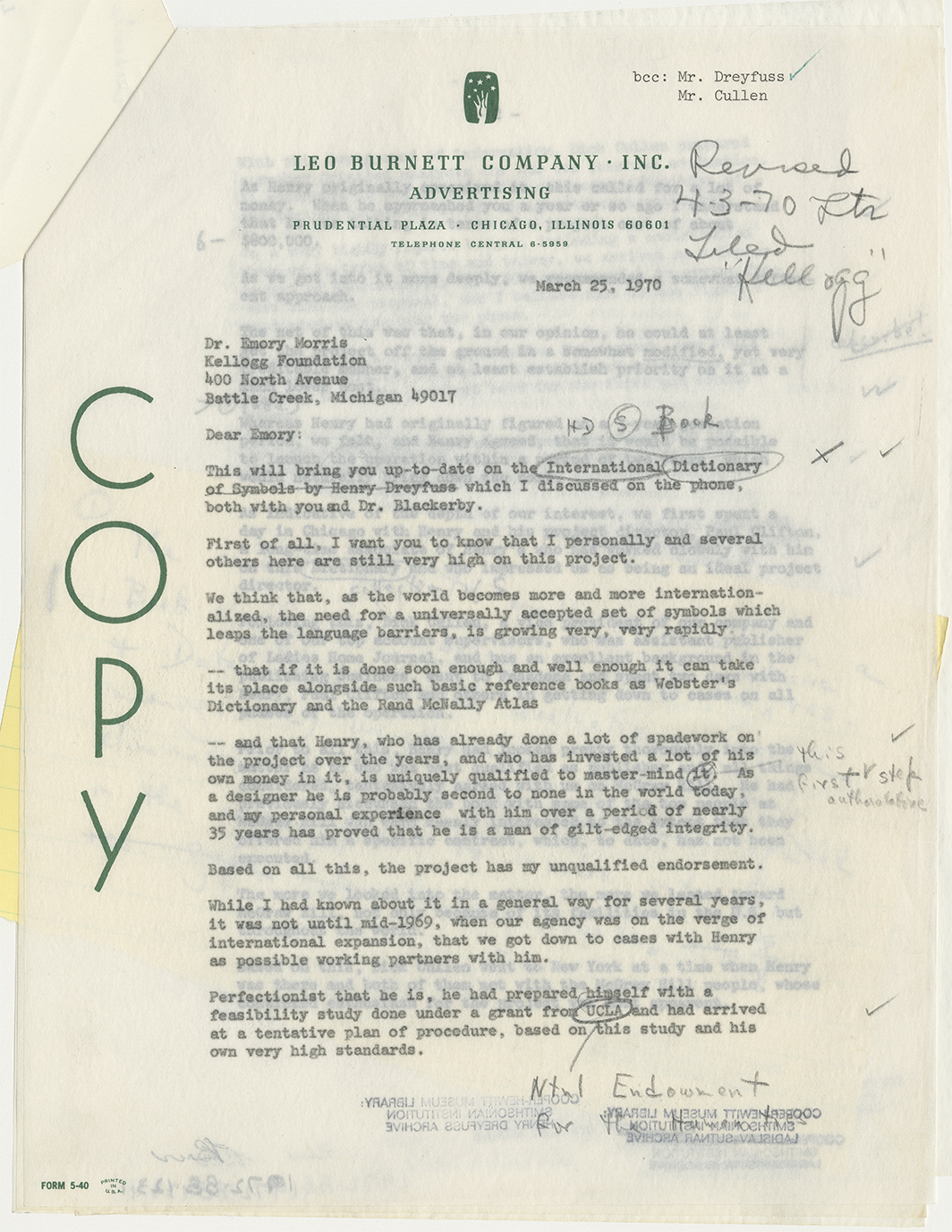

Leo Burnett (1891–1971), founder of the Chicago-based international advertising agency Leo Burnett Company Inc. (LBC), had a personal involvement with the Symbol Sourcebook and in 1970 Dreyfuss and Burnett considered becoming partners on the project. The Henry Dreyfuss Archive holds detailed correspondence exchanged between their offices from June 1969 to 1971, including a report by Dreyfuss’s project manager, Paul Clifton,[1] describing the status of the book in December 1969 and, in response, a detailed feasibility study compiled by LBC’s Richard (Dick) Cullen,[2] which provided three alternative plans to finance and produce it (Fig. 1). The archive also contains letters from Burnett endorsing the symbol project to the Kellogg Foundation, which was enthusiastic about providing the funding needed to complete what was to become the Symbol Sourcebook. The following account references these reports along with Dreyfuss’s reaction to it all. It also reveals the trust and mutual respect that existed between Dreyfuss and Burnett, two significant creative visionaries of 20th-century design.

Fig. 1: Letter, Leo Burnett to Henry Dreyfuss, March 25, 1970; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

In 1969, Dreyfuss stepped away from his industrial design company Henry Dreyfuss & Associates. This enabled him to concentrate on the symbol project, which he had earmarked for his retirement. In his report, Cullen notes Dreyfuss’s passion for the project, describing him as “an idealist and a perfectionist” to whom compromise did not come easily, but who was happy to roll up his sleeves and get the job done. Cullen also made the point that Dreyfuss was not the first to sense a need for such a dictionary, and although the concept was not new, “no one has really gotten very far with the project.”[3] Coincidentally, in 1967, Dreyfuss’s friend and business associate of 35 years Burnett had also “moved out of the eye of the hurricane” (as he put it in 1969) to devote a major part of his time to corporate communications and special creative projects involving “symbolism.” In response to a press release from June 1969, Burnett expressed interest in Dreyfuss’s new shift toward making what he was then calling his “International Symbol Dictionary” a reality. Burnett agreed that LBC would produce a feasibility study, the task falling to LBC project administrator Cullen who prepared a detailed study to carefully evaluate the best way forward.

One radical solution was for the symbol project to be produced at LBC offices in Chicago. In 1968, Dreyfuss received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to produce a study entitled “The Design of a Research Project to Determine the Nature and Feasibility of an International Dictionary of Symbols,” but Dreyfuss needed to secure funding to complete the project, and partnering with LBC could have provided the solution. In 1968, Dreyfuss had approached the Kellogg Foundation for $800,000 to fund a three-year project with a proposal for an 824-page book to accommodate 10,000 symbols, but Kellogg, although interested, found the sums involved excessive. McGraw-Hill, with their extensive international publishing facilities, were also keenly interested, and in 1969 offered Dreyfuss a contract to produce a 576-page book to accommodate 6,700 different symbols (this was not taken up).

Status of what was known as the “Symbol Compendium” in 1969

To allow Cullen to prepare a feasibility study for the symbol project, Clifton produced a comprehensive report (dated January 19, 1970) that stated the scope of the project as it stood in late 1969. He began by outlining the limitations of the project: it would be as complete and accurate as Dreyfuss’s research would allow, but could not possibly include every symbol that existed (the reason why the word “dictionary” should also be avoided). Clifton emphasized the fact that the material was based on Dreyfuss’s evaluation alone, and no other endorsement or authority was implied, although reference would be made to the original source of all material, where available, and additional references would carry their own authority. It is worth noting that even before the project had achieved funding Dreyfuss was anticipating future editions to update and expand material for both the book and his Symbol Data Bank.

Physical Description and Content of the Book

The proposed book was to measure 8.5-by-11 inches, contain 824 pages, and include 10,800 symbols. It would be printed in 2 colors (black and red) throughout with full-color signatures (groups of pages in a book that are printed, bound together, and cut) where necessary. Symbol illustrations would be drawn “free hand” and all text would be in English.[4] Dreyfuss envisaged a foreword written by “an outstanding layman” followed by a preface by himself and/or another “informed person.” The preliminary section would include background features on the history and significance of symbols and “position papers” by contributing authorities (which would become Charles K. Bliss on Semantography and Marie Neurath on Isotype).

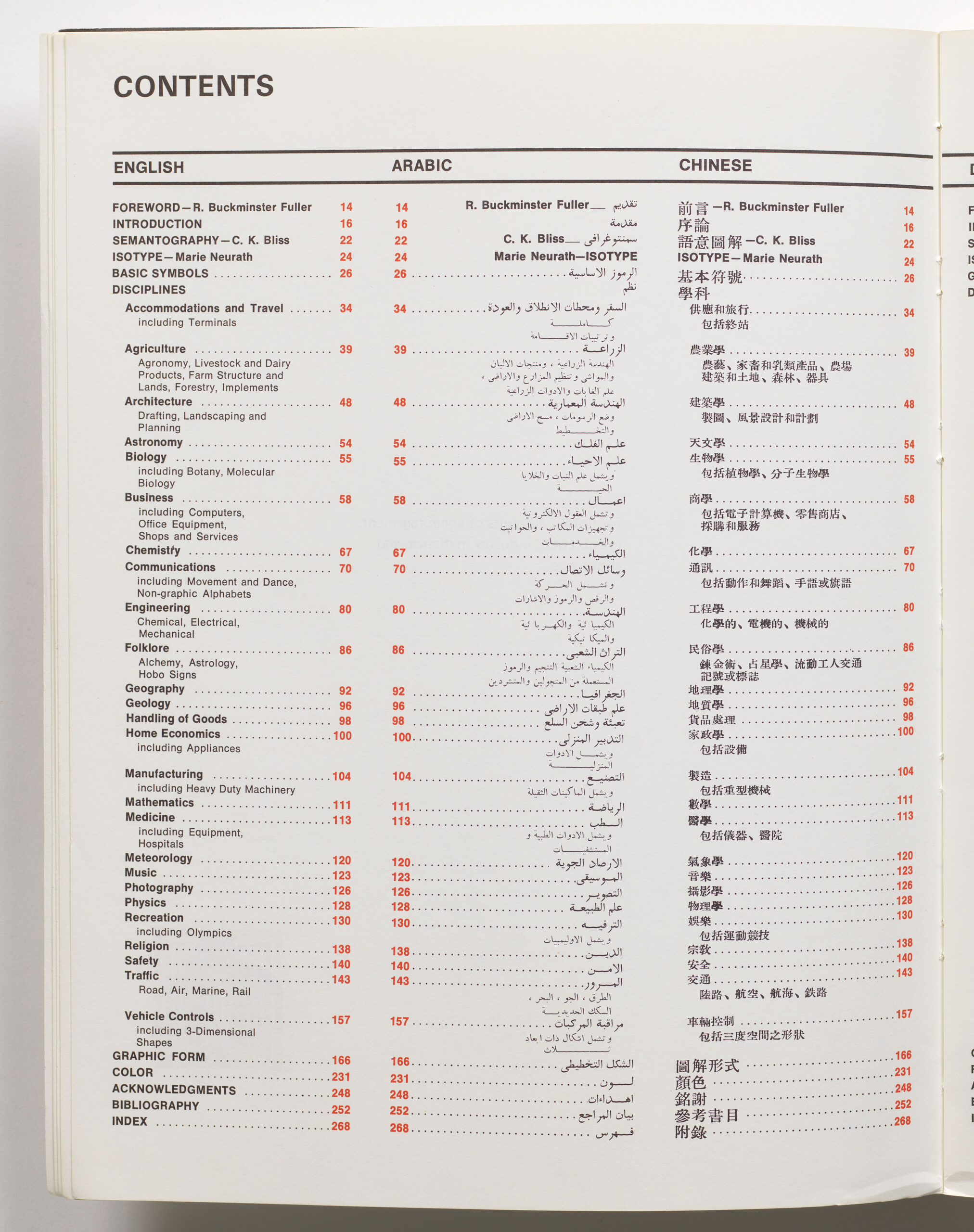

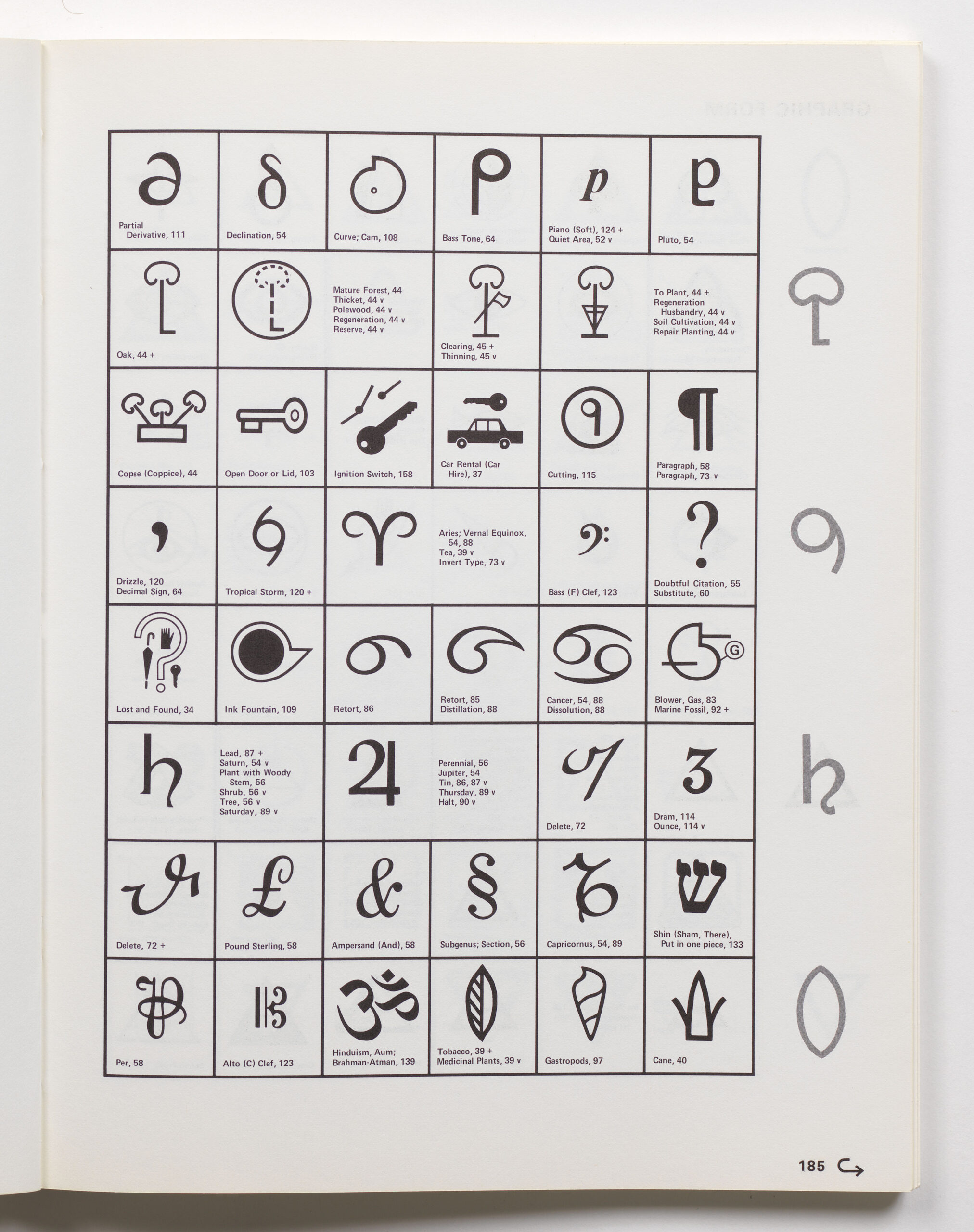

In 1969, the structure of the symbol content was complex and needed simplification, but the intention of creating a comprehensive cross-referencing system was firmly established. There were originally 38 Discipline sections (edited down to 26—see Fig. 2). Symbols were set on standardized grids and recognized authorities were contacted to assist in selecting the symbols. The “Graphic Form” section would provide reference to determine the meaning and area of application of a symbol and be divided into 3 sub-sections: “Geometrical” (circles, triangles, and lines), “Pictorial” (people, animals, and objects), and “Conventional” (letters and arrows). The “Graphic Form” section would include only those symbols illustrated within the book, and any one symbol could appear under more than one section (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Table of Contents, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 3: Graphic Form Section, Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Clifton’s 1969 report to Cullen included a design dummy, one of many produced, used as a working guide for the artwork and production. The report was designed to give Cullen the background knowledge he needed to fully understand the internal workings of the project, scrutinize the aims and objectives, and find the best way forward to make it happen. Cullen also set up meetings between Burnett personnel and Dreyfuss and spent time with Dreyfuss, his staff in South Pasadena, Califorina, and publisher McGraw-Hill in New York in December 1969. It is interesting to compare proposals for the book design from late 1969 with what was eventually published on January 12, 1972, just over two years later.

Cullen’s Report on “The Henry Dreyfuss Symbol project”[5]

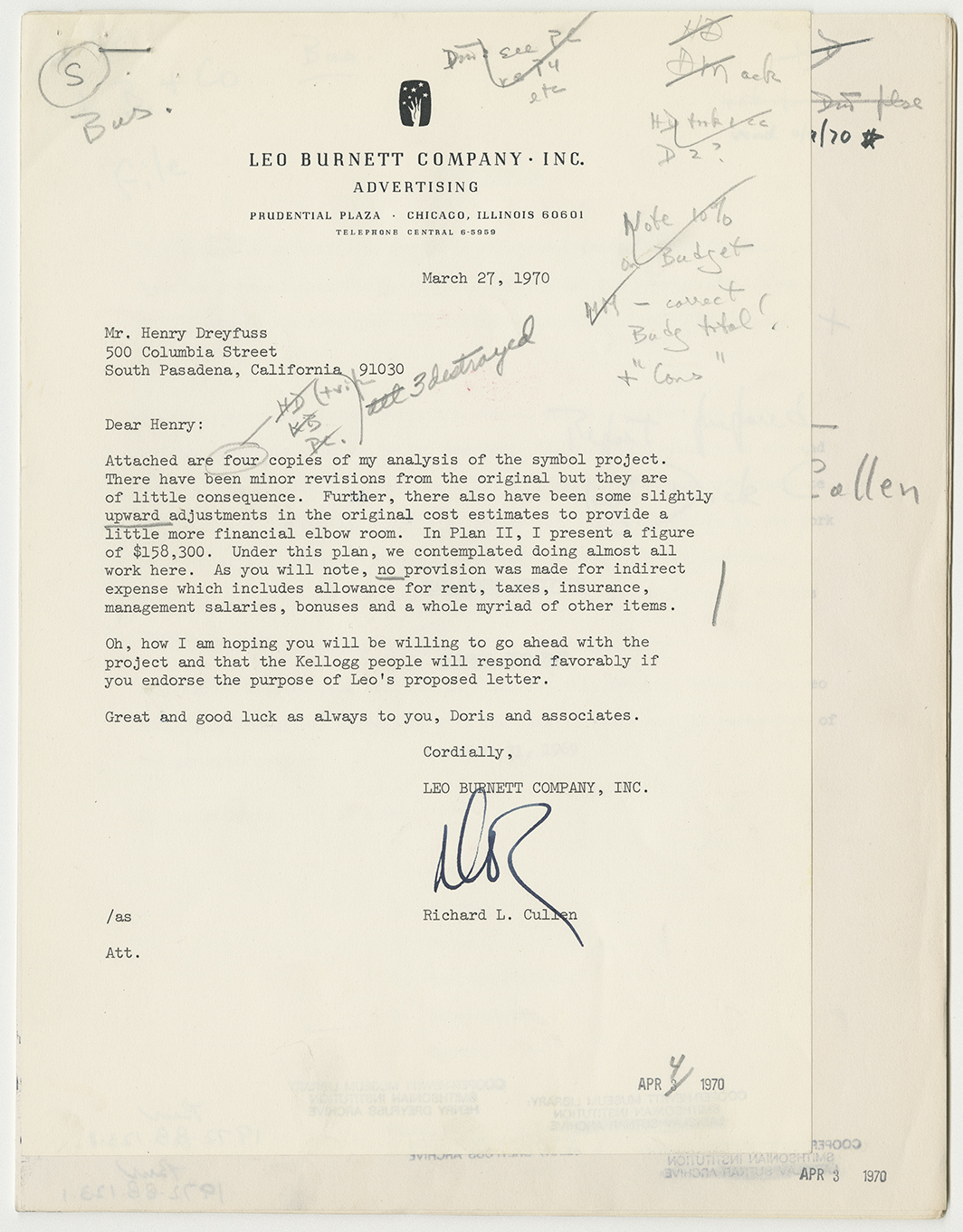

On March 27, 1970, Cullen responded to Clifton’s work by submitting a report to Dreyfuss that analyzed the feasibility of the symbol project and how LBC could participate in the development of what Cullen was now calling the “International Dictionary of Symbols” (Fig. 4). The report weighed the pros and cons of how, where, and who should produce the project, providing many insights into the internal workings of both Dreyfuss’s and LBC’s administration. Cullen had gathered numerous documents to enable staff at LBC to become fully acquainted with the project and how it would affect operations if production were to pass from Dreyfuss’s Pasadena office to LBC’s Chicago headquarters. Cullen’s report summed up the status of the project succinctly; his observations focused on finance and logistics, but also covered background, objectives, roles, responsibilities, and, crucially, three possible plans to produce it. Cullen, along with Burnett and LBC management, were very enthusiastic that the project should go ahead, and Burnett personally wrote to the Kellogg Foundation to endorse it.

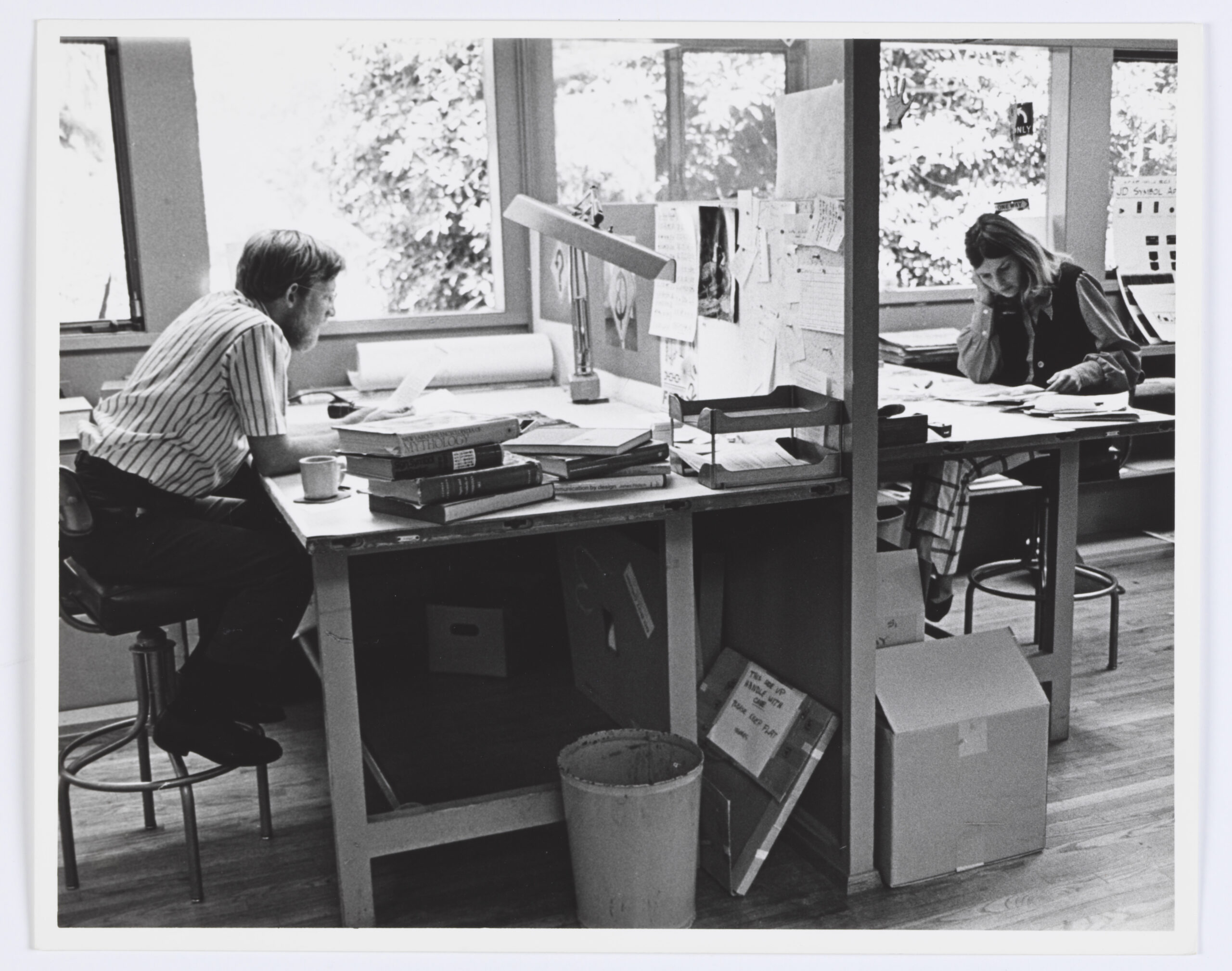

Cullen included a description of Dreyfuss’s office in South Pasadena and the staffing arrangements (Fig. 5). Much of the office space was not being used since Dreyfuss dissolved his industrial design business, but overheads were covered by Dreyfuss’s consultancy fees for companies such as ATT and American Airlines. Up until 1969, the symbol project had only involved the part-time effort of Clifton and Dreyfuss with secretarial support, but Cullen noted that if it were not for the “potentialities” of the symbol project, arrangements with Clifton would probably need to be terminated, and his continued involvement was crucial to the success of the project.[6]

Fig. 4: Letter, Richard L. Cullen to Henry Dreyfuss, March 27, 1970; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Fig. 5: Office of Henry Dreyfuss, South Pasadena, California, circa 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Progress to Date

By 1970, Dreyfuss had collected 20,000 symbols in his Symbol Data bank—15,000 in books and 5,000 from other sources (Fig. 6). He considered that 5,000 were useable in the dictionary, but a further 5,000+ would be needed to complete the proposed 824-page book.[7] Cullen was aware of the huge amount of correspondence generated in the hunt for the most appropriate symbols,[8] and this detailed process was by far the most time-consuming part of the operation.[9] Cullen evaluated McGraw-Hill’s 1969 contract for a 576-page book and considered that they would be the ideal project partner, noting their enthusiasm, even though they did not initially foresee any real opportunity for profit. However, McGraw-Hill was quick to realize that if the dictionary gained widespread acceptance and was revised and extended over the next 10 to 20 years, then a profit might be made. Initial estimates put a price on the volume of $29.50 with predicted sales of between $18 and 25 million for the first edition in the first year.

Fig. 6: Fencing Symbol of the Meadowbrook Sports Centre, Edinburgh, Scotland; Designed by Columbus Dixon Co.; July 23, 1970; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Objectives

There were three main objectives for the project, which surprisingly didn’t include making a profit! Cullen considered it desirable to make them clear, so all parties were in agreement:

- Publish a high-quality dictionary of international symbols primarily for industry, governmental, and institutional use.

- Gain worldwide acceptance for the dictionary and eventually its adoption as the international standard.

- Recover “out of pocket” expenses.

Cullen’s three alternative plans

Cullen identified three alternative plans to complete the program, carefully considering pros and cons for each, conducted over two years to cut costs[10]:

Plan 1: Program administered by LBC with development carried out by Dreyfuss’s office.

Plan 2: The entire program administered and developed by LBC in Chicago.

Plan 3: Adoption of either Plan 1 or Plan 2 but establishing a non-profit organization to solicit

outside financing.

Plan 1: Program administered by LBC with development carried out by Dreyfuss’s in Pasadena

The project would be continuously supervised by Dreyfuss in Pasadena—an asset unobtainable to the same degree if the project headquarters were elsewhere. Clifton’s role as project director would be paramount to the success of Plan 1.[11] The cost of this plan over two years would be $357,200.[12]

Plan 2: The entire project administered and developed by LBC in Chicago

In Cullen’s opinion, this would be the best way to get the job done efficiently with savings in out-of-pocket expenses. Secretarial help and art requirements would be completed primarily by LBC personnel, fitting the work into their existing LBC workloads.[13] A project director would either need to be sourced from present LBC staff or Clifton would need to be persuaded to move to Chicago (which he was reluctant to do). Another disadvantage would be the loss of regular consultation with Dreyfuss, as under this plan LBC would assume the real responsibility for the quality of the product. The cost of this plan over two years would be $243,300.[14] On paper, this was a much more economical option.

Plan 3: Adoption of either Plan 1 or Plan 2 but establishing a non-profit organization to solicit outside financing

If the project was generously funded by an outside organization, the dictionary could be more ambitious. The roles of project developer and project administrator could be funded and out-of-pocket costs and compensation for time and services recovered. If this plan was adopted, there was no reason why the project should not be developed and administered by Dreyfuss and those he would hire to get work done, with LBC out of the picture. The downside to this was that Dreyfuss had achieved no success with fundraising, vowing he wouldn’t do it again, but he would be agreeable if someone were to become his emissary. However, Cullen considers that Dreyfuss, like it or not, would need to be the one to attract support from an outside foundation, rather than one consisting of a non-profit organization made up of Dreyfuss, LBC, and McGraw-Hill.[15]

Cullen’s overview

The first move would be to approach organizations or institutions where LBC had strong relationships to provide financial support (Plan 3). If this was not practical, then it would be necessary to examine the merits of Plans 1 and 2. Cullen considered that Plan 2 was the most promising as it involved better control and less out-of-pocket expenses. LBC’s involvement could enrich their corporate image by association with an extremely worthwhile project, but Cullen was concerned whether LBC would be willing to accept the risk and responsibility for the development and administration of the project.

On April 6, 1970, Dreyfuss and Doris Marks wrote to Cullen saying that they were overwhelmed by the thorough and detailed thinking within the report, but not wholly convinced of its success. But their commitment to the project remained intact: “Just off the record our decision is that we will proceed willy-nilly. If this means pulling the dollars out of our own pockets, as will probably be the case, it is going to be quite a drain, but will still allow us to save a drink, or a sandwich, or a cup of coffee, for you at any time you get to this area. Let’s not let the symbol book keep us from getting together with you one of these days, either here or in New York.”

The Kellogg Foundation

Meanwhile in April 1970, Burnett, in close consultation with Marks, was writing a draft letter to the Kellogg Foundation with an aim to seek funding for the project (Plan 3). The archive also contains a personal letter from Burnett to Emory Morris of Kellogg (cc’d to Dreyfuss) dated March 25, 1970, that explains the reasons why Kellogg should support the “International Dictionary of Symbols” (Fig. 7). Burnett was under the assumption that the symbol project would fit within the overall policy and objectives of the Kellogg Foundation. He begins by explaining, “as the world becomes more and more internationalized, the need for a universally accepted set of symbols which leaps the language barriers is growing very, very rapidly . . . if it is done soon enough and well enough it can take its place alongside such basic references as Webster’s Dictionary and the Rand McNally Atlas.” Burnett describes Dreyfuss’s long-term commitment to the symbol project and how he had invested a great deal of his own money in it and that Dreyfuss was uniquely qualified to mastermind the project as a designer who was “probably second to none in the world today, and my personal experience with him over a period of nearly 35 years has proved that he is a man of gilt-edged integrity.”

Fig. 7: Letter, Leo Burnett to Emory Morris, March 25, 1970; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

The letter has a poignant ending regarding Burnett’s personal participation in the project: he was 79, his health was failing, and he needed to consider his future priorities.[16] Cullen was in favor of taking the production of the book to LBC’s Chicago offices (Plan 2), but Burnett considers that the project should stay with Dreyfuss in Pasadena (Plan 1) with “Henry remaining as the guiding spirit” under the management of Clifton (who was not interested in relocating to Chicago). The letter continues by stating that the visible association of an advertising agency with a project of this character may give it “undesirable commercial overtones which would not be true of a well-regarded Foundation such as Kellogg.” Burnett ends by withdrawing from any active participation or responsibility for the project but endorsing the fact that Kellogg, with all its worldwide interests, could derive a great deal of satisfaction and pride from being involved with it.

On the back of Burnett’s endorsement of the project, in mid-April 1970, Dreyfuss met with the Kellogg Foundation at their headquarters in Battle Creek, Michigan. They appeared willing to consider a grant of $300,000 over two years to help launch the project.[17] But working with Kellogg was not straightforward, and the grant proposal would need to be is presented through a degree-giving university and UCLA was suggested (where Dreyfuss had been on the staff). There were also other issues regarding royalties and overheads.[18] However, these appeared to be minor problems that could be ironed out and Burnett’s championing of the project had considerably helped to create a good impression with Kellogg. But on May 14, 1970, Dreyfuss’s misgivings about working with Kellogg forced him to write to Burnett, “the result of much, much soul searching,” informing him that he had made the decision to not go ahead with Kellogg. The final straw being Dreyfuss’s objection to Kellogg’s non-profit fund to distribute royalties. He wrote to Burnett “Doris and I decided that my nature is such that I had better go ahead and work independently.” Dreyfuss was confident that the McGraw-Hill contract would be signed during the following week and the project was moving full steam ahead. He made it clear how grateful he was for all of LBC’s interest, time, and effort. Kellogg were informed of his decision at the same time.

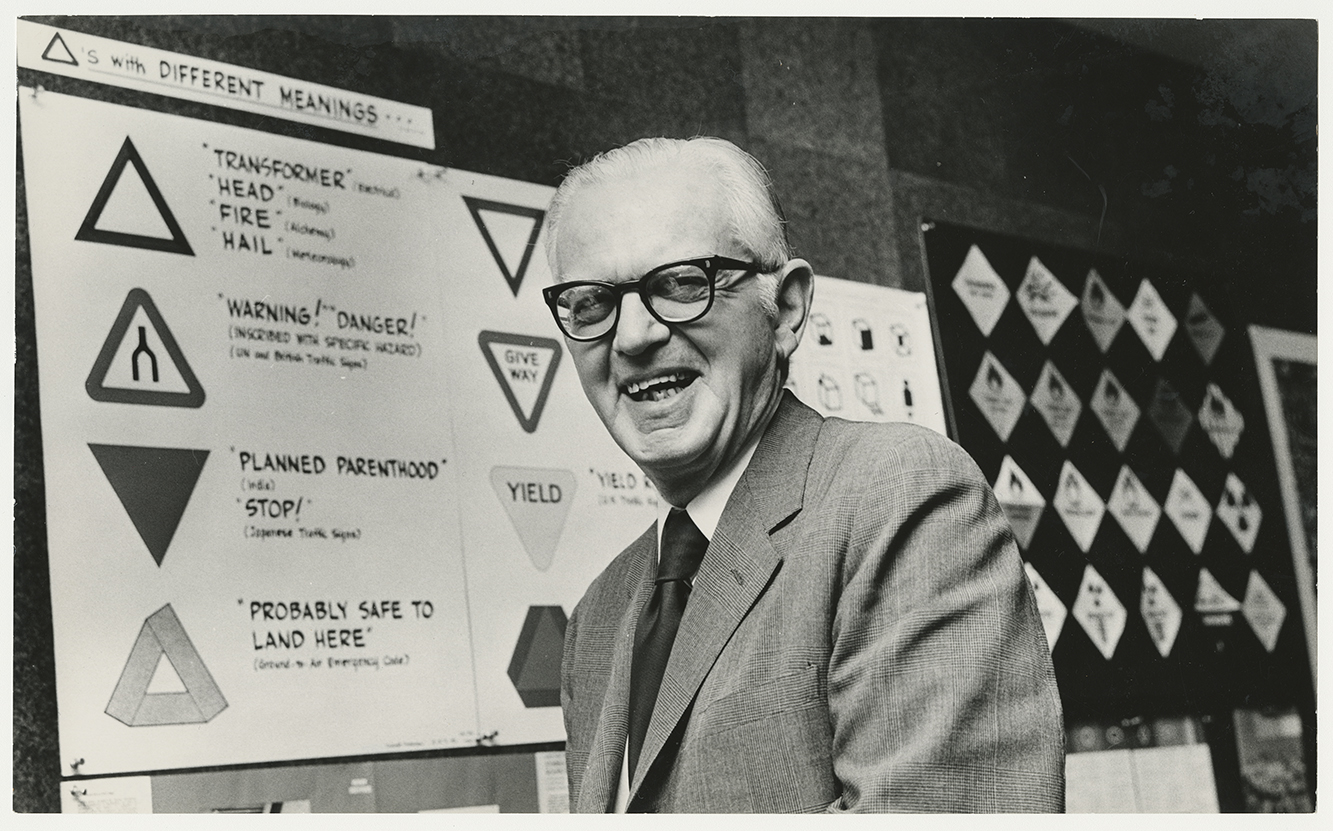

Consequently, the Symbol Sourcebook was designed in Dreyfuss’s Pasadena offices where a small loyal team was recruited to complete the project, funded by himself in under two years (Fig. 8). He believed that Kellogg would have given them the grant but was not prepared to work with the restrictions they imposed. On July 28, 1970, he wrote to Burnett with the good news: “We’re in business! We have signed a contract with McGraw-Hill to proceed with what we now call THE HENRY DREYFUSS SOURCEBOOK OF SYMBOLS, and I wanted you to be the first to know. By mid-1972 I hope we will see a book on the market. Thank you for believing in a dream which will now become a reality.” Sadly, Burnett did not live to see the publishing of the book (he died on June 14, 1971), but, writing to Cullen on November 3, 1971, Dreyfuss reflects on Burnett’s interest in the symbol project and how he wished he could have shown him the book (published on January 11, 1972). In the same letter to Cullen, Dreyfuss wrote, “I really don’t know what I have given birth to, but it has been a horrendous job. Now that it is finished, I am anxious to see it used. Actually, my interest in symbols goes far beyond selling a book. One thing I feel confident about is that this volume will be a good instrument to encourage people to use symbols.”

Fig. 8: Henry Dreyfuss with Triangle Comparisons, 1971; Henry Dreyfuss Archive

Dr. Sue Perks is a designer, archival researcher, and writer on Isotype, museum design, and Henry Dreyfuss’s work with symbols. She was awarded a PhD from University of Reading in 2013. She regularly presents at international design conferences and co-founded The Symbol Group in 2022.

The exhibition Give Me a Sign: The Language of Symbols is on display at Cooper Hewitt through September 2, 2024.

Notes

[1] Paul Clifton studied at UCLA where Dreyfuss had academic associations. He had been employed by Dreyfuss since the mid 1960s.

[2] LBC vice president and project administrator Richard (Dick) Cullen of LBC had a prestigious background in publishing that made him the ideal person to undertake this feasibility study.

[3] Previous attempts at symbol dictionaries had been proposed in the 1930s by Lasswell and Modley (to the Carnegie Corporation), in 1956 by Modley (to Dreyfuss), in 1959 by Modley (to the Fund for the Advancement of Education), and in 1963 by Weisman and Modley (to the National Science Foundation). None had reached fruition.

[4] The final contents section appears in 18 different languages, obviously adding to Dreyfuss’s international intentions for the book.

[5] The Symbol Sourcebook is referred to using several different names throughout this article, but the author uses the term “symbol project” as a generic title, even though the words “dictionary” and “compendium” are used by others when describing the project.

[6] Cullen notes that while Dreyfuss appears to be very comfortable financially, he does not feel that he can justify absorbing the cost of the symbol project without outside help. Marks estimated that they had invested nearly $300,000 of their own money in the project, but that included Dreyfuss’s time at full commercial scale.

[7] The completed Symbol Sourcebook contains 292 pages.

[8] Cullen describes how Clifton initiated a substantial amount of correspondence relating to the logical sources of symbols and received replies from about 35 percent. When there was no response, a follow-up mailing generated an additional 15 percent return. However, it was noted that not all replies provided symbols and some just supplied fresh leads.

[9] Cullen suggested the idea of measuring “time per symbol” as a way of costing it out. 10,800 symbols would need to be processed for publication. 5,000 had been collected by Dreyfuss, leaving a further 5,800 to be sourced. Symbols were received on average of 10 at a time. Half of receipts would be useable, so the other half would need only partial handling.

[10] Dreyfuss originally proposed completing the project in three years.

[11] Cullen noted that Doris Marks had “no appetite to handle the work in Pasadena” (which could be attributed to her failing health). From a financial perspective, Cullen considered that Dreyfuss was looking to LBC for financial relief, and it was not clear who paid for what.

[12] Consisting of $153,800 out-of-pocket costs and $203,400 of LBC’s administrative time. These sums did not include overheads for the Pasadena office (light, heat, taxes, maintenance, etc.). Cullen estimated 3 hours a week for 26 weeks for Dreyfuss and his staff to collect symbols using LBC staff in their 26 offices, with secretarial translation when needed.

[13] While a lower “out of pocket” cost would be attractive, this substantial project would require taking LBC staff away from servicing their client base, and a project of this size could not easily be slotted into existing schedules.

[14] Consisting of $85,000 of out-of-pocket expenses and $158,300 of LBC’s administrative time. This did not include provision for indirect expenses (allowance for rent, taxes, insurance, management salaries, bonuses, and a whole myriad of other items).

[15] It is possible that McGraw-Hill would not be involved in the non-profit structure and would only fill the role of a supplier.

[16] Burnett also wrote a heartfelt personal letter to Dreyfuss at this time regarding his “agonizing decision” to withdraw from the project, stating, “If we were to become project partners and our agency assume any major part of responsibility it would have to involve someone to pass judgement on problems which would arise—this involves many intangibles. My experience, over the last 35 years or so in helping launch quite a few ships in the public service arena, tells me that such a guiding spirit is essential to the happy realization of the original dream, and you can’t place a price tag on that.”

[17] Kellogg was appreciative of the reduced sum (Dreyfuss had originally requested $800,000 over three years): “Your letter and the dollar reduction in the grant request produced a very pleasant climate for the session.”

[18] Kellogg did not think that Dreyfuss should take royalties because the grant would take care of this. In addition, it would not pay overheads and Dreyfuss would not be compensated for his time.

Acknowledgments

Some funding contributed by the Design History Society Research Publication Grant.