Darning Sampler, 1836; silk embroidery, cotton foundation; 24.1 x 23.5 cm (9 1/2 x 9 1/4 in.); Bequest of Gertrude M. Oppenheimer; 1981-28-208

MENDING TRADITIONS

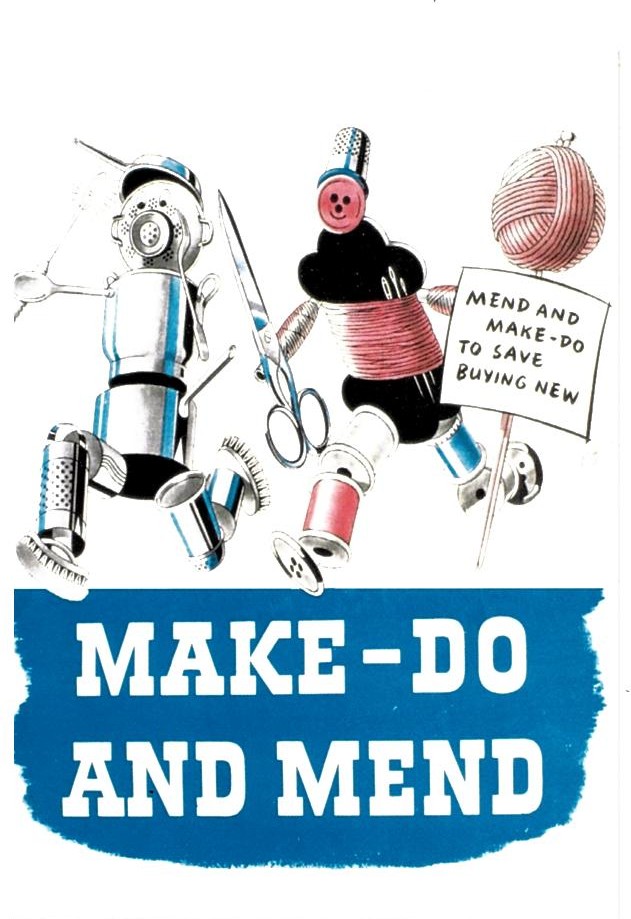

Mending used to be a widespread households practice. Linens and clothes were carefully maintained. The main motivation was economic: it was much cheaper to repair fabrics and garments than to purchase new items. Textile history is filled with compelling examples of repairs. In the eighteenth-century Great Britain and Holland, young girls learned how to mend on darning samplers. They patiently filled holes in pieces of fabric with colorful embroidered patterns that reproduced woven structures. Until the late nineteenth century, Japanese common people perfected their repair techniques with their beautiful boro patchworked garments stitched in sashiko technique. The Make Do and Mend ethos flourished in France, the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1940s. Materials rationing imposed during World War II highly impacted the apparel industry. Buying new was limited by coupons, which encouraged people -and women especially- to take good care of their personal belongings and find creative ways to make their own clothes. The Make Do and Mend message was advertised by governmental campaigns as a patriotic duty. It was promoted through numerous booklets, posters and magazines that shared tips and techniques to remain stylish, repair materials, and make old new again.[1]

How to Make-Do-and-Mend, Warwok News, British Paramount News (1943). The exhibition presented in the film was organized by the Board of Trade and took place in 1943 at Harrods, London. It exhibited remodeled garments and darning techniques to remain fashionable with “something good as new.” Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London, United Kindgom.

Promote longevity, fight disposability

Today fashion and textile items have become extremely affordable. Repairing our garments has lost its appeal for the majority of us who have given way to the sirens of fast-fashion. Why bother? The answer is ethical, but also environmental. It can play a positive role in reducing energy, raw material and water consumption. This artisanal practice may also be considered as a reaction against the throwaway culture that has become so insidiously prevalent. Repairing our damaged garments and textiles is an opportunity to rethink our relationship to our everyday objects. It may sound a daunting task, but it can be as simple as replacing a missing button, removing a stain, fixing a lining, hemming a pair of pants, or patching a hole. In Emotionally Durable Design, British sociologist Jonathan Chapman says: “Emotionally durable design explores the idea of creating a deeper, more sustainable bond between people and their material things. The ultimate aim is to reduce the consumption and waste of resources by increasing the durability of relationships between consumers and products.”[2]

Propaganda poster dating from World War II, c. 1941 © Robert Opie Collection.

It can also be a playful and creative experience. The growing mending community is very active through social media, constantly sharing new stitches, organizing workshops, and gathering in Repair Cafes. The practice has particularly regained momentum in the UK. Tom van Deijnen, Brighton-based author of the blog Tom of Holland and influential advocate for the cause, explores woolen garments’ life cycles by using traditional repair techniques. His Visible Mending Workshops enjoy great success. Van Deijnen intends to recreate “an emotional link between the wearer and garment.” Darning need no longer be invisible and discreet. This new aesthetic that mixes old and new, vintage and remodeled garments, is an answer to standardization and a source of inspiration for designers.

[1] Jennifer Farley Gordon and Colleen Hill, Sustainable Fashion, Past, Present, and Future, London: Bloomsbury, 2015, 27-30.

[2] Jonathan Chapman, Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy, Abingdon on Thames: Routledge, 2005.

About the Author

Magali An Berthon is a textile researcher and designer, focusing in particular on world textile crafts and sustainable fashion. After an MFA in textile design in Paris, she studied textile history at the Fashion Institute of Technology NY on a Fulbright fellowship in 2014. Since June 2015, she is a curatorial fellow at the Textile Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Scraps Stories

This post is part of the blog series Scraps Stories dedicated to exploring sustainable textiles and fashion, in relation to the exhibition Scraps: Fashion, Textiles, and Creative Reuse.

5 thoughts on “Make Do and Mend: The Art of Repair”

Lorrie A. Nelson on March 2, 2017 at 10:10 pm

Thank you for this informative article. As a modern needle worker who embroiders just about anything not moving, I have always seen photos of daring samplers but never with such clarity and in color. Thank you for your time and care.

Thomas Magnusson on March 3, 2017 at 1:48 am

Thank u for an informative and intresting reading!

Gordon Pradl on June 19, 2017 at 2:26 pm

An important commentary on our current disposable economy. While the information here includes the practical, it also exposes a lost aesthetic, including a lost philosophy of social living.

Randy Bazile on November 23, 2017 at 8:11 am

I love learning new things everyday! Thank you for this article!

Gail MacDonald on July 11, 2018 at 1:41 am

Do you know what the earliest example of darning is .

So far the earliest I have found is 15-16 cent piece held at V&A .

Can you do better???

Yes I am a student