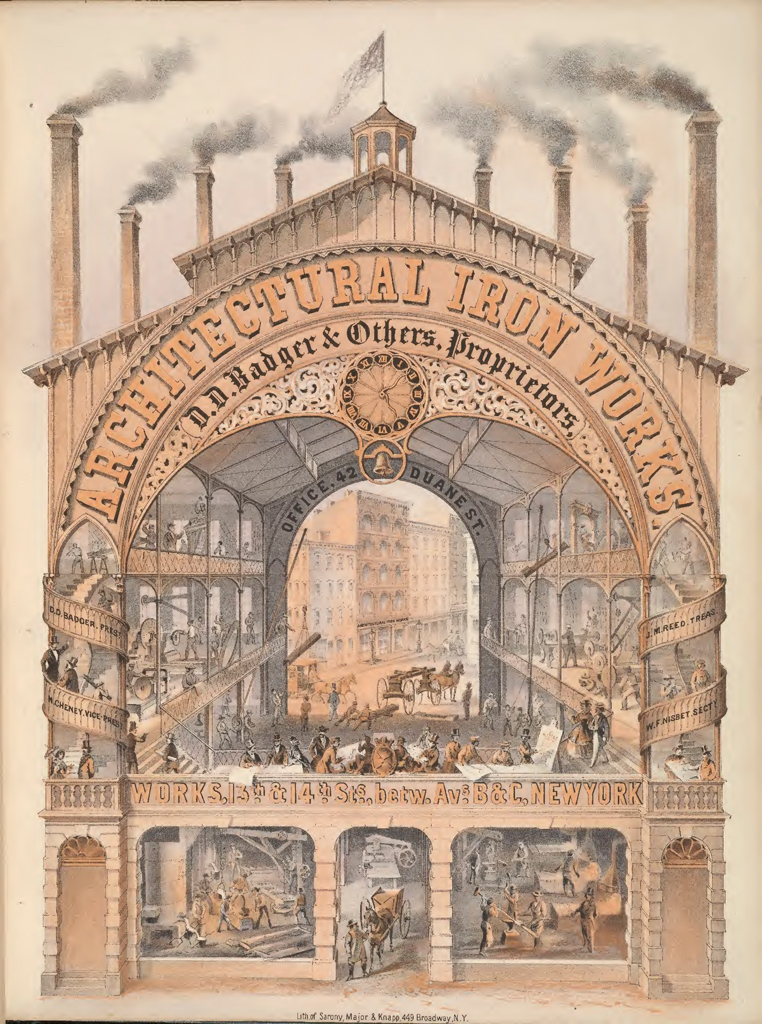

On a long ago walking tour of downtown New York, I was charmed and mystified to see people pulling refrigerator magnets or little alphabet letters out of their pockets and having them cling to the deceptively ordinary front of a building! They stuck! This is the test of a cast iron building. The Library has in its collection a rare, original copy of Daniel Badger’s 1865 “Illustrations of Iron Architecture made by The Architectural Iron Works of the City of New York.” They were a leading foundry in New York City during the 1850’s and ‘60’s, and this catalogue was produced to display buildings constructed by the company as examples of what it could manufacture for potential customers, and to demonstrate the diversity of iron architecture to architects. High-quality, monochromatically-colored lithographs depict buildings and examples of their details, such as window arches, columns, capitals and cornices.

The majority of the illustrations depict the popular cast-iron facades that were used as storefronts. Cast-iron facades were very attractive to New York business owners and architects for several reasons. They were flame-resistant; they could be assembled very quickly – the fast construction made possible by prefabricated cast-iron parts was unprecedented. The strength of cast-iron meant that it could support large windows, a real asset in workrooms before electricity and in displaying goods for sale.

The decorative elements of the facades were as attractive to customers as they were to business owners. During the Victorian era, elaborate ornament and historic revival styles were very popular, and iron facades could provide fashionable decoration at a lesser cost that hand-carved stonework.

The highest concentration of cast-iron buildings in the United States is in downtown New York City, where historic preservation efforts have saved many important buildings. A walk around the SoHo Cast Iron District demonstrates this important part of New York’s architectural history

A digital edition of the 1865 catalogue is available. Notably, the first-floor façade of the Cooper Union building on Astor Place, where this museum originated, was produced by the Architectural Iron Works, as you can see in the online edition. The decline of cast-iron architecture around the turn of the century was due to the new technology of steel construction, which allowed for taller, more cheaply constructed buildings. Though cast-iron construction influenced the development of the steel-frame skyscraper, cast-iron architecture did not evolve with twentieth-century architectural styles, and has remained a testament to the intricacies of Victorian architecture.