In 2021, Cooper Hewitt’s department of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design launched a research and cataloging project to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the acquisition of the Jean Léon Decloux collection of ornament and architecture prints. This is the premier collection of ornament prints in the United States, consisting of over 430 bound albums containing some 13,000 European prints from the 16th through 19th centuries, with a particular strength in 18th-century French works. The project has led to the digitization of most of the collection and the cataloging of over 5,000 prints so far, which are now available online.[1] This is the first of a series of blog posts that will introduce the collection and explore some of the many treasures bound within.

BUT FIRST, WHAT IS AN ORNAMENT PRINT? AND WHY WERE THEY COLLECTED?

Ornament or ornamental prints were produced in Europe from the mid-15th to the 19th century, with the purpose of illustrating designs, patterns, or motifs of decorative ornament for use by craftsman and applicable to all aspects of applied arts from ceramic vases to furniture, from wall paneling to wrought-iron gates. They were usually published in small sets of four, six, ten, or twelve prints, sometimes referred to as pattern books.[2] They appealed to and were often marketed to both print collectors and artists or artisans alike, depending on the quality and finish of the designs and engravings. Ornament prints were both useful artistic models and works of art in and of themselves. These prints were produced by several artists and craftsmen, including the initial designers or architects whose creations were then interpreted and engraved onto metal plates by printmakers, which are in turn printed and published by print sellers and publishers. The Decloux collection represents one of the most important collections of its kind and illustrates the breadth and variety of the genre. They teach us firsthand about changes in style, approaches to design, evolving technologies of production, the activities of the art market, and networks of patrons, artists, designers, architects, printmakers, and publishers.

WHO IS DECLOUX AND WHY IS THE COLLECTION NAMED AFTER HIM?

Fig. 1: Decloux with albums on a table in the background, circa 1911; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The collection is named after its former owner, the French decorator and collector Jean Léon Decloux (1840–1929). He and his eldest brother started out with a gilding shop before he developed his expertise in 18th-century French interiors and ornamental paintings, with a particular passion for the late 18th century, known as the Louis XVI style, after the French king who reigned during this period. Although we do not know the full extent of Decloux’s collection, we do know from several sales and letters that he had a formidable collection of French decorative arts, including furniture and ceramics, as well as a very large prints and drawings collection. His ornament print collection played a particular role as source material for his work as a decorator. In fact, he specifically describes commissioning new painted motifs on 18th-century panels (boiseries) based on prints and drawings from his collection.

Fig. 2: Drawing, Male Monkey with Tambourine, 1860–90; Style of Christophe Huet (French, 1700–1759); Gouache over graphite; 31.5 × 32 cm (12 3/8 × 12 5/8 in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1911-28-76-f

Fig. 3: Bound Plate, Le Tambour de Basque, Plate 10, from Singeries ou différentes actions de la vie humaine représentées par des singes, 1743; Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Guelard (French, 1719–ca. 1755) after Christophe Huet (French, 1700–1759); Published by Francois-Philippe Charpentier (Paris, France); Etching on laid paper; 25.9 × 31.8 cm (10 3/16 × 12 ½ in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-319-21

HOW DID COOPER HEWITT COME TO OWN THE DECLOUX COLLECTION?

Sarah (1859–1930) and Eleanor (1864–1924) Hewitt[3], who founded the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now Cooper Hewitt) in 1897, first met Decloux at a luncheon in France during one of their annual trips to Europe. Decloux was charmed by the sisters’ mission to build a museum of decorative arts in the United States, and he invited them to his villa in Sèvres to see his collection. The blossoming relationship is captured in a series of letters written between 1906 and 1911 by Decloux to Eleanor that discuss the acquisition and collecting of drawings, metalwork, paneling, and jewelry along with the development and motivations behind the project to create a library of ornament and architecture prints—or “ancient works,” to borrow the term used by Decloux.

As early as August 1907, the library is described by Decloux as indispensable for a school of decorative arts, for, as he puts it, these documents are true sources of design, as important as the objects themselves. Decloux positioned himself as their agent making use of his network of collectors and dealers rather than simply buying on the Hewitts’ behalf at auctions. He advised the sisters on the fundamentals of such a library and current market values. In late 1907, Decloux sent an extensive list of foundational works that should be included in the library, stating that these represent the bare minimum for the museum’s library of decorative arts. Decloux was undoubtedly inspired by the recent publication of the Berlin Museum of Decorative Arts[4] ornament print collection, which he mentions in a letter as being under his eyes as he writes, regretting that France no longer had anything as complete as Berlin.[5]

Fig. 4: Gilt mount in the form of a quiver with arrows and a floral festoon (France), 1780; Bronze; 12.5 × 7.8 × 5.6 cm (4 15/16 × 3 1/16 × 2 3/16 in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1910-30-41

Decloux’s list titled “Composition of a Library of Works of Decorative Arts from the 17th to the 19th century” (“Composition d’une Bibliotheque d’ouvrages d’art decorative, du 17e au 19e siècle”) is broken down into periods relating to the reigns of the French kings—Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715), the Regency (1715–23), Louis XV (r. 1723–74), and Louis XVI (r. 1774–92)—with details of the prints’ availabilities, costs, and their general importance. He also makes several references to copies in his own collection and the prices he paid.

Fig. 5: Decloux letter, two pages of “Composition d’une Bibliotheque d’ouvrages d’art decorative,” undated (probably 1907); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The list includes the great inventors and purveyors of the major artistic styles of the period—baroque, rococo and neoclassicism—with prints by and after Jean Berain (1640–1711), Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695–1750), G. M. Oppenord (1672–1742), Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), Claude Gillot (1673–1722), J. A. Watteau (1684–1721), François Boucher (1703–1770), J. B. Pillement (1728–1808), J. C. Delafosse (1734–1789), G. P. Cauvet (1731–1788), and Henri Sallembier (ca. 1753–1820), just to name a few, along with major architectural volumes by D. Marot (1661–1752), G. Boffrand (1667–1754), and J. F. Blondel (1705–1775). The list reveals Decloux’s personal taste as well as his collecting habits. For example, he describes the complete works of Pierre Ranson (1736–1786) as impossible to find but “useful for painter/decorators,” and that he himself managed to acquire 400 plates in six volumes, along with eight original drawings in watercolor and gouache, subsequently acquired by the museum in 1911.

Fig. 6: Drawing, Elevation of the Wall of a Bedroom with Alcove, ca. 1780; Designed by Pierre Ranson (French, 1736–1786); Pen and brown ink, brush and gouache, black wash, graphite on white heightening paper; 28.1 × 47 cm (11 1/16 × 18 ½ in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1911-28-262

Fig. 7: Title Page and Wall Elevation, Plate 7, from II Cahier de décorations d’appartements. 1777–79; Jacques Juillet (French, 1739–1784) after Pierre Ranson (French, 1736–1786); Published by Émilie-Louise Avaulez (French, active 1777–1779); Etching and engraving on laid paper; Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-392-7

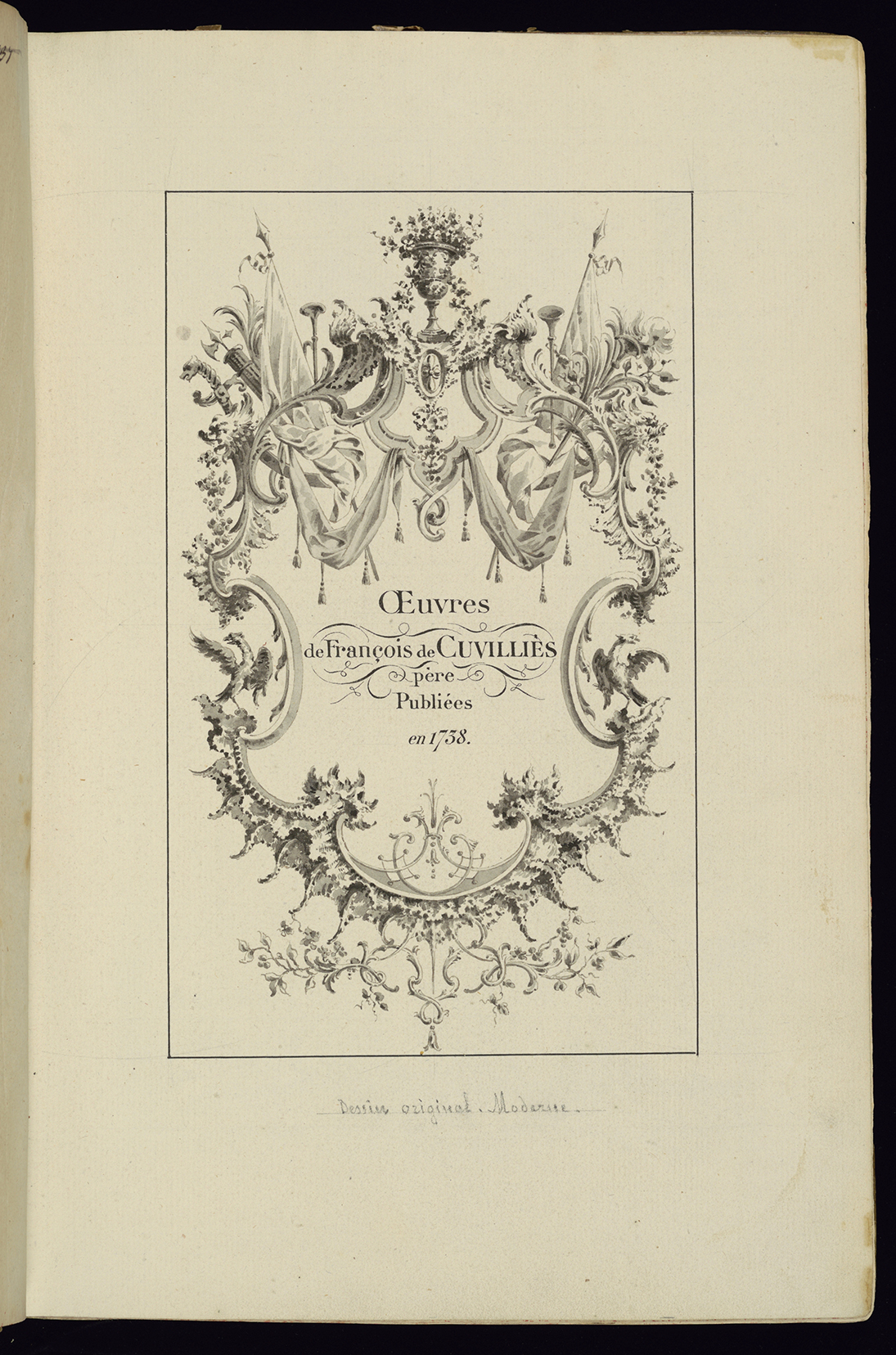

Despite Decloux’s instructional tone, the sisters were not novice print collectors. In one letter, Decloux congratulated them on their early purchases of J. B. Pillement’s rococo and particularly “chinoiserie”[6] designs, stating rather enviously how much he had to pay for them recently, emphasizing their rising costs and demand. Alongside his compliments, Decloux also attempts to entice the sisters with some of his more luxurious purchases, such as the works by Jean-François de Cuvilliés (1695–1768) and his son in an “old binding” that he has restored and in which he adds a new manuscript titlepage, along with two Oppenord albums, for a total cost of 3,800 francs. The sisters declined this first offer, but the albums were most likely part of the final 1921 purchase. The collection contains seven albums of the works by the Cuvilliés family, each with modern ornamental manuscript title pages, totaling 1,582 prints. One of these seven albums is bound in a historic 18th-century binding, but it includes fewer plates than originally mentioned by Decloux. The albums may have been reorganized and rebound once they entered the museum collection.

Fig. 8: Title Page, Œuvres de François de CUVILLIÉS père Publiées en 1738, ca. 1908; Pen, ink, brush, and wash on paper; 34.4 × 22.4 cm (13 9/16 × 8 13/16 in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-281-1

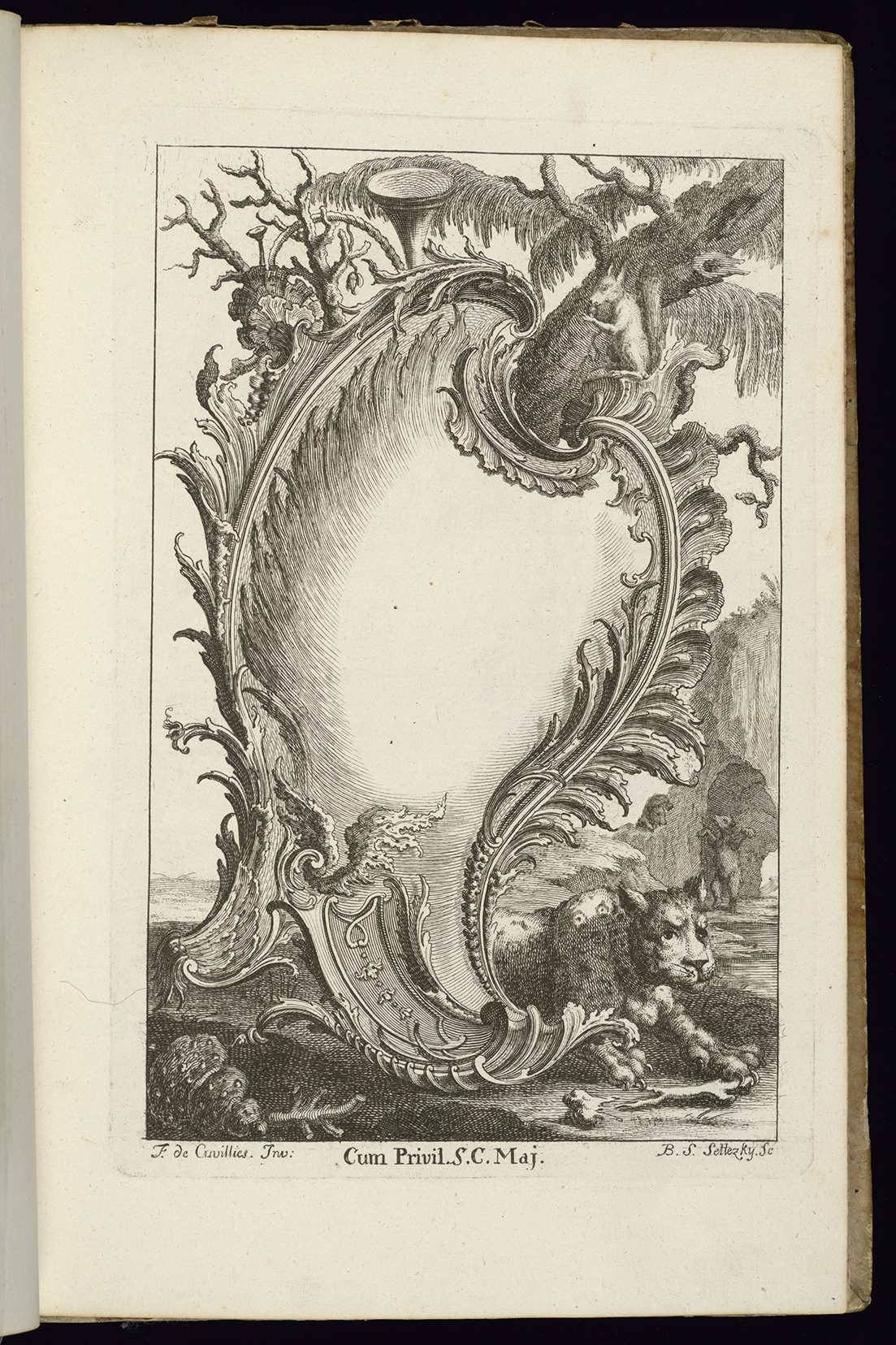

Fig. 9: Bound Print, Cartouche Design, from Livre de Cartouches Irréguliers, 1738; Balthazar Sigismond Setlezky (German, 1695–1774) after François de Cuvilliés the Elder (Belgian, 1695–1798); Published by François de Cuvilliés the Elder (Belgian, 1695–1798); Etching and engraving on paper; 28.5 × 18.9 cm (11 1/4 × 7 7/16 in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-281-37

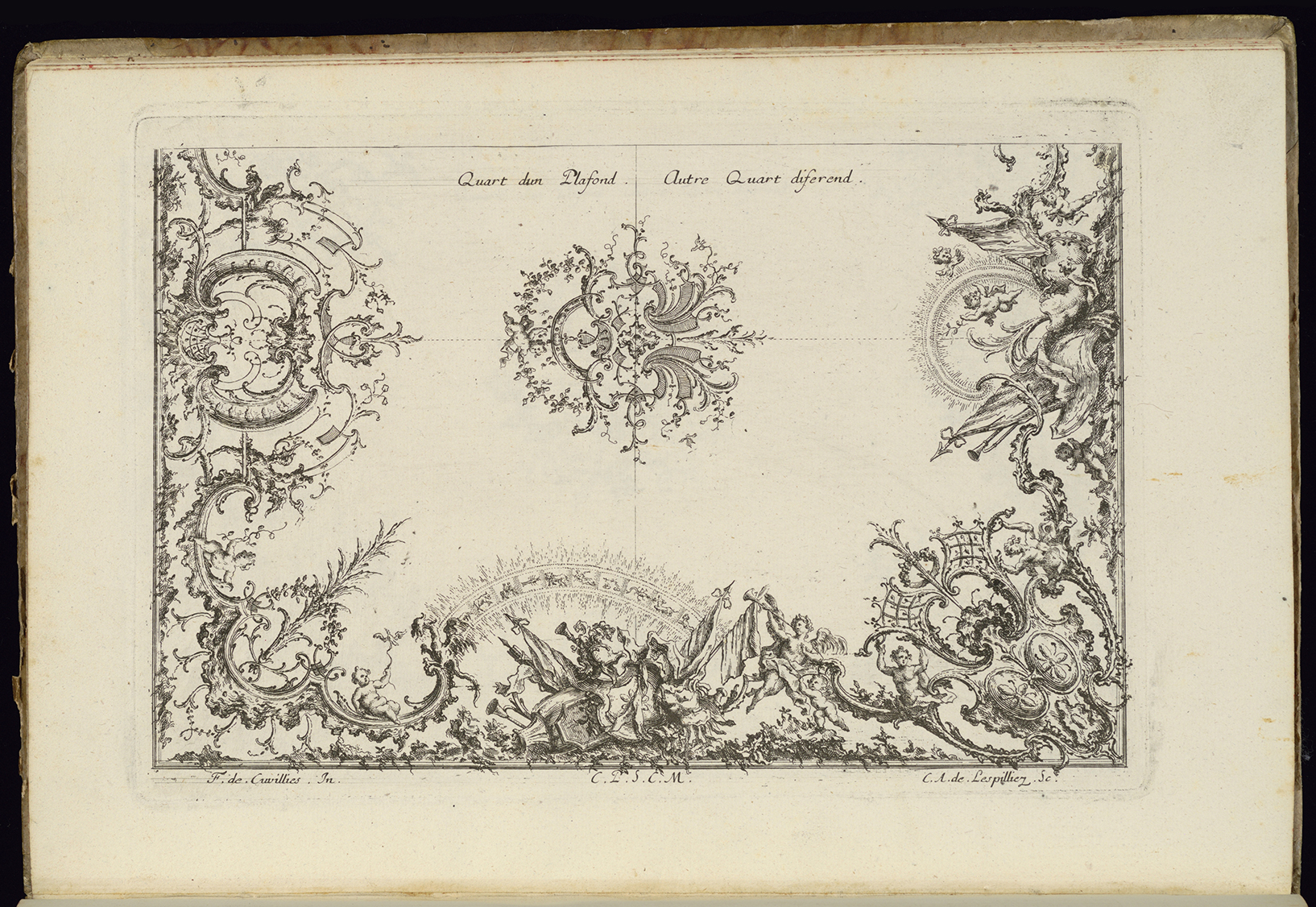

Fig. 10: Bound Print, Two Quarters of a Ceiling, from Nouveau Livre de Plafonds, 1740–68; Carl Albert von Lespilliez (German, 1695–1768) after François de Cuvilliés the Elder (Belgian, 1695–1798); Published by François de Cuvilliés the Elder (Belgian, 1695–1798); Etching and engraving on paper; Dimensions of bound volume: 18.8 × 27.7 cm (7 3/8 × 10 7/8 in.); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-281-81

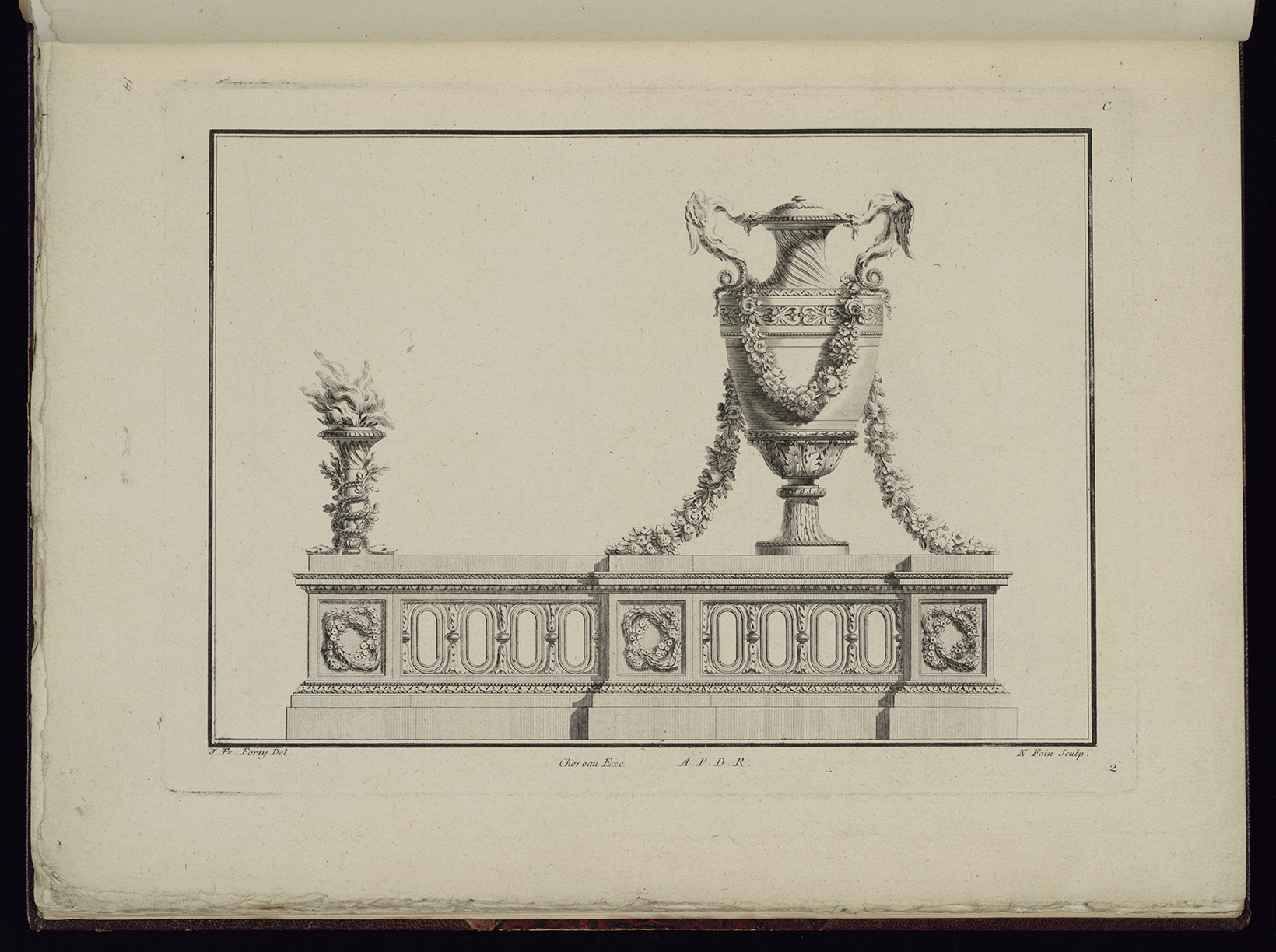

The library project began when an initial group of 16 albums of “18th-century ornaments” was sent to New York City by way of the Hewitts’ mutual friend Mrs. George T. Bliss (née Jeannette Dwight) who offered to bring the albums back with her personally from France in January 1908.[7] The shipment includes two albums of metalwork designs by Jean François Forty (1743–1800) and seven albums of furniture, vase, and trophy designs after Richard de Lallonde (active 1780–1796) for a total value of 810 francs.[8]

Fig. 11: Bound Print, Andiron (Firedog) Design, Plate 2, from Cahier de six Feux de Cheminées, à l’usage des Fondeurs, 1775–94; Augustin Nicolas Foin (French, 1726–circa 1759) after Jean François Forty (French, active 1775–1790); Published by Jacques-François Chereau (French, 1742–1794); Etching on paper; (Dimensions not recorded); Purchased for the Museum by the Advisory Council, 1921-6-310-15

In March 1908, Decloux was ready to send an additional ten series of ornament prints, and in May 1908, he received authorization from the sisters to spend 5,000 francs on prints and books of ornament, but warned them that this will not cover much once the binding and conservation costs were taken into account. Decloux never provided any details regarding the provenance of his acquisitions. He very rarely mentioned collectors (never by name) and sometimes auctions but without any details. But the library project changed shape and scale when Decloux’s nephew and only heir died suddenly. In January 1910, Decloux wrote that he now wished to sell his entire collection of books, drawings, gouaches, pastels, and paintings relating to the decorative arts to the museum, an opportunity seized by the sisters who were able to raise the money to acquire the collection and thus achieved their ambition of creating a reference library of ornament prints for the museum. A project that Decloux warned would take many years to complete was now possible due to the fortuitous relationship the Hewitts had fostered with their French collector-decorator.

Fig. 12: Students at the Cooper Union Museum sketching from the albums with prints on the walls, 1921; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Today, the Decloux digitization and cataloging project contributes to the legacy and vision of its founders by providing unprecedented access to this wondrous “Library of Decorative Art,” a truly invaluable resource illustrating the history of European design and architecture, and potentially a source of inspiration for future designers and artists.

Rachel Jacobs, Remote Senior Research Cataloger, Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design

Notes

[1] Some of the information and data relating to the prints is not yet visible on the website due to formatting issues. Please contact CooperHewittStudyCenters@si.edu to learn more about any Decloux prints online. To schedule an appointment to view any of the material, visit https://www.cooperhewitt.org/collections/studycenters/.

[2] The standard catalogs of ornament prints are D. Guilmard, Les Maîtres Ornemanistes (Paris, 1880–81) https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6122798r and the Katalog der Ornamentstitchsammlung der Staatlichen Kunstbibliothek (Berlin, 1939) https://archive.org/details/katalogderorname00staa.

[3] For more information about the Hewitt sisters and the founding of the museum, see https://www.cooperhewitt.org/design-topics/museum-history/.

[4] Peter Jessen, Katalog der ornamentstich-sammlung des Kunstgewerbe-museums (Berlin: Kunstbibliothek, 1894), https://archive.org/details/katalogderorname00staa.

[5] Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum records.

[6] Derived from the French word for “Chinese” (“Chinois”), used to describe a European style of ornament associated with rococo, inspired by Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian artistic traditions, which reached its height in popularity in the middle of the 18th century.

[7] Her daughter Susan Dwight Bliss (1882–1966) later served as a director of the Cooper Union Museum following Sarah Hewitt’s death in 1930.

[8] In 1908, a male worker in Sweden would have worked 1,593 hours to make the equivalent of 810 French francs. In 2015, a male Swedish worker would have received $39,515 for the equivalent number of hours in 1908. Another conversion is based on price of gold: 810 francs would buy 235.98 grams of gold, and the price of 235.98 grams of gold in 2015 was $8,801.12, which is about $11,597.78 today (via historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html).