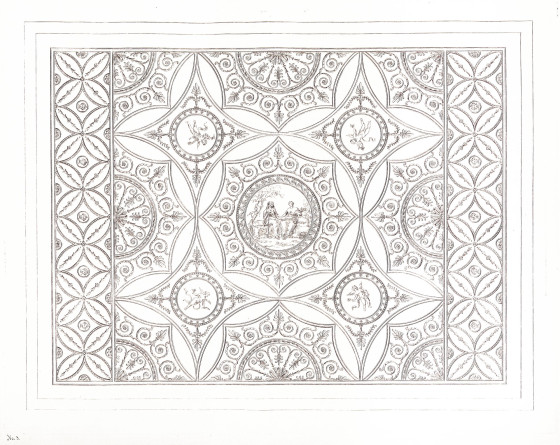

The stylistic revolution engineered by the architectural partnership of Robert (1728-1792) and James Adam (1732-1794) transformed British and Irish domestic interiors from the late 1750s to the close of the eighteenth century. Opposed to the architectonic Palladian classicism fashionable in early Georgian Britain, the Adam classical style was characterized by an eclectic and inventive use of sources, both antique and modern, and by an increasingly delicate and refined approach to composition, ornament and color. Decorated ceilings in plaster and paint were of cardinal importance to the coordinated schemes they helped pioneer. This autographed design by George Richardson (1737/8–c.1813) exemplifies a mode of decoration – customarily referred to as “Adamesque” or “Adamitic” – subsequently practiced by a generation of British architects, including James Wyatt, Henry Holland, William Thomas and Charles Cameron.

Described by architectural historian Howard Colvin as “an accomplished draughtsman and designer of internal decoration in the Adam style,” George Richardson remains a marginal figure in British architectural history yet deserves to be better known.[1] Originally apprenticed to the Adam architectural practice in Edinburgh in the mid 1750s, Richardson escorted James Adam on his grand tour to Italy in 1760–63, and was later engaged as a draftsman in Robert Adam’s office in London until 1769. Although he began exhibiting his own designs at the Society of Artists from 1765, and at the Royal Academy from 1774, Richardson is now best remembered as author and publisher of a number of architectural books, including A Book of Ceilings in the Stile of the Antique Grotesque, which was issued in installments between 1774 and 1776 and enjoyed a wide distribution throughout the British Isles. The design and content of Richardson’s Ceilings astutely combined the elegance of the folio volume, aimed at genteel architectural tastes, with something of the practical appeal (and cost) of the octavo and duodecimo builders’ handbook. It was especially influential in Ireland, where a number of designs transcribed directly from its pages may still be seen in the halls, drawing rooms and dining parlors of houses in town and country.[2]

George Richardson. A book of ceilings in the stile of the antique grotesque // composed, designed, and etched by George Richardson … London : [s.n.], 1774. Smithsonian Libraries. f NA2950 .R52 1774

Conor Lucey is an Irish Research Council postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania.

[1] Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995): 810–11.

[2] Conor Lucey, ‘British agents of the Irish Adamesque’, Architectural History, 56 (2013): 135-70.

[3] George Richardson, “To the Public,” March 22, 1774.